(Robert Wilson, Hadrian’s Villa, c.1765: Tate)

‘At night I trailed from one window recess to another’, the Emperor Hadrian recalls in Marguerite Yourcenar’s novel, ‘from balcony to balcony through the rooms of that palace where the walls were still cracked from the earthquake, here and there tracing my astrological calculations upon the stones, and questioning the trembling stars. But it is on earth that the signs of the future have to be sought.’[1]

So it is. ‘Ghosts await you in the future if they do not follow you from the past’, Sarah Moss wrote, and: ‘No one who knows what happens in the world, what humans do to humans, has any claim to contentment.’[2] Yes. I write pages and delete them, since they serve no real purpose except to relieve my feelings for a short while. The past is not always a foreign country and they do not always do things differently there. As Pankaj Mishra said in his recent ‘Winter Lecture’: ‘It hardly seems believable, but the evidence has become overwhelming: we are witnessing some kind of collapse in the free world.’[3]

Early summer creeps on, though fitfully. Watching rose petals fall from the bush in a light wind, I remembered Pound’s Canto XIII, the first in which Confucius appears, and which ends:

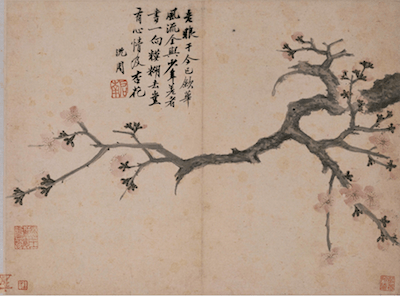

The blossoms of the apricot

blow from the east to the west

And I have tried to keep them from falling.[4]

(Shen Zhou, ‘Apricot Blossom’, leaf from the album, Dreaming of Travelling While in Bed: Palace Museum, Beijing)

Ronald Bush observed that: ‘To keep the blossoms of the apricot from falling is to keep nature in a permanent vernal bounty.’[5] It also seems to me to signify cultural contact, the free exchange of ideas, without the limits of borders or nationalism. At that stage, Pound was using Guillaume Pauthier’s translation of Confucian texts in Confucius et Mencius: les quatre livres de philosophie morale et politique de la Chine and had written in ‘Exile’s Letter’:

Intelligent men came drifting in from the sea and from the west border,

And with them, and with you especially

There was nothing at cross purpose,

And they made nothing of sea-crossing or of mountain crossing,

If only they could be of that fellowship,

And we all spoke out our hearts and minds, and without regret.[6]

On the daily walks we speak our minds but, just lately, exchanges are punctuated by information from our newly downloaded Merlin app, available from Cornell University, which draws on a huge database of bird sounds, sightings and photographs to identify what you’re probably hearing in that nearby tree or passing overhead.

So we stroll along narrow paths thus:

Politics, dinner, politics. . .

‘Blue tit. Carrion crow. Wren.’

Politics, domestic details, politics, cat, literary chuntering. . .

‘Dunnock. Blackcap. Chiffchaff.’

Ash dieback, politics, university gossip, politics. . .

‘Blackbird. Herring gull. Great tit. Jay!’

Excuse me, sir, let me just ask about the birdsong: in a world both literally and metaphorically on fire, democracies hanging by a thread, war crimes, liars and knaves in public places – does it help?

Why, yes, a little – rather more than a little, in fact. . .

Notes

[1] Marguerite Yourcenar, The Memoirs of Hadrian, translated by Grace Frick, with Yourcenar (1951; Penguin Books, 2000), 82.

[2] Sarah Moss, Signs for Lost Children (London: Granta Books, 2016), 88-89, 97.

[3] Pankaj Mishra, ‘The Shoah after Gaza’ [Winter Lecture], London Review of Books 46, 5 (7 March 2024).

[4] The Cantos of Ezra Pound, fourth collected edition (London: Faber and Faber, 1987), 60.

[5] Ronald Bush, The Genesis of Ezra Pound’s Cantos (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 251.

[6] ‘Exile’s Letter’, Ezra Pound: Poems and Translations, edited by Richard Sieburth (New York: Library of America, 2003), 255.