(George Romney, Mirth and Melancholy (Miss Wallis, Later Mrs James Campbell): National Trust, Petworth House)

‘What did you do in the end times?’ Well, among other things, I reread Olivia Manning’s Fortunes of War with immense pleasure and admiration. Here is the eunuch in the hallway of the Pomegranate nightclub in Athens: ‘His face was grey-white, matte, and very delicately lined. It was fixed in an expression of profound melancholy.’[1]

In 1915, after refraining from reading it until he had his own ‘few pages’ out of the way, Joseph Conrad wrote to the author of The Good Soldier: ‘The women are extraordinary—in the laudatory sense—and the whole “Vision” of the subject perfectly amazing. And talking of cadences, one hears all through them a tone of fretful melancholy extremely effective. Something new, this, in Your work my dear Ford – c’est très, très curieux. Et c’est très bien, très juste. You may take my word for that —speaking as an unsophisticated reader first—and as homme du métier afterwards—after reflection.’[2]

That ‘fretful melancholy’ is perhaps a distant relation of the ‘hilarious depression’ identified by Graham Greene in his review of Ford’s Provence.[3] But it’s the word ‘melancholy’ that lingers more determinedly: how could it not, in yet another news cycle dominated by the latest governmental cowardice, grubbiness and xenophobia?

‘Come to me my melancholy baby/ Cuddle up and don’t be blue’. So ran the 1912 song, ‘My Melancholy Baby’, since associated with some famous names—Judy Garland, Al Bowlly, Connie Francis, Bing Crosby. The word itself has a long history, beginning as one of the four humours in Hippocratic medicine. Black bile, linked not only to melancholy but to one of the elements, Earth, and later to the season of autumn.[4] John Keats grants melancholy goddess status, associating her with beauty and joy as well as loss: ‘Ay, in the very temple of Delight/ Veiled Melancholy has her sovran shrine’.[5] But such nuances were sternly ironed out over time and the word became, as it has essentially remained, a near-synonym for sadness, though usually implying something deeper and longer-lasting than the common or garden kind and, often, of rather mysterious or inexplicable origin.

‘This was one of the blackest days that I ever passed. I was most miserably melancholy’, the sufferer James Boswell wrote; and in a letter of the following year: ‘Yet let me remember this truth: I am subject to melancholy, and of the operations of melancholy, reason can give no account.’[6] He recalled of Dr Johnson: ‘Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, he said, was the only book that ever took him out of bed two hours sooner than he wished to rise.’[7] Robert Burton and Edward Young, author of Night Thoughts, are probably the big cheeses of British gloom. I have a copy of the Anatomy, a reprint of the 1932 edition, introduced then by Holbrook Jackson (bibliophile and journalist, who had bought the New Age in partnership with A. R. Orage), and in the New York Review Books edition by William Gass. I have, though, only sampled and dipped, rather than read cover to cover. Alexandra Harris mentioned that Burton, ‘it was rumoured, took his own life in his college room in Christ Church. If this is true, the date makes sense. He died on 25 January 1640, well past the encouraging feasts of Christmas, at a melancholy time of the year.’[8]

An understandable trajectory there: the falling off or lapsing back from good fare and company to a more customary level, and the likely worsening of weather into the bargain. Melancholy often sits companionably enough beside modifying words or notions. Robert Graves remembered an old man in an antique shop telling him that ‘everyone died of drink in Limerick except the Plymouth Brethren, who died of religious melancholia.’[9] Ernst Jünger, fighting on the Western Front, remarked: ‘How often since that first time I’ve gone up the line through dead scenery in that strange mood of melancholy exaltation!’ And he remembered walking through a neglected but flourishing landscape: ‘Nature seemed to be pleasantly intact, and yet the war had given it a suggestion of heroism and melancholy; its almost excessive blooming was even more radiant and narcotic than usual.’[10]

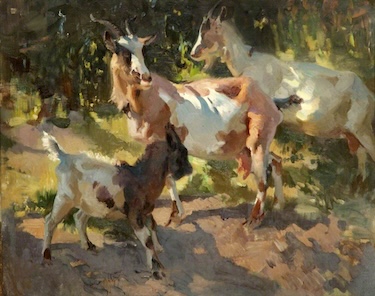

(Dorothy Adamson, Goats: Walker Gallery)

D. H. Lawrence decided that staying a long time in England made one ‘so melancholy’ but let that feeling extend to Sardinia and to other living creatures than troublesome humans: ‘Sometimes near at hand, long-haired, melancholy goats leaning sideways like tilted ships under the eaves of some scabby house. The call the house-eaves the dogs’ umbrellas. In town you see the dogs trotting close under the wall out of the wet. Here the goats lean like rock, listing inwards to the plaster wall. Why look out?’[11]

Lawrence and animals. I have a vague (and getting vaguer) memory of an exam question which I seized upon – was it writers on the animal world or specifically Lawrence? A resounding victory for the vagueness. I certainly wrote about Lawrence and, what, horses, snakes, cattle, perhaps even goats. It used to be a not uncommon ploy for people to concede cautiously that Lawrence was ‘very good with children and animals’, as though he couldn’t be trusted with anything else. Perhaps, for them, he couldn’t. Unsettling sort of chap. There are increasing numbers of unsettling figures in literary history as boundaries soften or bend. Is she modernist or not? Is he essentially Georgian or Victorian or. . .? The either/or becoming both or several or all.

Nick Jenkins, narrator of Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time, reflects of Dicky Umfraville: ‘He seemed still young, a person like oneself; and yet at the same time his appearance and manner proclaimed that he had had time to live at least a few years of his grown-up life before the outbreak of war in 1914. Once I had thought of those who had known the epoch of my own childhood as “older people”. Then I had found there existed people like Umfraville who seemed somehow to span the gap. They partook of both eras, specially forming the tone of the postwar years; much more so, indeed, than the younger people. Most of them, like Umfraville, were melancholy; perhaps from the strain of living simultaneously in two different historical periods.’[12]

Umfraville! Umfraville! – a composition for trombones or some other confident brass instruments. A bleak and almost wintry sky. ‘Cuddle up and don’t be blue’.

Notes

[1] Olivia Manning, Friends and Heroes (1965) in The Balkan Trilogy (London: Penguin Books, 1981), 802.

[2] The Collected Letters of Joseph Conrad: Volume 5 1912-1916, edited by Frederick R. Karl and Laurence Davies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 529.

[3] ‘As in his fiction he writes out of a kind of hilarious depression’: London Mercury, xxxix (December 1938), in Frank MacShane, editor, Ford Madox Ford: The Critical Heritage (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1972), 173.

[4] Roy Porter has a useful diagram of humours and elements in his The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present (London: Harper Collins, 1997), 58.

[5] John Keats, ‘Ode on Melancholy’, in The Complete Poems, edited by John Barnard, 3rd edition (London: Penguin Books, 1988), 349.

[6] Boswell’s London Journal, 1762-1763, edited by Frederick A. Pottle (London: William Heinemann, 1950), 213-214; letter to William Temple, 17 April 1764, in Boswell in Holland, 1763-1764, edited by Frederick A. Pottle (London: William Heinemann, 1952), 220.

[7] James Boswell, Life of Johnson, edited by R. W. Chapman, revised by J. D. Fleeman, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), 438.

[8] Alexandra Harris, Weatherland: Writers and Artists Under English Skies (London: Thames & Hudson, 2015), 123.

[9] Robert Graves, Good-bye to All That: An Autobiography (1929; Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2014), 349.

[10] Ernst Jünger, Storm of Steel, translated by Michael Hofmann (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2004), 9, 143.

[11] Letters of D. H. Lawrence II, June 1913-October 1916, edited by George J. Zytaruk and James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 25; Sea and Sardinia (1921), in D. H. Lawrence and Italy (London: Penguin Books, 1997), 13.

[12] Anthony Powell, The Acceptance World, in A Dance to the Music of Time: 1st Movement (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 153.