(Not a Sequoia)

‘We drove up once to the Sequoia forest’, Christopher Isherwood told W. I. Scobie, ‘and I remember Stravinsky, so tiny, looking up at this enormous giant Sequoia and standing there for a long time in meditation and then turning to me and saying: “That’s serious.”’[1]

Sometimes, even for those long-practised in weathering it, the news becomes so distressing—and the public pronouncements of senior politicians so disgusting—that it’s best to pause, assuming you’re in the luxurious position of being able to do so.

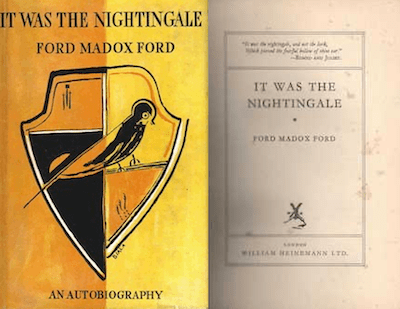

Ford Madox Ford or, let’s say, the narrator, does just that on page fifteen of It Was the Nightingale, which I’m currently reading for—let’s say the fifth time, not to sound too crazy. He pauses ‘with one foot off the kerb at the corner of the Campden Hill waterworks’. He is ‘about to cross the road. But, whilst I stood with one foot poised in air, suddenly I recognised my unfortunate position. . . .’ His rendering of the reflections that occur to him in that position appear to end, or pause, around page 88.

A few years back, I was writing about Ford and comedy, about genres and how comic writing is not viewed using the same critical criteria as ‘serious’ writing, discussing mostly the novels by Ford that might be regarded as comic: farces, satires for the most part. I was struck by a passage in a Guy Davenport essay:

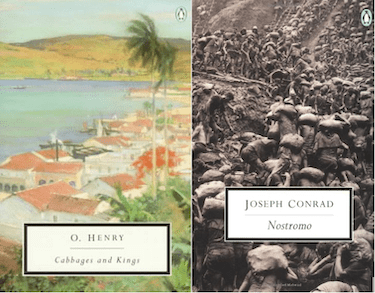

‘When Nostromo and Cabbages and Kings were published in 1904, we were beginning to make a distinction not among the four large types of literature which Northrop Frye has named comedy, romance, tragedy, and satire, or spring, summer, autumn, and winter spirits of the imagination, but between comic and serious. Some writers, like Shakespeare, Mark Twain, and Bernard Shaw, were allowed to be both at once, but with the understanding that the comic was being put in the service of the serious. The seriousness of the comic writer could only be sentimentality, and his business was to entertain, not to instruct’.[2]

Davenport writes as an admirer of O. Henry, a fat selection of whose stories he edited and introduced for Penguin Books. ‘To those friends who knew his past’, he writes there, ‘O. Henry always compared himself to Lord Jim.’ His introduction ranges over the classics—unsurprisingly, Davenport being both classicist and modernist—and some of the writers, possibly unexpected, who have admired O. Henry’s stories, among them Cesare Pavese, the Russians of the Constructivist movement, Yevgeny Zamyatin. Alluding to practitioners of the New Comedy, he remarks: ‘Miserable as our century is, we can still boast that for seventy years of it we had P. G. Wodehouse, the Menander de nos jours, and for ten years O. Henry.’[3]

Ford being one of those who was surely ‘allowed to be both at once’, I tried to convey how many comic moments—certainly passages that made me laugh—there were in the ‘serious’ books, not excluding The Good Soldier and Parade’s End.[4] I’ve wondered since whether I shouldn’t simply have said: Well, just read It Was the Nightingale. But no. It’s perfectly possible to explain, or attempt in accepted ways to do so, why you think a writer or a painter is good, what they succeed in, their distinctive personal characteristics. But explaining why someone is funny? Can it be done? You might explain why you personally find something funny but that may sound, to a reluctant or sceptical listener, as interesting and persuasive as your last night’s dream.

I quoted the estimable Frank Budgen on his friend, author of the comic masterpiece, Ulysses: ‘one day Joyce laughed and said to me: “Some people were up at our flat last night and we were talking about Irish wit and humour. And this morning my wife said to me, “[w]hat is all this about Irish wit and humour? Have we any book in the house with any of it in? I’d like to read a page or two.”’[5]

If the reader doesn’t find Ulysses funny, I suspect it’s because it feels intimidating too: this huge book, full of words, phrases, constructions, comparisons, images and symbols that you’re never come across before. Not, anyway, in those contexts and those combinations. Worse, it’s the Greatest Novel of the century or one that defined an era or the justification for the whole modern movement or—but is it funny? Well, yes, probably not if you go through it on tiptoe or hands and knees, peering warily about you as you go. But if you can relax, telling yourself that you’ll come back to it with a pick and shovel at some later date but just not now – pour a glass (leave the bottle) and sit back in that comfortable chair – things may go better.

I linger over that phrase—‘things may go better’—just for a moment, you understand. How could I not?

Notes

[1] Writers at Work. The Paris Review Interviews: 4th Series, edited by George Plimpton (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1977), 232.

[2] ‘The Artist as Critic’, in Every Force Evolves a Form (Berkeley: North Point Press, 1987), 79.

[3] ‘Introduction’ to O. Henry, Selected Stories (New York: Penguin Books, 1993), xi, xv. Possible additions to these inheritors of the New Comedy are ‘the exotic and manic S. J. Perelman and the gentle, whimsical Thurber’.

[4] ‘Ford and Comedy’, Sara Haslam, Laura Colombino and Seamus O’Malley, editors, The Routledge Research Companion to Ford Madox Ford (London: Routledge, 2019), 427-440.

[5] Frank Budgen, James Joyce and the Making of ‘Ulysses’ and other writings, enlarged edition (1934; London: Oxford University Press, 1972), 38.