(Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Spring: J. Paul Getty Museum)

Mayday, m’aider. I think, without counting pages to an absurd degree, that 1 May, along with 1 January, is only exceeded by 25 December in the extent of its coverage in The Oxford Companion to the Year, which mentions at the outset the sacrifice of a pregnant sow by the priest of Vulcan to Maia (a goddess of growth).[1] My ageing dictionary offers for Mayday ‘given to sports and to socialist and labour demonstrations’. There was such a time, I think, and the change has not been for the better. This particular Mayday, we have continuing wars and war crimes, failing states, thuggish cops violently assaulting and arresting students and faculty on several American campuses.

But here – we have local elections! Yes, one-sixth of England’s district, borough and unitary councils will hold elections tomorrow, Thursday, 2 May: 2,636 council seats to be contested in the 107 (out of 317) scheduled council elections and 48 by-elections, plus elections for 10 metro mayors, as well as police commissioners and members of the London Assembly. Our ward is in one of the 107: two councillors to be elected and the only candidates standing who contested it that last time around are the incumbents, both Green Party councillors.

We’ve been constantly reminded, of course, that this is the Year of Elections. More than 60 countries and directly affecting almost half of the world’s population. From India and the United States to Indonesia, Mexico, Iceland and Sri Lanka. It would be pleasant to view the prospect positively or even with equanimity, but it’s just too much of a stretch. Many of the countries going to the polls are not even democracies in any meaningful sense. Not that democracy is a perfect political system—if it were, there would be fewer psychopathic thugs, undisguised crooks and congenital liars in positions of power—it’s just that all the other systems are worse.

In the UK, we expect a General Election too and, around the country, people—especially those who follow politics closely—are able to indulge in the parlour game that consists of trying to identify a single sector or section of British social, cultural and economic life that the present government, in its fourteen-year tenure, has not destroyed, diminished, degraded or damaged beyond repair or recovery. Among the candidates are the health service, universities, schools, rivers and coastal waters, housing, freedom of speech, crime, social care, railways, roads, parks, the tax system, the legal profession, pedestrian thoroughfares, prisons, immigration, foreign policy, poverty, doctors, dentists, childcare, homelessness, domestic violence, the rental sector, defence, the climate emergency, the right to protest, sexual harassment in and out of the House of Commons. Answers on a polling card, please. . .

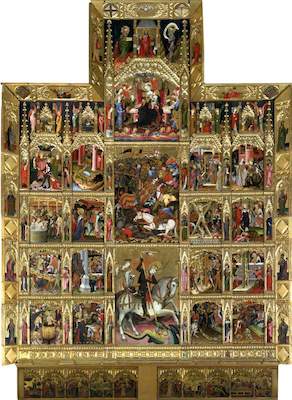

(Altarpiece of St George, Attributed to Andrés Marçal de Sas, active 1393–c.1410: Victoria and Albert Museum)

Still, as Sarah Churchwell, observed, a few years back: ‘Because most people spend little time analysing political events or studying history, democracy will always risk being shaped by voters’ feelings rather than analysis.’[2] A risk, yes, but there are points in any country’s history when the two converge, in some species of agreement: informed analysis of the last decade and a half in the United Kingdom will identify decline, dissension, worsening social and economic conditions for the majority of its citizens, while a wide-ranging survey of voters’ feelings will find an immense tiredness, if not exhaustion, in a nation where everything now is broken and nothing works – unless, as ever, you are filthy rich.

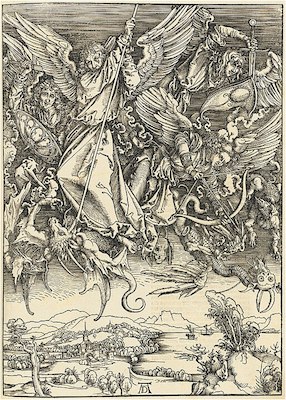

(Albrecht Dürer, St Michael Fighting the Dragon)

Churchwell wrote in another book that: ‘Mythical histories lay the groundwork for fascist politics.’[3] Also true, increasingly evident in many countries around the world, including some of the most vaunted ‘democracies’, a few of them uncomfortably close. It was briefly illuminated (through a glass, darkly) by some of the clamorous noise around 23 April, St George’s Day, the patron saint of England, though ‘very little is known of him and his very existence is often doubted’.[4] If he did exist, he may have been born in Cappadocia, may have died in Palestine and never came near England. Still, he’s the patron saint of at least fifteen countries, states and major cities around the world. And, of course, there’s the matter of that dragon, a story added centuries later. Something may have happened somewhere in Libya, it seems.

‘Before Dürer’, Philip Hoare wrote, ‘dragons existed; after him, they did not. We were left with only the dragons of our unconscious, as Carl Jung would say.’[5] Even more on topic, one might say, is Nicolas Mosley’s comment about his father, Oswald Mosley: ‘But heroes continue not to see the dragons that are in themselves.’[6]

While the local elections may not accurately predict the winners in the various constituencies in the coming General Election, they will, I think, correctly identify the losers.

Notes

[1] Bonnie Blackburn and Leofranc Holford-Strevens, The Oxford Companion to the Year (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 183.

[2] Behold, America: A History of America First and the American Dream (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018), 215.

[3] The Wrath to Come: Gone With the Wind and the Lies America Tells (London: Head of Zeus, 2022), 352.

[4] The Oxford Companion to the Year, 166.

[5] Philip Hoare, Albert & the Whale (London: 4th Estate, 2021), 11.

[6] Nicholas Mosley, Rules of the Game; Beyond the Pale: Memoirs of Sir Oswald Mosley and Family (London: Pimlico, 1994), 116.

The news of your poll results trickle into the New York Times. It looks like the results will amount to an inspiring reconstructionary tale in the political realm. Might you be superstitiously evading confident prediction, lest you jinx national hopes? Alas, here in the U.S. the bad luck runs all too deep…and the Constitution begins to look like an outmoded superstition.

Many thanks, as ever, for your March and April posts. Conrad, Kipling, and Pound–those ancient lights–remain heartening touchstones. I wish they can remain so for the future, but I begin to think they will be forgotten, condemned politically once and for all. How such condemnation could be applied to Under Western Eyes, or Nostromo, or The Secret Agent, I don’t know.

With best wishes,

Robert Caserio

LikeLike

Thank you, Robert. Good to hear from you, as always. After 2016, particularly, I’m wary of predicting any election outcome at all but this latest round seems a little more hopeful. The US, rather less so. As to the future of the literary past, yes, I suspect it will look very odd indeed, with some truly puzzling and damaging gaps. All best, Paul

LikeLike

Thanks, Paul. Good luck to the next round of results. Your reflections help one to go on.

Robert

LikeLike