(Jan Josef Horemans the Younger, A Merry Party: Hackney Museum)

‘For Books are not absolutely dead things, but doe contain a potencie of life in them to be as active as that soule was whose progeny they are; nay they do preserve as in a violl the purest efficacie and extraction of that living intellect that bred them. I know they are as lively, and as vigorously productive, as those fabulous Dragons teeth; and being sown up and down, may chance to spring up armed men.’—John Milton, Areopagitica

How was it for you?

Bad. How could it not be? Our cat died.

And—more broadly?

Some good connections, some good work done, some good books read.

More broadly still?

Pretty bad. The end of all rules-based international order. Genocidal violence, unchecked. Countries losing their minds, wars waged on children in the modern fashion. The usual stupidity, greed, aggression, corruption. Electorates incapable of paying attention. Cyclists on footpaths; cars on the pavement. Dante knew where to put those people. . .

And next year?

Ah well.

Better or—?

Ah well.

Give me a word.

Attention.

Give me a number.

Two. Three with a cat.

Give me a blessing.

May you always be threefold, even if alone.

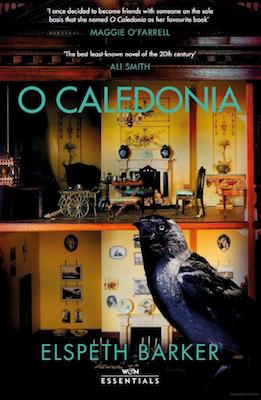

I read a lot of books this year and see that just over half of them were by women (which I find significant primarily by virtue of its non-significance now), despite Fords, Simenons, Herrons and the like. Hmm. A recent one was Charlotte Wood’s novel, Stone Yard Devotional, which I’d say is about acceptance and forgiveness, of oneself and of others—and of those who die or disappear before forgiving or being forgiven. That in itself reminds me of another novel recently read, the reissue of Elspeth Barker’s O Caledonia: ‘It was Janet’s view that forgetting was the only possible way of forgiving. She did not believe in forgiveness; the word had no meaning.’[1]

Leaning towards Janet – but here’s Willie:

MY SELF:

I am content to follow to its source,

Every event in action or in thought;

Measure the lot; forgive myself the lot!

When such as I cast out remorse

So great a sweetness flows into the breast

We must laugh and we must sing,

We are blest by everything,

Everything we look upon is blest.[2]

Ali Smith was also a little more, ah, yielding than Elspeth’s Janet: ‘many things get forgiven in the course of a life : nothing is finished or unchangeable except death and even death will bend a little if what you tell of it is told right’.[3]

Would I be that forgiving were I a victim of the numberless war crimes, sexual assaults, racist attacks, domestic outrages? Frankly, no. But we are at year’s end and, by the sound of it—bears of little brain letting off fireworks as though it were that day in November—it’s an evening of celebration.

Here’s the laureate of cheerfulness, J. G. Ballard: ‘It is a misreading to assume that because my work is populated by abandoned hotels, drained swimming pools, empty nightclubs, deserted airfields and the like, I am celebrating the run-down of a previous psychological and social order. I am not. What I am interested in doing is using these materials as the building blocks of a new order.’[4]

The eminent literary critic Frank Kermode did get to the celebratory stage but seemed to find the steps to it a little surprising. At Liverpool University, he was taught Latin by F. W. Wallbank, J. F. Mountford ‘and, rather surprisingly, George Painter’ (the celebrated biographer of Marcel Proust). ‘I took up Italian, under the instruction, also surprisingly, of the future father of Marianne Faithfull. Indeed, I drank wine in celebration of his wedding and continue to take comfort from this connection with true fame.’[5]

(Édouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (The Courtauld: Samuel Courtauld Trust)

We are rather more low-key here. A bottle of champagne, some rye bread with smoked salmon, and sitting in front of University Challenge, lamenting (that is, me lamenting) the fact that, while the contestants can answer obscure questions about astronomical phenomena, Third World flags or physiological irregularities, they are all at sea with literary questions that I vaguely assumed to be common knowledge even among household pets.

‘New Year’s Day, for us, is All Souls’ Day’, the Goncourt brothers wrote, 1 January 1862. ‘Our hearts grow chill and count those who are gone’.[6] Ah, well and ah, well. Best wishes to all, wherever you may be, and may 2025 lean more towards Life than the other thing. . .

Notes

[1] Elsbeth Barker, O Caledonia (1991; Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2021), 116.

[2] W. B. Yeats, ‘A Dialogue of Self and Soul’, Collected Poems, second edition (London: Macmillan, 1950), 142.

[3] Ali Smith, How to be both (London: Hamish Hamilton, 2014), 95.

[4] J. G. Ballard, interview with Peter Rǿnnov-Jessen (1984), cited by John Gray, ‘Crash and Burn’, New Statesman (5-11 October 2012), 52.

[5] Frank Kermode, Not Entitled: A Memoir (London: Harper Collins, 1996), 78.

[6] Edmund and Jules de Goncourt, Pages From the Goncourt Journal, edited and translated by Robert Baldick (New York: New York Review Books, 2006), 66.