And every tree is a tree of branches

And every wood is a wood of trees growing

And what has been contributes to what is.

So I am glad to have known them,

The people or events apparently withdrawn;

The world is round and there is always dawn

Undeniably somewhere.[1]

Some days, if you’re early enough, you can walk all the way round a huge Victorian cemetery and not see even a single dogwalker—though you might catch sight of a fox, if you’re lucky. The blackberries have got ahead of themselves to such an extent that they’ll barely last the month: but once in the freezer drawer, they’ll see us well into winter. Cow parsley, Anthriscus sylvestris, or Queen Anne’s lace (or, I gather, keck) still hangs on in places. A mistle thrush and a song thrush seem to answer one another and there’s a goldcrest somewhere near.

We are well past midsummer now. Glastonbury Festival is over (I shall probably get The Cure’s ‘Friday I’m in Love’ out of my head soon), the Wimbledon tennis tournament finished, the Bristol Harbour Festival has happened and the Balloon Fiesta is just a couple of weeks away. The wider canvas still largely features arterial blood and heavy boots on infant faces though even some Western politicians have now begun to wonder if deliberately starving thousands of innocent civilians and then shooting them down in cold blood day after day when they try to secure food might be just a bit over the top. Even so, to demonstrate that they know what’s terrorism and what isn’t, our government is prosecuting people who object to their country’s complicity in war crimes.

But pass on, pass on. Books, music, food, wine, love, cats.

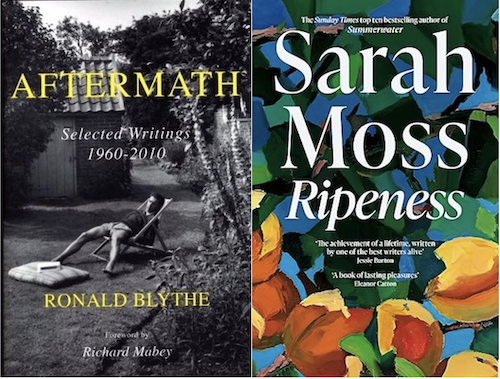

When I surface from Ford’s letters, I have waiting for me Paul Willetts’ remarkable reconstruction of the life of Julian Maclaren-Ross, Ronald Blythe, Sarah Moss, early Ernest Hemingway. Otherwise, I just revel in Anne Carson:

‘My mother forbad us to walk backwards. That is how the dead walk, she would say. Where did she get this idea? Perhaps from a bad translation. The dead, after all, do not walk backwards but they do walk behind us. They have no lungs and cannot call out but would love for us to turn around. They are victims of love, many of them.’[2]

Yes. Meanwhile, the weather, or much of it, prompts me to recognise my increasing intolerance to higher temperatures (and to much else: I know I’m widely assumed to become more conservative politically as I age but something’s clearly gone wrong). Earlier walks, more water, more cursing – I know all the tricks.

As to cats – yes, I like to remember that ‘Balthus painted himself once as a cat dining on fish, and once as the King of the Cats.’[3] Sylvia Townsend Warner mentioned, in a letter to William Maxwell (9 April 1952) , the northern Scottish traveller’s tale of seeing the cat funeral. ‘And the cat of the house, lying on the hearth, started up at these words, and exclaimed, “Then I am the King of the Cats”, and vanished up the chimney.’[4] When Swinburne died in 1909, William Butler Yeats said to his sister Lily, ‘Now I am king of the cats.’[5]

(John Butler Yeats, portrait of embroiderer, and co-founder (with her sister Lolly) of Cuala Industries, Susan Mary (Lily) Yeats (1901): National Gallery of Ireland)

The novelist, suffragist and partner—for several fraught years—of Ford Madox Ford had a good many of them: ‘Violet’s parrots—part of a menagerie that included an owl (named Anne Veronica after Wells’s novel), a bulldog and nine Persian cats—shrieked “Ezra! Ezra!” whenever they saw him bouncing up the walk.’[6]

I can, alas, only half-agree with Lord Peter Wimsey when he says to Parker at the end of that bell-ringing mystery, The Nine Tailors, ‘“Bells are like cats and mirrors – they’re always queer, and it doesn’t do to think too much about them.”’[7] Queer they may be but I think about them a good deal and seem none the worse for it.

There was a collection of essays published ‘on the Occasion of the 25th Anniversary of Finnegans Wake’, which included pieces by Padraic Colum, Frank Budgen, Vivian Mercier, Fritz Senn, A. Walton Litz and other distinguished Joyceans. It was called Twelve and a Tilly.[8]

For ‘tilly’, my Shorter Oxford has: ‘In Ireland and places of Irish settlement, an additional article or amount unpaid for by the purchaser as a gift from the vendor.’ Joyce’s nocturnal masterpiece offers four occurrences and the splendid online glossary – http://finwake.com – adds to ‘the thirteenth of a baker’s dozen’ the derivation from Irish tuilleadh, added measure.

Opening my eyes to uncertain light, I can hear the table-tennis ball moving in the kitchen and the hall, knocking against skirting-boards and doorframes. I get up for a pee and a small grey tabby runs in to check on my progress and brush against my legs. Getting back into bed, I see that it’s 03:50. Moments later, the table-tennis ball is on the move again.

Yes, we have our own Tilly now, not an added measure but one-half of a pair. Her brother is named Max, which I like in part because it was the name of the very first pet I remember, in Gillingham, Kent, a black cocker spaniel—but also because of the occasional fleeting uncertainty which attends such phrases as ‘I said to Max’ or, more plausibly, ‘I asked Max’, which might conceivably be a reference to either a handsome tabby or our leading Ford Madox Ford scholar.

Scholars, though, at least as a general rule, do not sit in the kitchen sink, talk to toy mice or suck their tails. . .

Notes

[1] Louis MacNeice, ‘Autumn Journal: XXI’, Collected Poems, edited by Peter McDonald (London: Faber, 2007), 153.

[2] Anne Carson, ‘On Walking Backwards’, Plainwater: Essays and Poetry (New York: Vintage, 2000), 36.

[3] Guy Davenport, A Balthus Notebook (New York: Norton, 1989), 7. Le Roi des Chats (1935). Balthus identified strongly with cats: in the year of this self-portrait, he began signing his letters to his future wife Antoinette as ‘King of Cats’. ‘Jeune fille’ occurs many times in the titles of his paintings—but so does ‘chat’ (sometimes together).

[4] Sylvia Townsend Warner, Letters, edited by William Maxwell (London: Chatto & Windus, 1982), 133.

[5] Yeats to Susan Mary (‘Lily’) Yeats, 12 Apr. 1909: R. F. Foster, W. B. Yeats: A Life. I: The Apprentice Mage: 1865–1914 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 616n.69.

[6] Pound, of course. Barbara Belford, Violet: The Story of the Irrepressible Violet Hunt and her Circle of Lovers and Friends—Ford Madox Ford, H. G. Wells, Somerset Maugham, and Henry James (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990), 166-7.

[7] Dorothy L. Sayers, The Nine Tailors (1934; with an introduction by Elizabeth George, London: New English Library, 2003), 305.

[8] Twelve and a Tilly: Essays on the Occasion of the 25th Anniversary of Finnegans Wake, edited by Jack P. Dalton and Clive Hart (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1965).