Re-reading an early Ford Madox Ford work recently, I noticed that, while my scrappy and often baffling notes from the previous reading ran to little more than a page, I now have something over ten pages of extracts, cross-references and occasionally more general comments. Should I be impressed or anxious? Was it admirably thorough or mildly deranged? Clearly, this reader had changed substantially in the intervening period and, to that extent, the book itself was changed. Curious, since it had seemed stable enough in its hard covers, more than a century old.

Yet – how stable, exactly, even at the most basic level? It was written by Ford Madox Hueffer, who would subsequently become (in 1919) Ford Madox Ford, in collaboration with Joseph Conrad, who had become a British subject in 1886 and was previously known as Konrad Korzeniowski. It was written when work on their initial collaborative venture, Romance, was already well-advanced but was completed and published first; an unsteady hybrid of science fiction, political satire and roman à clef, it concerned itself with nefarious dealings in a country—‘Greenland’—which was clearly in Africa and, pretty obviously, the Congo Free State of the rapacious King Leopold II of Belgium. As Ford recalled it more than twenty years later: ‘The novel was to be a political work, rather allegorically backing Mr Balfour in the then Government; the villain was to be Joseph Chamberlain who had made the [Boer] war.’[1]

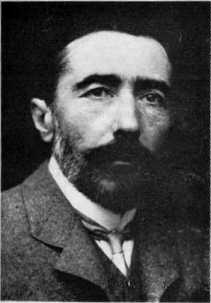

(Joseph Conrad, 1904)

Stability. A key word for those that have followed, with bafflement or appalled disbelief, the mad pantomime of British politics over the past few months. In The Inheritors, we find: ‘I became conscious that I wanted to return to England, wanted it very much, wanted to be out of this; to get somewhere where there was stability and things that one could understand.’[2] Cue a pained smile. ‘Permanence? Stability? I can’t believe it’s gone’, a later Ford narrator lamented.[3] Of course, it was—it is—always already gone. . .

In any case, I find it an intriguing and curious business, this revisiting—of a place, a person, a painting, a book, a film, a piece of music—and finding it so changed. It’s commonplace and banal, yet enduringly mysterious and fascinating. There are, to be sure, many thousands of pages of philosophy, psychology, biology, neurology, physics, optics and more, devoted to just this phenomenon. We’re increasingly comfortable with the idea that the observer alters what is observed, that the slightest shift in position or perspective alters the thing seen. Some of us saw the intriguing 1974 Alan Pakula political thriller, The Parallax View, with Warren Beatty and Paula Prentiss, and looked up the meaning of the title. (‘Parallax, you see. Observed from different angles, Gestalts alter.’)[4] Fifty years before that, in 1923, Wallace Stevens published ‘Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird’.

II

I was of three minds,

Like a tree

In which there are three blackbirds.

XII

The river is moving.

The blackbird must be flying. [5]

A goodly proportion of those thousands of pages, though, can probably be reduced to just two words of the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus, panta rei, everything flows, flux and change as the essential characteristics of the world.[6]

T. S. Eliot used two quotations from Heraclitus to preface Four Quartets, the second of them translated as ‘The way up and the way down are one and the same’. Eliot wrote of being ‘much influenced’ by Heraclitus when younger and thought the influence a permanent one. The quotations were, he said, ‘a tribute to my debt to this great philosopher.’[7]

In Little Gidding, the last of the Quartets, Eliot wrote:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.[8]

See it again but know it for the first time.

Stanley Spencer wrote of his celebrated painting, The Resurrection in Cookham Churchyard: ‘The resurrection is meant to indicate the passing of the state of non-realization of the possibilities of heaven in this life to the sudden awakening to the fact. This is what is inspiring the people as they resurrect, namely the new meaning they find in what they had seen before.’[9]

(Stanley Spencer, The Resurrection in Cookham Churchyard, 1924-1927, © Tate Gallery)

That ‘awakening’ is, again, indissolubly linked to the familiar or, at least, to that which has been seen before. Much of Spencer’s art is ‘religious’ but very idiosyncratically so, ‘visionary’ rather, an art constantly linking back to his feelings about the village of Cookham and its people, his childhood and familial memories and sensations revisited, recaptured and reworked.

Time slips and eddies. We return, retrace, revisit and see again, in thought, in dreams, in conversation. Memories lose their edges, become indistinct, bleed into others. We can’t always predict what has taken root in the mind or the nerves, what doesn’t need to be consciously recovered, what can be held and turned in a glancing light and mysteriously made new.

I could not draw a map of it, this road,

Nor say with certainty how many times

It doubles on itself before it climbs

Clear of the ascent. And yet I know

Each bend and vista and could not mistake

The recognition, the recurrences

As they occur, nor where. So my forgetting

Brings back the track of what was always there

As new as a discovery.[10]

References

[1] Ford Madox Ford, Joseph Conrad: A Personal Remembrance (London: Duckworth, 1924), 133.

[2] Ford Madox Ford and Joseph Conrad, The Inheritors: An Extravagant Story (1901; Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1999), 106.

[3] Ford Madox Ford, The Good Soldier: A Tale of Passion (1915; edited by Max Saunders, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 13.

[4] Hugh Kenner, ‘Joyce on the Continent’, in Mazes (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995), 114.

[5] Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems (New York: Vintage Books, 1982), 92, 94.

[6] ‘All things are a flowing,/ Sage Heracleitus says’, Ezra Pound wrote, adding: ‘But a tawdry cheapness/ Shall outlast our days.’ See Hugh Selwyn Mauberley, in Personae: The Shorter Poems of Ezra Pound, edited by Lea Baechler and A. Walton Litz (New York: New Directions, 1990), 186.

[7] The Poems of T. S. Eliot. Volume I: Collected and Uncollected Poems, edited by Christopher Ricks and Jim McCue (London: Faber & Faber, 2015), 907. John Fowles offers: ‘The road up and the road down are the same road’, in The Aristos (London: Pan Books, 1968), the ‘original impulse’ for the book and ‘many of the ideas’ in it having come from Heraclitus (214).

[8] The Poems of T. S. Eliot. Volume I, 208. Another faint connection for John Fowles readers: this is the first marked passage in the poetry anthology which Nicholas Urfe finds on the beach, in The Magus (London: Pan Books, 1968), 60.

[9] Kenneth Pople, Stanley Spencer: A Biography (London: Harper Collins, 1991), 226, citing the Spencer collection in the Tate Archives, reference TA 733.3.1.

[10] Charles Tomlinson, ‘The Return’, New Collected Poems (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2009), 413.