(Samuel Bough, Cricket Match at Edenside, Carlisle: Tulle House Museum and Art Gallery)

September. Autumn at last; and an end to the nonsense of summer, the increasingly anachronistic expectation of pleasant weather, an expectation mistreated by endless rain or unbearable heat. And, on Samuel Johnson’s birthday, a revisiting of his remark to Doctor Brocklesby (as refracted through James Boswell): ‘The weather indeed is not benign; but how low is he sunk whose strength depends upon the weather!’[1]

On another day, though white clouds are piled so high as to be on the point of toppling over onto the crowns of trees, they’re surrounded by sky so blue that one suspects a gargantuan deception. Still, disposable barbecues, spawned by the Devil, are nowhere to be seen and the grass of the park has been mown again, which always imparts a faint whiff of paradise.

Le paradis n’est pas artificiel,

l’enfer non plus.

Ezra Pound at Pisa, with hell very much on his mind.[2] ‘I am now the proud possessor of a Johnson’s Dictionary’, Guy Davenport announced to Hugh Kenner in 1967. ‘Dorothy [Pound] once told me EP has never owned any other, and sure enough, practically every word of H[ugh]S[elwyn]M[auberley] is used with Johnson’s rhetorical colouring (juridical, adjunct, phantasm, factitious).’[3]

Walking is more comfortable in the cooler weather, thinking also. And the near-neighbours, we dare to believe, are gone, their riotous tenancy ended. The next lot may, of course, be anything from a heavy metal band that just loves to rehearse to a group of trainee Trappists. We await with interest. So the mood swings between, say, states represented by quotations, the first something like Clare Leighton’s: ‘Who can resist the Lincolnshire name for the wild pansy: meet-her-in-the-entry-kiss-her-in-the-buttery?’ Well, not me, obviously. On the other hand, there is always the reliable standby from D. H. Lawrence’s letter to E. M. Forster: ‘I am in a black fury with the world, as usual.’[4]

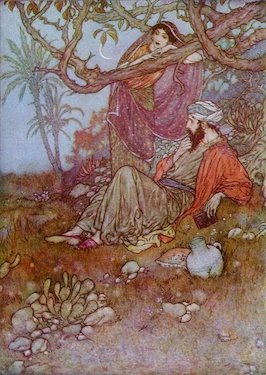

There are diversions, of course, of the usual kind, usual at this kitchen table anyway (between meals). In the ‘Credits’ section of Bad Actors, after the usual acknowledgements (publishers, agents, all those involved in the TV series of Slow Horses), Mick Herron recalls an email from a reader informing him that a line he’d used in Slough House was ‘more or less from a Robert Frost poem’. Herron asked for ‘many dozens of similar offences to be taken into consideration.’[5] And it’s true that one of the many pleasures of reading his books is picking up echoes, half-echoes, perhaps-echoes from poets and novelists. Some might not stand up in court—courts vary, as is painfully clear by now, I suspect—but I’m pretty sure about this from the third Zoë Boehm book, Why We Die: ‘Life was too short to approach death head-on. On that journey you took any diversion available – marriage, travel, children, alcohol. At the very least, you stopped to admire the view.’[6] Beside which I would set the resonant advice from William Carlos Williams, to ‘approach death at a walk, take in all the scenery.’[7] Elsewhere, Margery Allingham’s detective, Albert Campion, remarks to Guffy Randall: ‘“Across the face of the East Suffolk Courier and Hadleigh Argus, Fate’s moving finger writes, and not very grammatically either”.’[8] The response of the many readers of Edward Fitzgerald’s rendering of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám is surely to nod sagely at a clear or misty memory of stanza LI:

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.[9]

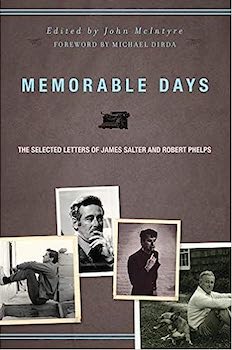

(A jug of wine, a loaf of bread and Edmund Dulac)

Or again, thirteen pages earlier, Campion talking of the intention to wait for an offer of purchase ‘and then to freeze on to the vendor with the tenacity of bull-pups.’ Bull-pups? Freezing? Here is Sherlock Holmes telling Dr John Watson in ‘The “Gloria Scott”’: ‘Trevor was the only man I knew, and that only through the accident of his bull terrier freezing onto my ankle one morning as I went down to chapel.’[10]

(Sidney Paget, Strand magazine illustration to ‘The “Gloria Scott”‘)

Do I find this stuff diverting? Why yes, in between those other matters of life and love and death and war. Some varied reading and even some varied writing, on the better days. But there are also visits to the vet with Harry the cat, the usual budget of human aches and pains, as well as that constant screaming of the world outside these walls. Winter, no doubt, is coming. Yet there are still pockets of sense and sanity to be found. One of my latest is the excellent Melissa Harrison’s new Witness Marks (‘A monthly miscellany from a little Suffolk cottage: nature and the seasons, poetry, books and writing, thoughts on creativity, news and Qs’).

https://mzharrison.substack.com/

I read, listen, enjoy and – yes – learn a few things.

Notes

[1] James Boswell, Life of Johnson, edited by R. W. Chapman, revised by J. D. Fleeman, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), 1338.

[2] The Cantos of Ezra Pound, fourth collected edition (London: Faber and Faber, 1987), 76/460.

[3] Questioning Minds: The Letters of Guy Davenport and Hugh Kenner, edited by Edward M. Burns, two volumes (Berkeley: Counterpoint Press, 2018), II, 904. Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language was published in 1755.

[4] Clare Leighton, Four Hedges: A Gardener’s Chronicle (1935; Toller Fratrum: Little Toller Books, 2010), 40; Letters of D. H. Lawrence III, October 1916–June 1921, edited by James T. Boulton and Andrew Robertson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 21.

[5] Mick Herron, Bad Actors (London: John Murray, 2022), 339-340.

[6] Mick Herron, Why We Die (London: John Murray, 2020), 122.

[7] William Carlos Williams, Kora in Hell (1920), in Imaginations (London: MacGibbon and Kee, 1970), 32.

[8] Margery Allingham, Sweet Danger (1933; Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1950), 44.

[9] In Daniel Karlin, editor, The Penguin Book of Victorian Verse (London: Penguin Books, 1997), 125.

[10] Arthur Conan Doyle, The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, 2 volumes, edited with notes by Leslie S. Klinger (New York and London: W.W. Norton and Company 2005), I, 502. Klinger quotes Nicholas Utechin’s Sherlock Holmes at Oxford to the effect that Trevor’s bull terrier ‘has been a subject more disputed by scholars in the Sherlockian world than any other—animal, vegetable, or mineral’, the issue of which university Holmes attended being a highly contentious one and the dog a crucial clue.