St Thomas grey, St Thomas grey,

The longest night and the shortest day.[1]

‘I might be lost’, Adolfo Barberá said to Iain Sinclair, ‘but I know where I am.’[2] Many of us can say, with confidence, that we’re lost. Do we know where we are? We now appear to be quarantined on an island off the coast of Europe. There are features discernible in this winter solstice landscape and the main one is probably recurrence, repetition, things going round again. I find the same quotations running through my head, for sure, such as Guy Davenport’s, ‘In our time we long not for a lost past but for a lost future’, or this from Charles Olson:

What has he to say?

In hell it is not easy

to know the traceries, the markings[3]

In England, the pattern is established, if not one to emulate. Receive the advice, ignore it, then eventually act on it—too late—and retreat from it too soon. Repeat. Even the—what is the latest euphemism, ‘low information voters’?—yes, it must surely be dawning on even those co-operative souls that the Leave UK gang hasn’t handled matters quite as well as they might have done. The news from Kent, on the other hand, must be hugely reassuring to those who voted for that Brexit thing.

(Via BBC)

Has this country ever been governed so badly? As we edge, run or career towards the end of 2020, it occurs to me that I’ve been reading for dear life these last months, as if the relentless turning of pages could offset to some degree the idiocy and dishonesty of this government and, frankly, the sheer insanity of the United States administration and many of its supporters.

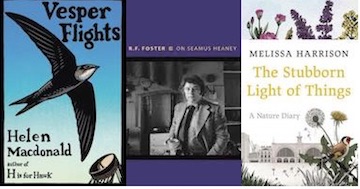

‘Prose is the devil’, Ezra Pound once remarked in a letter to Alice Corbin Henderson, poet and assistant editor to Harriet Monroe at Poetry magazine. ‘ALL prose is the devil, except perhaps a little of Flaubert and De Maupassant.’[4] Nevertheless, pace Ezra—who was, I note in passing, a clue in yesterday’s speedy crossword, ‘troubled US poet’, though why he should be described as ‘troubled’, more so than Robert Lowell or Anne Sexton or John Berryman or Sylvia Plath or a hundred others, who can say?—it’s been mainly prose that I’ve been reading, although, in conjunction with Roy Foster’s incisive book on Seamus Heaney, I found myself reading (or sometimes rereading) the first six books of Heaney’s poetry.[5]

Some tremendous books have passed before my eyes this year, though it still feels hugely pleasing to be back with Maigret—in Antibes at the moment. There have been jaunts avec M. Simenon in previous months, and a few Golden Age authors such as Margery Allingham but, beyond those, I took in several of the year’s high profile titles. Still, not for the first time, some of the best things were older – but, in either case, most seemed to be by women this time around.

Some of them cropped up on several Books of the Year lists: Maggie O’Farrell’s impressive Hamnet and Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light (I added her collection of pieces from The London Review of Books, Mantel Pieces, and—one I’d missed—her fine memoir, Giving Up the Ghost). Francesca Wade’s Square Haunting was a blast and Helen Macdonald’s collection of essays, Vesper Flights, was marvellous, one of my books of the year for sure. After Elena Ferrante’s The Lying Life of Adults, I read her earlier, very unsettling The Lost Daughter.

Not quite so new but add Annie Ernaux and Mary Gaitskill, just about anything by either of them: Ernaux seems to have reinvented or recast the genre of autobiography (Fitzcarraldo Editions have done five of hers in translation now); while Gaitskill seems to possess something like perfect pitch.

Maybe the most fun was either Craig Brown’s One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time, six hundred plus pages which I ripped through in a couple of days; Ysenda M. Graham’s British Summer Time Begins; or Paraic O’Donnell’s two novels, The Maker of Swans and The House on Vesper Sands, which came recommended on Melissa Harrison’s podcast, ‘The Stubborn Light of Things’, also the title of the collection of her monthly nature diary columns in The Times, certainly another of my books of the year.

‘The year’, ‘the year’ – an endlessly recurring phrase, often in conjunction with such optimistic sentiments as ‘the next one can’t be worse’ and ‘soon be over’.

Ah, well.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Bonnie Blackburn and Leofranc Holford-Strevens, The Oxford Companion to the Year (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 505.

[2] Iain Sinclair, ‘Diary’, London Review of Books, 21 May 2020), 40.

[3] Guy Davenport, Apples and Pears (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1984), 63; Charles Olson, ‘In Cold Hell, in Thicket’, in The Collected Poems of Charles Olson, edited by George F. Butterick (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 155.

[4] The Letters of Ezra Pound to Alice Corbin Henderson, edited by Ira B. Nadel (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993), 43.

[5] R. F. Foster, On Seamus Heaney (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020).