(‘The Ash Yggdrasil’ from Aasgard and the Gods, by Wilhelm Wägner)

‘I remember going on to think that Ragnarök seemed “truer” than the Resurrection’, the narrator of A. S. Byatt’s story, ‘Sugar’, writes, having known, as a child, the 1880 book Asgard and the Gods.[1]

There’s a peculiar fascination about those moments in a work of art when other practitioners are evoked, quoted or alluded to, especially when the source is altered. Often enough, this is because the writer is quoting from memory: while George Orwell usually announces that he’s about to do so, others engage in the same practice without any such explicit statement, not infrequently getting things almost—but not quite—right. In a letter to G. K. Chesterton (6 July 1928), T. S. Eliot wrote: ‘The last time that I ventured to quote from memory in print, a correspondent [ . . . ] pointed out that I had made twelve distinct mistakes in well-known passages of Shakespeare.’[2] Joseph Conrad used lines from Spenser’s Faerie Queene (I, ix, 359-360) as the epigraph to his novel The Rover (1923), and the same lines were later incised on his gravestone at Canterbury: ‘Sleep after toyle, port after stormie seas,/ Ease after warre, death after life does greatly please’. When they reappeared at the close of the ‘English’ text of Ford Madox Ford’s No Enemy (there is an appendix with the original French version of an earlier chapter in English), there were a few differences. ‘Sleep’ becomes ‘rest’ (a resonant word in Ford’s writings), ‘ease after warre’ is excluded, even though Ford wrote much of the book in 1919, having just been gazetted out of the British army after serving both at home and in France and Flanders, ‘death after life’ goes too, since he is celebrating survival, if among a number of ghosts. This is far from simple ‘misquoting’ or ‘misremembering’.[3]

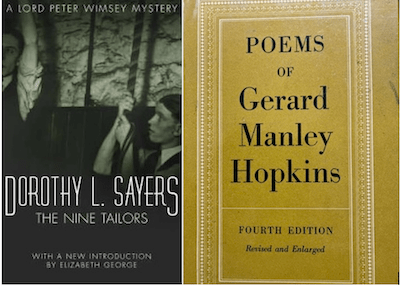

There’s a moment in Dorothy Sayers’ 1934 novel, The Nine Tailors—‘O my, what a lovely piece of work’, Guy Davenport commented, having just read Sayers’ book—when Lord Peter Wimsey, watching a coffin go off up the road, slips into reverie, or stream of consciousness, and suddenly comes up with a chunk of what was immediately familiar to me, though it took a minute or two to identify it as a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins called ‘That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire’:

‘In a flash, at a trumpet crash,

I am all at once what Christ is, | since he was what I am, and

This Jack, joke, poor potsherd, | patch, matchwood, immortal diamond,

Is immortal diamond.’[4]

These are characteristically arresting lines, but the poem’s full title is ‘That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the Comfort of the Resurrection’, and there is a striking gap, an elision, in the passage that occurs in Wimsey’s thoughts: the line, ‘I am all at once what Christ is, | since he was what I am, and’, is missing.[5]

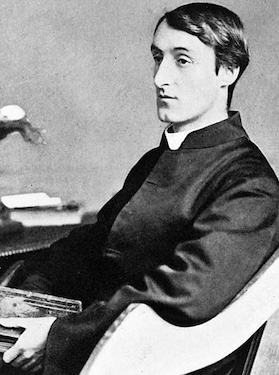

Hopkins wrote to his friend, the poet Robert Bridges, on 25 September 1888, that, while the sonnet he’d recently sent Bridges on the Heraclitean fire had distilled a lot of early Greek philosophical thought, perhaps ‘the liquor of the distillation did not taste very Greek’. He added: ‘The effect of studying masterpieces is to make me admire and do otherwise’—which seems eminently reasonable.[6]

(Gerard Manley Hopkins)

Hopkins—Jesuit priest, classics professor—is, as W. H. Gardner wrote, ‘a religious, not merely a devotional, poet. Religion, for him, was the total reaction of the whole man to the whole of life’ (‘Introduction’ to Poems, xxxv). A good many of his poems are addressed directly and vividly to God, as in the first stanza of the first major poem, ‘The Wreck of the Deutschland’:

Thou mastering me

God! giver of breath and bread

World’s strand, sway of the sea;

Lord of living and dead

Thou has bound bones and veins in me, fastened me flesh,

And after it almost unmade, what with dread,

Thy doing: and dost thou touch me afresh?

Over again I feel thy finger and find thee.

‘The Windhover’ is dedicated ‘To Christ our Lord’, ‘Pied Beauty’ begins: ‘Glory be to God for dappled things’, ‘The Loss of the Eurydice’ is addressed ‘O Lord’ and a late sonnet begins: ‘Thou art indeed just, Lord, if I contend/ With thee’. The ‘terrible sonnets’, evidence of great stress, even ‘desolation’, also centrally concern his relationship with God:

I am gall, I am heartburn. God’s most deep decree

Bitter would have me taste: my taste was me;

Bones built in me, flesh filled, blood brimmed the curse.[7]

Religious themes featured early in Sayers’ writing life and became more central later, in her many plays and her translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy. This rector’s daughter may have had both father and rectory in mind when she wrote The Nine Tailors. Mr Venables is scholarly, very amiable and extremely absent-minded, and Lord Peter Wimsey comes to regard him with affection and respect. Could Sayers have felt that the line she omitted from Hopkins’ poem might have seemed blasphemous to some readers, an issue further complicated by its occurring in her hero’s thoughts? At one point, Wimsey is confronted by a visiting card on a wreath, purporting to be from him but actually supplied by his manservant Bunter (who had been Sergeant to Major Wimsey in the First World War). The card includes a biblical reference, Luke xii, 6. ‘“Very appropriate,” said his lordship, identifying the text after a little thought (for he had been carefully brought up)’ (The Nine Tailors, 133). It’s probably safe to assume that Sayers too had been ‘carefully brought up’ in that respect.

Notes

[1] A. S. Byatt, Medusa’s Ankles: Selected Stories (London: Vintage, 2023), 37. Her Ragnarok: The End of the Gods was published in 2011.

[2] Quoted in a note to the epigraph of ‘Gerontion’, in The Poems of T. S. Eliot. Volume I: Collected and Uncollected Poems, edited by Christopher Ricks and Jim McCue (London: Faber & Faber, 2015), 469.

[3] Paul Skinner, ‘Just Ford – an Appreciation of No Enemy: A Tale of Reconstruction’, Agenda, edited by Max Saunders, 27, 4/ 28, 1 (Winter 1989/ Spring 1990), 103-109 (105).

[4] Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Fourth edition, revised and enlarged, edited by W. H. Gardner and N. H. Mackenzie (London: Oxford University Press, 1967), 105-106. These are the last lines of the poem.

[5] The Nine Tailors (1934; with an introduction by Elizabeth George, London: New English Library, 2003), 122. Davenport’s enthusiasm (he writes the title as The Nine Taylors) is expressed in a letter to Hugh Kenner, 10 April 1967: Questioning Minds: The Letters of Guy Davenport and Hugh Kenner, edited by Edward M. Burns, two volumes (Berkeley: Counterpoint Press, 2018), II, 888.

[6] The Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins to Robert Bridges, edited by Claude Colleer Abbott (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1955), 291.

[7] ‘I wake and feel the fell of dark’, Poems, 101.