(John Frederick Herring II, ‘Farmyard with Saddlebacks’: Haworth Art Gallery)

The year has turned but, unfortunately, the direction of human travel has not, bringing to mind the old ballad:

It was mirk, mirk night, there was nae starlight,

They waded thro’ red blude to the knee;

For a’ the blude that’s shed on the earth

Rins through the springs of that countrie.[1]

We have long passed ‘that blessed season’, which Saki so liked, ‘between the harshness of winter and the insincerities of summer’.[2] I read hungrily, if not always strictly relevantly to the projects currently in train.

‘Every time I consider autobiography’, Guy Davenport wrote to the author and publisher W. C. Bamberger in June 2000, ‘my mind instantly runs to senseless (but satisfying) recrimination.’ He went on to detail the losses – due to carelessness or dishonesty – of valued letters, priceless association copies of books, drawings made to accompany essays or stories, which were jettisoned by editor or publisher once the material had been printed. ‘One of them was a Greek mask I’d worked on for a week, pen and ink, perhaps the finest drawing I’ve ever done.’ He added: ‘And there’s the art book with color plates that a fellow grad student at Harvard borrowed and kept his place with a slice of bacon,’ before concluding: ‘L’enfer, c’est les autres.’[3]

(Portrait of Lady Charlotte Harley as Ianthe: drawn by Richard Westall, engraved by W. Finden)

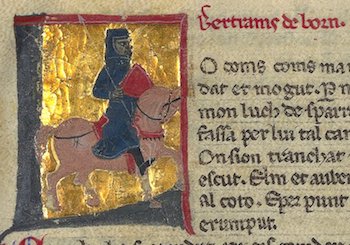

Bacon, you say. . . . Francis and Roger and Francis, and how many more? There was Lady Charlotte, wife of Colonel Anthony Bacon of the Lancers and daughter of the Earl of Oxford. Bacon was involved in the War of the Brothers, 1832-1834 (Pedro and Miguel) in Portugal, in the cause of Dom Pedro. Charlotte was the ‘Ianthe’ to whom, at the age of ten, Byron wrote his introductory stanzas at the beginning of Childe Harold.[4]

Such is thy name with this my verse entwined;

And long as kinder eyes a look shall cast

On Harold’s page, Ianthe’s here enshrined

Shall thus be first beheld, forgotten last[5]

There was Sir Nicholas Bacon, Keeper of the Great Seal to Queen Elizabeth I, who built a fine house mentioned by Ronald Blythe in his discussion of Stiffkey, a Norfolk village more famous since for the rector, Harold Davidson, who was defrocked after being charged with immorality – and died as a result of being mauled by a lion.[6] Francis – not the painter – supplies two epigraphs to Dorothy Sayers in her 1935 novel, Gaudy Night.[7] More entertainingly on the bacon front, Peter Vansittart writes that, until the Hundred Years’ War, the patron saint of England was Edward the Confessor. ‘Then Edward III, in debt to Genoese bankers, replaced him with their patron, the more aggressive St George, who was not to escape the attention of the supreme English ironist, Gibbon: he dismissed George as a dishonest bacon contractor, loathed by Christian and pagan alike.’[8]

Anyone fretfully wondering how long it will take Ford Madox Ford to rock up can now put their mind at rest. In Ancient Lights, Ford segued from a memory of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s limericks to an anecdote about ‘another poet, a descendant of many Pre-Raphaelites, of whom it was related that whilst reading his friend’s valuable books at that friend’s breakfast table he was in the habit of marking his place with a slice of bacon.’ He added that he knew this anecdote to be untrue.[9] How might he be so sure? Slip forward twenty years and Ford is remembering his doctor, Tebb, with whom Ford stayed for a while when the good doctor was treating him in the late stages of a breakdown. He writes of Tebb inventing ‘one of the most ingenious lies’ about his guest: that Ford marked his place in Tebb’s ‘priceless first editions and incredibly sumptuous large paper copies with a slice of bacon.’[10]

Reading the recently published collection of shorter pieces by Hilary Mantel—and reminding myself of just how funny she can be—I come across an article, written for Vogue, on perfumes. Mantel remarks: ‘What women have always wanted to know is what scent drives men wild; researchers have the answer, say Turin and Sanchez [co-authors of the book Perfumes: The Guide], and it’s bacon.’[11] It’s just possible that this news may not have brought unalloyed delight to those inquiring women.

Bacon features largely in Ford’s letters around the end of the First World War, given the twin factors of meat rationing (introduced in 1918) and Ford’s own pig-breeding ambitions. ‘I got as far as the above’, he wrote to Stella Bowen in a letter that stretched over two days (28-29 April 1919), ‘when sleep overtook me—or rather sleepiness, for, when I went to bed I cd not get to sleep. I fancy an unmixed diet of bacon is telling on my liver.’[12]

William Cobbett – farmer, MP, soldier, traveller, radical journalist, printer, avid dispenser of practical advice to the common people (‘The Poor Man’s Friend’) – who took a positive view of pigs, wrote in his Cottage Economy:

A couple of flitches of bacon are worth fifty thousand Methodist sermons and religious tracts. The sight of them upon the rack tends more to keep a man from poaching and stealing than whole volumes of penal statutes, though assisted by the terrors of the hulks and the gibbet.[13]

It was also a matter of personal preference. On one of his famous rural rides, he arrived at Ashurst ‘(which is the first parish in Kent on quitting Sussex)’, where, ‘for want of bacon’, he was ‘compelled to put up with bread and cheese for myself. I waited in vain for the rain to cease or to slacken, and the want of bacon made me fear as to a bed.’[14] So he rode on through the night and the driving rain. Better drenched than baconless.

No mention of pork or bacon, unsurprisingly, in our Syrian and Palestinian cookbooks, nor, surely, in Claudia Roden’s The Book of Jewish Food? But yes, there is an entry in her index, which turns out to be connected with her visit to El Molino in Granada, a centre for research into the history of Spanish food. She was told that some Marranos, forced by the Inquisition to convert to Christianity, ‘made a point of cooking pork to protect themselves from charges by the Inquisition of continuing to practise their old religion.’[15]

The Librarian and I were recently comparing our inability to remember jokes. Some people have a repertoire of hundreds, others recall not a single one. The Librarian offers only one: it concerns the Pink Panther and she first heard it decades ago. I cudgel my brains and offer a knock knock joke dredged from some long unvisited cerebral recess:

Knock knock! (Who’s there?) Egbert! (Egbert who?) Egbert not bacon!

A brief, pitying smile. She murmurs, with visible effort, ‘That’s quite funny.’

It’s the way I tell them.

Notes

[1] ‘Thomas the Rhymer’, in The Oxford Book of Ballads, edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1910, reprinted 1932), 3.

[2] ‘The Romancers’, The Short Stories of Saki (London: The Bodley Head, 1930), 311.

[3] Guy Davenport, I Remember This Detail: 40 Letters to Bamberger Books, edited by W. C. Bamberger (Whitmore Lake, Michigan: Bamberger Books, 2022), 79-80. The French sentence is Jean Paul Sartre’s famous line from his play Huis Clos (No Exit).

[4] Rose Macaulay, They Went to Portugal (1946; London, Penguin Books, 1985), 307.

[5] Lord Byron, Selected Poems, edited by Susan J. Wolfson and Peter J. Manning (London: Penguin Books, 1996), 60.

[6] Ronald Blythe, The Age of Illusion: England in the Twenties and Thirties 1919-40 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1964), 156.

[7] Dorothy Sayers, Gaudy Night (1935; London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2016), Chapters 3 and 17.

[8] Peter Vansittart, In Memory of England: A Novelist’s View of History (London: John Murray, 1998), 42.

[9] Ford Madox Ford, Ancient Lights and Certain New Reflections (London: Chapman and Hall, 1911), 44, 45.

[10] Ford Madox Ford, Return to Yesterday: Reminiscences 1894-1914 (London: Victor Gollancz, 1931), 305.

[11] Hilary Mantel, ‘At First Sniff’ (2009), in A Memoir of My Former Self: A Life in Writing, edited by Nicholas Pearson (London: John Murray 2023), 332. I also learn from this that Burger King, yes, released a meat-infused scent called ‘Flame Grilled’.

[12] Correspondence of Ford Madox Ford and Stella Bowen, edited by Sondra J. Stang and Karen Cochran (Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994), 109-110.

[13] William Cobbett, Cottage Economy (1823; Oxford University Press, 1979), 103. In past centuries, pigs ‘were kept by everyone, fed economically on scraps, waste, and wild food’: Alan Davidson, The Oxford Companion to Food, Second Edition by Tom Jaine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 49.

[14] William Cobbett, Rural Rides, edited by George Woodcock (1830 edition; Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1983), 171-172.

[15] Claudia Roden, The Book of Jewish Food (London: Viking, 1997), 332.