(Horatio McCulloch, Loch Katrine: Perth Art Gallery; managed by Culture Perth and Kinross)

(‘Bussoftlhee, mememormee!’ James Joyce, Finnegans Wake)

I was reading Rosemary Hill’s review of a recent book by Steven Brindle, Architecture in Britain and Ireland: 1530-1830, and the extent to which Henry VIII’s break with Rome was an ‘unmitigated disaster’ for architecture. ‘“The dissolution of the religious houses”, Steven Brindle writes, “tore the heart out of the patronage of … the arts” as it had existed for nine centuries and brought about “the largest redistribution of land since the Norman Conquest”. It would take three generations to begin to recover from this “colossal self-inflicted cultural catastrophe”’.[1]

In the current painful condition of the United Kingdom, the notion of colossal self-inflicted catastrophes brings to mind most readily the ill-conceived and dishonestly presented referendum of 2016, although, with the example in mind of Kipling’s phrase in ‘With the Night Mail’, ‘the traffic and all it implies’,[2] we tend to reflect on Brexit and all it implies. The implications are not pretty. A part-time television critic of my acquaintance, who’d watched a series called ‘The Rise and Fall of Boris Johnson’, observes that it’s very easy to forget how simply and thoroughly ‘a small group of men fucked this country over’. Indeed it is.

Memory is fickle, quite easily manipulated (as is blindingly obvious in our time) but, in any case, a fiction writer of great, if sometimes wayward, abilities. It can also perform extraordinary feats. Katherine Rundell, writing of John Donne’s age, describes how‘ [a] school system which hinged on colossal amounts of memorisation had built a population with the kind of mammoth recall which is, in retrospect, breathtaking’ – listeners returning home to argue over sermons, plagiarise them, make them ‘part of the fabric of their days.’[3] Sylvia Beach recalled reading a line at random from “The Lady of the Lake” – and James Joyce then reciting the whole page and the next ‘without a single mistake’.[4] Scott’s poem is in six cantos, the first of which has 35 stanzas, the second 37 – and the stanzas are not short ones. As for its author’s own powers of recall, James Hogg, in his Domestic Manners and Private Life of Sir Walter Scott, ‘tells of how he once went fishing with Scott and Skene [James Skene of Rubislaw]. He was asked to sing the ballad of “Gilmanscleuch” which he had once sung to Scott, but stuck at the ninth verse, whereupon Scott repeated the whole eighty-eight stanzas without a mistake.’[5]

Jenny Diski wrote that ‘there is nothing so unreliable or delicious as one’s rackety memories of oneself.’[6] And we certainly hear and read a lot about ‘unreliable narrators’. Memory is, of course, both narrator and reliably unreliable. This applies both to ourselves and the wider world (perceived and processed by those same selves). In the ‘Foreword’ to Joan Didion’s South and West: From a Notebook, centred on her trip through the deep South in 1970, Nathaniel Rich discussed how a view of ‘the past’ had been relegated to the aesthetic realm and Didion herself remarked on ‘[t]he time warp: the Civil War was yesterday, but 1960 is spoken of as if it were about three hundred years ago.’[7]

Oddly (though probably not), memory delayed a little in reminding me that my remark about unreliable narrators may be more or less purloined from an essay by Frank Kermode, revisited when I went back to a Conrad novel last year. Nearly one-third of the books I read in 2023 I’d read before, largely due to working on Ford Madox Ford, of course; they were either his own books or Ford-related, directly or tangentially.

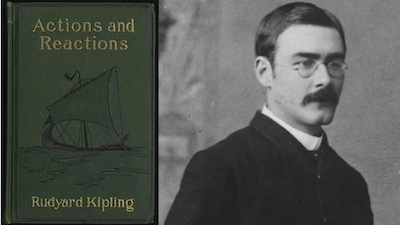

Unsurprisingly, they included ‘that finest novel in the English language’, as Ford once described it. And again: ‘[F]or me, Under Western Eyes is a long way the greatest—as it is the latest—of all Conrad’s great novels.’[8] Once more: ‘That is to say, in common with myself, he regarded the writing of novels as the only occupation for a proper man and he thought that those novels should usually concern themselves with the life of great cities.’ There were two such novels. ‘But although The Secret Agent was relatively a failure, Under Western Eyes with its record of political intrigue and really aching passion has always seemed to me by a long way Conrad’s finest achievement.’[9]

I had read Conrad’s novel of pre-revolutionary politics, betrayal and assassination so long ago that it might almost have been for the first time – almost. It is, no doubt, a tribute to the writing that I found myself consciously offering advice to the student Razumov during his interview with Councillor Mikulin: Shut up! Don’t say another word! Hold your tongue! He can’t, of course. And Ford saw the driving force of much of the book to be personal honour. Of Razumov’s ploy to ‘add a touch of verisimilitude’, having a foolish boy rob his own rich father but then tossing the money from a train window, Ford comments: ‘And the same unimaginative cruelty of a man blindly pursuing his lost honour dignifies Razumov to the end.’[10]

My surviving sense of the book had included Conrad’s known antipathy to Russia (hardly surprising in a Pole born in the Ukraine, part of the Russian Empire but once part of Poland) and his contempt for revolutionaries, which was evident in The Secret Agent. Under Western Eyes was written between two Russian revolutions, published (1911) exactly midway, in fact. But notions of nationality, allegiance and bafflement also shouted aloud ‘Conrad’! Or, perhaps, ‘Konrad Korzeniowski!’ Much of this was to do with that complex process of holding onto a strong sense of one’s native country and culture, while adopting a second language (retaining fluency in the first) – and then a third, while settling in another country and choosing to write in that third language. None of this was made much easier for Conrad by his being attacked on occasion by Polish compatriots for deserting both language and country. Not that migration is ever only a matter of language. H. G. Wells had a couple of digs at Conrad, not only that he spoke English ‘strangely’ but also that ‘[o]ne could always baffle Conrad by saying “humour.” It was one of our damned English tricks he had never learned to tackle.’[11] Under-westernised?

Kermode’s celebrated essay, ‘Secrets and Narrative Sequence’, I’d also read a long time ago.[12] Briefly, he argues that Conrad’s text shows itself obsessed with certain words and images which wholly evade orthodox, ‘common sense’ readings. More, he suggests that the book’s ‘secrets’ are in fact ‘all but blatantly advertised’ (99) and from which, by a curious process of collusion, ‘we avert our attention’ (95). He is pointing to the novel’s constant references to ghosts or phantoms, souls, eyes and, perhaps above all, to the art of writing, more, the materials of writing: black on white, ink on paper, shadows on snow, notebooks, a journal wrapped in a veil. I went back to the essay after reading the novel. It’s true that I found it difficult to see how critics had not seen and grasped – or sought – the significance of the astonishing frequency of such images. Souls, ghosts and related words occur a hundred times, references to eyes more than sixty times, and so on. This is bound to snag the attention of a reader of Ford’s The Good Soldier, an even shorter novel, I think, in which the verb ‘to know’ in its various forms, occurs not far short of three hundred times. ‘What I ask you to believe’, Kermode writes, ‘is that such oddities are not merely local; they are, perhaps, the very “spirit” of the novel’ (97). Difficult not to notice, I said, but cannot be sure of how much that noticeability is related to residual memories of his essay. With a fistful of exceptions, I’m unacquainted with the secondary literature on Conrad which is, I’ve learned, ‘huge, approximately 800 monographs, biographies, edited collections, volumes of letters and catalogues, without counting the hundreds of peer-reviewed papers in the general and specialist literary journals, the untranslated material and the unpublished doctoral theses.’[13]

Richard Parkes Bonington, La Place du Molard, Geneva (Victoria & Albert Museum)

St Petersburg, Geneva. The book is centrally concerned, of course, with Russia: its psychology, Conrad himself suggested, more than its politics. There is also the essential complicating factor of the narrator—‘all narrators are unreliable, but some are more expressly so than others’, as Kermode remarks (yes, that’s the one).[14] A language teacher, English, in love with Natalia Haldin, sister of the executed assassin Victor Haldin, and friendly with their mother. Speaking sometimes in his own voice (whatever the extent to which it’s borrowed) and sometimes through the medium of Razumov’s journal, he repeatedly asserts an inability to understand the Russian character, the Russian soul. He glances down at the letter Natalia is holding, ‘the flimsy blackened pages whose very handwriting seemed cabalistic, incomprehensible to the experience of Western Europe.’ At one point, ‘I could not forget that, standing by Miss Haldin’s side, I was like a traveller in a strange country.’ Again, ‘The Westerner in me was discomposed’ and: ‘I felt profoundly my European remoteness and said nothing, but I made up my mind to play my part of helpless spectator to the end.’ And: ‘To my Western eyes she seemed to be getting farther and farther from me, quite beyond my reach now, but undiminished in the increasing distance.’ One more: ‘And this story, too, I received without comment in my character of a mute witness of things Russian, unrolling their Eastern logic under my Western eyes.’

Continually asserting his incomprehension, the unfamiliarity of what he is observing, he does, of course recall Ford’s John Dowell, to whom it is all a darkness and who repeatedly asserts: ‘I don’t know’. And yet, and yet. There are many suspicious readings of The Good Soldier, some of which ask if Dowell is as unknowing as he appears to be and also, perhaps, what kind of knowledge he does not possess. It is, unusually for Ford, narrated in the first person. In any case, it is fatally easy, waltzing among thornbushes, to catch one’s sleeve on that knowledge of knowing nothing, to recall the famous moment in Eliot’s The Waste Land—‘I knew nothing,/Looking into the heart of light, the silence’—and, remembering his interest in eastern thought and religion, wonder if that knew should be stressed infinitely more than the nothing.

(J. M. W. Turner, Sunrise with a Boat between Headlands: Tate)

Kermode notes that, when Conrad began the book, he called it Razumov: ‘but when it was done (on the last page of the manuscript, in fact) he changed the title to Under Western Eyes. He had found out what he was doing’ (98). I remember the pleasure with which I came across that last sentence: the recognition of the fact that, so often, we find out not only how to do something but what it is we are actually doing – only by doing it. And this, certainly, not just in art.

The novelist and playwright Enid Bagnold described how: ‘Beauty never hit me until I was nine.’ When she arrived in Jamaica as a child: ‘this was the first page of my life as someone who can “see”. It was like a man idly staring at a field suddenly finding he had Picasso’s eyes. In the most startling way I never felt young again. I remember myself then just as I feel myself now.’ She adds, a little later: ‘And what you remember is richer than the thing itself.’[15]

Well, sometimes.

Notes

[1] Rosemary Hill, ‘Des briques, des briques’, London Review of Books, 46, 6 (21 March 2024), 13.

[2] Rudyard Kipling, Actions and Reactions (New York: Scribner’s 1909), 148.

[3] Katherine Rundell, Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne (London: Faber, 2023), 223.

[4] Sylvia Beach, Shakespeare and Company, new edition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991), 71.

[5] John Buchan, Sir Walter Scott (London: Cassell, 1932), 131. The ballad was included in Hogg’s first book, The Mountain Bard (1807).

[6] Jenny Diski, In Gratitude (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), 187.

[7] Joan Didion, South and West: From a Notebook, foreword by Nathaniel Rich (London: 4th Estate, 2017), xviii, 104.

[8] Ford, Thus to Revisit (London: Chapman & Hall, 1921), 90-91; Return to Yesterday: Reminiscences 1894-1914 (London: Victor Gollancz, 1931), 193.

[9] Ford, ‘Introduction’ to Joseph Conrad, The Sisters, edited by Ugo Mursia (Milan: U. Mursia & Co., 1968), 11-30 (14).

[10] Ford, ‘Joseph Conrad’, English Review, X (December 1911), 68-83 (71).

[11] H. G. Wells, Experiment in Autobiography (1934; London: Faber, 1984), 616, 622.

[12] Frank Kermode, ‘Secrets and Narrative Sequence’, Critical Inquiry, 7, 1 (Autumn 1980), 83-101 (references are to this); reprinted in Essays on Fiction, 1971-1982 (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1983), 133-155.

[13] Helen Chambers, review of Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad (London: Reaktion Books, 2020), Last Post: A Literary Journal from the Ford Madox Ford Society, I, 4 (Autumn 2020), 124.

[14] Kermode, 89-90; and see footnote 7: ‘The trouble is not that there are unreliable narrators but that we have endorsed as reality the fiction of the “reliable” narrator.’

[15] Enid Bagnold, Autobiography (London: Century Publishing, 1985), 14, 100.

.

.