Sitting at the kitchen table, a cat within the circle of my arms, flanked by James Baldwin and Walter de la Mare, I was thinking about crocuses.

The poet Edmund Blunden, then serving in the 11th Royal Sussex, ‘heard an evening robin in a hawthorn, and in trampled gardens among the luggage of war, as Milton calls it, there was the fairy, affectionate immortality of the yellow rose and blue-grey crocus.’[1] And: ‘The garden is gay with crocuses’, Ford Madox Ford wrote to John Rodker in March 1920, ‘or shd it be crocoi?’ De la Mare himself was not wholly adverse to a crocus: ‘the crocus soon/ Will open grey and distracted/ On earth’s austerity’; ‘as near, that is, as any name can be to a thing—viz, crocus, or comfit, or shuttlecock, or mistletoe, or pantry’; ‘Miss Curtis would no more have dreamed of sharing this old ghost with, say, Miss Mavor, than a crocus would dream of blossoming at the foot of the North Pole.’[2]

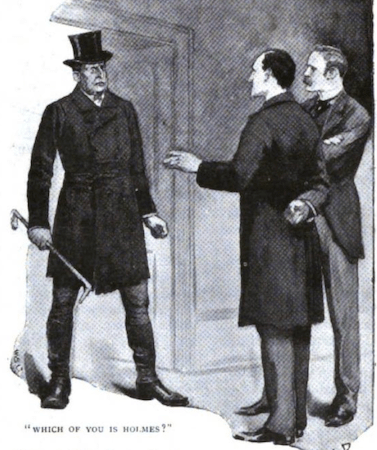

Literary, literary. It was, in fact, while walking in the park, that the Librarian drew my attention to a small group of crocuses, harbingers of spring, a welcome light in the encroaching gloom of the year so far, not least because of seemingly inexhaustible rain. We had rain on twenty-six days out of thirty-one in January. Several places outstripped that, there were floods on the Somerset Levels and elsewhere. But in any case—literary again!—the mention of crocuses always brings to mind Sherlock Holmes, specifically the alarming appearance of the gigantic and ferocious Dr Roylott, who has ‘dashed open’ the door of the sitting-room at 221b Baker Street:

(Illustration by Sidney Paget, Strand Magazine, February 1892)

‘“Which of you is Holmes?” asked this apparition.

“My name, sir; but you have the advantage of me,” said my companion quietly.

“I am Dr. Grimesby Roylott, of Stoke Moran.”

“Indeed, Doctor,” said Holmes blandly. “Pray take a seat.”

“I will do nothing of the kind. My stepdaughter has been here. I have traced her. What has she been saying to you?”

“It is a little cold for the time of the year,” said Holmes.

“What has she been saying to you?” screamed the old man furiously.

“But I have heard that the crocuses promise well,” continued my companion imperturbably.’[3]

The promise of crocuses—or should it be crocoi? Promises, promises. Spring, yes, and all that it connotes. Or, perhaps, all that it used to connote.

‘The past has consequences in the present regardless of whether we know what happened in it; learning the history makes those consequences intelligible.’[4]

The month recently ended will soon be a finite, measurable chunk of that past, a blood smear on some historian’s page. Harold Wilson may or may not have said that a week is a long time in politics; Joseph Chamberlain, some eighty years earlier, is fairly reliably recorded as asserting that there’s no use in looking beyond the next fortnight.

Glancing around at a volatile and feverish world I was about to remark in an email to a friend that—hardly surprisingly—I seemed to be suffering from ‘the English disease’. I meant melancholia but remembered just in time that understanding of the term has varied over time, taking in rickets, a sluggish economy caused by industrial unrest, bronchitis, football hooliganism and more: ‘The English disease, a love of Nature, was inborn in her’, Virginia Woolf wrote of her heroine/ hero Orlando.[5]

(Orlando, Hogarth Press, 1928)

Among the many pleasures of reading published diaries are the references to—or, sometimes, the lack of them, or delayed enlargement on them—what are later viewed as hugely significant events. I was recently reading Helen Garner’s impressive and enjoyable How To End a Story: Collected Diaries, 1978-1998 and seeing ‘The army has entered Tiananmen Square and machine-gunned students’ or ‘People are sitting on top of the Berlin Wall. They’re chipping chunks out of it with chisels, for souvenirs’. I wonder if some of what’s occurring now will be reducible in time to one or three or five lines. In what form will the United States survive? Will liberal or left of centre politicians learn how to do politics in this online, social media age so resistant to accurate information and inconvenient facts? Will Europe get its act—economics, security—together? I note various leaders’ recent responses as they finally accept that the current version of the United States is neither friend nor ally, and recall that appeasement didn’t work too well in the 1930s and is unlikely to do so now.

‘I imagine that one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, that they will be forced to deal with pain’, James Baldwin wrote in ‘Notes of a Native Son’, first published as ‘Me and My House’ in November 1955.[6] Adam Shatz’s recent essay about the current situation in the United States, first delivered as a lecture, begins with Baldwin, who is also referenced in the piece’s title, ‘Another Country’ (Baldwin’s third novel). Shatz remarks that, though both parties have been ‘complicit in the creation of the imperial presidency and a neoliberal economic order’, ‘anyone who cares about the stability of the republic might have reason to regret the disintegration of moderate Republicanism, one of the defining structural features of American political life.’[7] We have suffered a version of that in this country too, with the collapse and near-disappearance of moderate Conservatism, those figures to whom we were totally opposed twenty or more years ago appearing now almost as beacons of light, intelligence and sweet reason, compared to the current crew. If I’d seriously believed then that the political landscape would be what it is, that certain individuals would be regarded as acceptable public servants, even as plausible contenders for government office, I would have sought medical help as a matter of urgency. Mais passons. There is always the rain. . .

‘If there’s much more of this’, I say to the Librarian as we trudge wetly home, ‘we might be living in a J. G. Ballard novel.’ We pass the City Farm, where their prize hens are sheltering, huddled together, beneath their chicken coop. It occurs to me that a number of Ballard novels might qualify though I was referring specifically to The Drowned World, which is, of course, concerned with rather more than water: ‘Sometimes he wondered what zone of transit he himself was entering, sure that his own withdrawal was symptomatic not of a dormant schizophrenia, but of a careful preparation for a radically new environment, with its own internal landscape and logic, where old categories of thought would merely be an encumbrance.’[8]

There has been very little brightness. Too often the sliver of sunlight glimpsed earlier in a day is—fittingly, in the current political climate—neither sincere, truthful, friendly or sustained. I’ve had the odd drenching myself but—full-length waterproof coat! umbrella! Englishman!—with no apparent ill-effects. Others have not always been so lucky. Perhaps ‘the most dramatic incident’ of Lewis Carroll’s life, Penelope Fitzgerald remarked, was the river expedition to Nuneham when the whole party, ‘including his aunt, two of his sisters, and Alice herself, got wet through and had to be taken to a friend’s house to dry off. In 1898, almost as an afterthought, Dodgson died of a cold and cough.’[9]

(Edith, Lorina and Alice Liddell)

Needless to say, awash as the country is, the disastrous privatisation of this vital resource, with its attendant greed and incompetence, has resulted in towns and villages running out of water, waiting days for their supplies to be reconnected or warned that they may have to be abandoned in the fairly near future. There is, apparently, a great deal more trouble to come: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2026/jan/22/what-happens-england-water-run-out-drought-tunbridge-wells

The drought last summer was not as bad as it might have been because preceded by a wet autumn and winter, reservoirs well-filled and groundwater in a healthy state – certainly not as bad as that recalled by the novelist Violet Hunt. ‘We were in for a hot July—it was the year 1911 when heat and drought drove men mad, caused the cattle that supported them to be lean and perish, filled the Courts with murder and rapine, inflamed Strike committees, and incensed three nations to the verge of war for want of a little rain that might have staunched their hissing hatreds.’[10]

‘For want of a little rain.’ Just so.

Notes

[1] Edmund Blunden, Undertones of War (1928; revised edition, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1982), 117.

[2] Respectively, ‘The Children of Stare’, Collected Poems (London: Faber and Faber, 1979), 21; ‘Pigtails Ltd’, Walter de la Mare, Collected Stories for Children, edited by Giles de la Mare (London: Giles de la Mare Publishers Limited, 2006), 7; ‘The Picnic’, Short Stories, 1927-1956, edited by Giles de la Mare (London: Giles de la Mare Publishers Limited, 2001), 180.

[3] Arthur Conan Doyle, ‘The Adventure of the Speckled Band’, in The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, 2 volumes, edited with notes by Leslie S. Klinger (New York and London: W.W. Norton and Company 2005), I, 241-242..

[4] Sarah Churchwell, The Wrath to Come: Gone With the Wind and the Lies America Tells (London: Head of Zeus, 2022), 11.

[5] Virginia Woolf, Orlando (1928; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 137.

[6] James Baldwin, ‘Notes of a Native Son’, in Collected Essays, edited by Toni Morrison (New York: Library of America, 1998), 7.

[7] Adam Shatz, ‘Another Country’, London Review of Books 48, 2 (5 February 2026), 3-10.

[8] J. G. Ballard, The Drowned World (London: Fourth Estate, 2012), 14.

[9] Penelope Fitzgerald, ‘In the Golden Afternoon’: A House of Air: Selected Writings, edited by Terence Dooley with Mandy Kirkby and Chris Carduff (London: Harper Perennial, 2005), 81.

[10] Violet Hunt, The Flurried Years (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1926), 177-178.