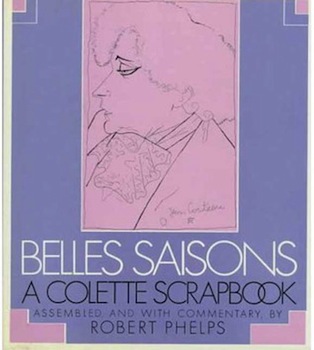

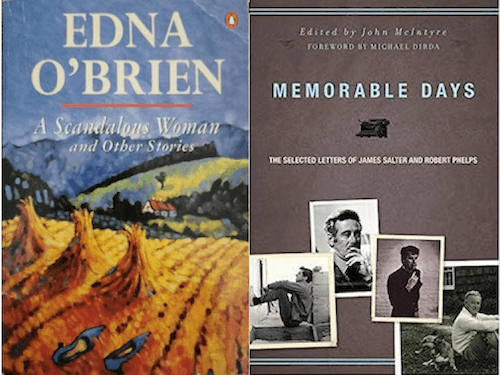

In the past couple of weeks, I’ve read a lot of tributes to, and memories of, Edna O’Brien, who died on 27 July. I know some of her books but clearly not enough of them. My favourite story about her is probably that in one of James Salter’s letters to Robert Phelps (a wonderful volume), dated 2 November 1972. Salter mentions at the top of the letter that Ezra Pound has died (it had happened the previous day) and reports on ‘Dinner last night with Edna O’Brien and her son.’ She was nervous about the play opening that night, A Pagan Place, from her novel of the same title. ‘She ate everything with her fingers’, Salter wrote, ‘lamb, clumps of spinach, they didn’t even have to wash her fork.’ O’Brien told him about a long story, ‘Over’, which the New Yorker was publishing. ‘She was marvelous, she could recite great passages, long pieces of her story, there was one sentence saying something like: I liked your voice and the way you poured things and your fingering.’ Her editor, ‘in the vastly inquisitorial galleys, wrote: “Mr Shawn [editor of the magazine, 1952-87] thinks this is a little too strong for us.” So Edna changed it to “and your fucking.”’[1]

Alas, ‘fingering’ seem to have made a comeback, certainly when the story was collected in A Scandalous Woman and other stories (1974): ‘Do you still use the same words exactly, and exactly the same caresses, the same touch, the same hesitation, the same fingering? Are you as shy with her as with me? If only you had had courage and a braver heart.’[2]

As for the change, was it made around that time, by reluctant but common consent, or later – perhaps at the proof stage? Proofs!

Looking for the umpteenth time at the draft of a Ford Madox Ford letter (its notes, rather), I wondered about an ‘enormous slap of cake’ and was dispirited by my glimpse of a poet named ‘William Worsworth’. In the first instance, I looked back to the original article and found—almost regretfully because I was warming to a ‘slap of cake’—that it was indeed ‘slab’. I didn’t need to check on the poet but simply inserted the missing letter. Any offended descendants of the poet Worsworth should write in.

Reporting on his struggle with the page proofs of The Pound Era (probably—but only probably—a longer book than this volume of letters will turn out to be), Hugh Kenner wrote to Guy Davenport: ‘It is demoralizing to find “viligance” for “vigilance” in a line one has already read 4 times.’[3] And any writer, editor or proofreader will be familiar with that feeling.

(Hugh Kenner via The National Post; photo by the scholar Walter Baumann)

Of an earlier book (on Samuel Beckett), Kenner had confided: ‘In accordance with my normal policy of imitating the specimen’s style, I rigorously trained myself to write dead-pan declarative sentences page after page, with here and there flickers of irony gleaming through the performance. I hope you like the effect.’ And proofs were not always an ordeal: fun was there for the taking, as he added to Davenport a week later: ‘I forget whether I told you that I have spliced bits of Happy Days into my Beckett proofs, so adroitly (I think) that no one will be able to tell they were not there all along.’[4]

In turn, Davenport mentioned, in his ‘Pergolesi’s Dog’—‘We are never so certain of our knowledge as when we’re dead wrong’—that ‘The New York Review of Books once referred to The Petrarch Papers of Dickens and a nodding proofreader for the TLS once let Margery Allingham create a detective named Albert Camus.’[5]

Sylvia Beach recalled the printer of Ulysses, Monsieur Dalantière, supplying as many sets of proofs as James Joyce wanted—‘he was insatiable’—and they were all ‘adorned with the Joycean rockets and myriads of stars guiding the printers to words and phrases all around the margins. Joyce told me that he had written a third of Ulysses on the proofs.’ Right up to the last minute, ‘the long-suffering printers in Dijon were getting back these proofs, with new things to be inserted somehow, whole paragraphs, even, dislocating pages.’[6] My Viking Press edition of Finnegans Wake (New York: 4th printing, 1945) contains a list of corrections of misprints, made by Joyce: fifteen closely printed pages of double columns, in which such phrases as ‘insert comma’ and ‘delete stop’ abound.[7] The book was published in 1939, less than two years before Joyce’s death, after decades of eye trouble, cataracts, glaucoma and much else.

(Thomas Hardy, early 1920s via The Guardian)

For the professional writer, of course, proofs are a constant, whether burden or blessing. . ‘I am bringing out a stodgy novel this autumn’, E. M. Forster wrote to his friend Malcolm Darling (22 August 1910) ‘but I think I told you this. It’s called Howards End, and dealeth dully with many interesting matters. I am correcting proofs now.’[8] Sylvia Townsend Warner reported in her diary: ‘Proofs and ten thousand letters.’ She added the more specific news that: ‘Thomas Hardy has died. Dorset will mourn – a more rare and antique state of things than England mourning.’[9]

As yet, a very long way from reaching the proof stage, I am still inching through Word documents. As for the errors that other people have missed in the proofs of their texts, errors I come across almost daily in my reading, that would be altogether too long a tale to tell. . .

Notes

[1] Memorable Days: The Selected Letters of James Salter and Robert Phelps, edited by John McIntyre, foreword by Michael Dirda (Berkeley, California: Counterpoint, 2010), 95-96. Phelps, in his letter of 10 November, commented: ‘I’ll never forget Miss O’Brien’s way with spinach’ (97). ‘Over’ appeared in The New Yorker (24 November 1972).

[2] Penguin Books edition (Harmondsworth, 1976), 56.

[3] Letter of 21 June 1971: Questioning Minds: The Letters of Guy Davenport and Hugh Kenner, edited by Edward M. Burns, two volumes (Berkeley: Counterpoint Press, 2018), II, 1357.

[4] Letters of 27 September 1961 and 6 October 1961: Questioning Minds, I, 37, 39.

[5] Guy Davenport, Every Force Evolves a Form (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1987), 145. Allingham’s Albert Campion would probably have been amused.

[6] Sylvia Beach, Shakespeare and Company, new edition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991), 58.

[7] See, on Joyce ‘adding commas’, Richard Ellmann, James Joyce (new edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), 731, 734.

[8] Selected Letters of E. M. Forster, Volume One: 1879-1920, edited by Mary Lago and P. N. Furbank (London: Collins, 1983), 114.

[9] The Diaries of Sylvia Townsend Warner, edited by Claire Harman (London: Virago Press, 1995), 11: entry for 12 January 1928. Hardy had died in Dorchester the previous day, at the age of 87.