(Philip Wilson Steer, Dover Coast: York Art Gallery)

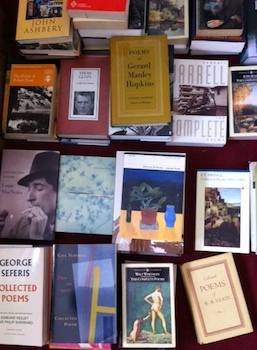

Another last warm and sunny afternoon of autumn. How many more can there be? With the Librarian in the office for a pretty full day, so not available for the lunchtime stroll, I walk alone in the park and succumb to the temptation to recall (and recite) the handful of poems that, at one time or another, I’ve committed to memory. Committed they may have been but seem, for the most part, to have escaped or at least to be out on parole.

Matthew Arnold’s ‘Dover Beach’ is worse than shaky and, in its current state, Marvell’s ‘To His Coy Mistress’ would probably not detain her for a moment. A bit of Pound, a bit of Yeats and a fragment of Elizabeth Bishop all hold steady, while a couple of others improve with work, which necessitates keeping a wary eye open – and an ear, given the increasing tendency of people to rush up behind you on bicycles or accursed electric scooters. Robert Lowell’s ‘Skunk Hour’ (dedicated to Bishop) yields a little to pressure:

Nautilus Island’s hermit heiress still

something something

her sheep still graze above the sea

Two men, walking briskly but not quite briskly enough, so staying almost exactly the same distance behind me, fairly close and, worse, very gradually nearing. . .

Her farmer

Is first selectman in our village;

she’s in her dotage.

We’re sailing now. Ah:

Thirsting for the hierarchic privacy

of Queen Victoria’s century,

she buys up all

the eyesores facing her shore,

and lets them fall.

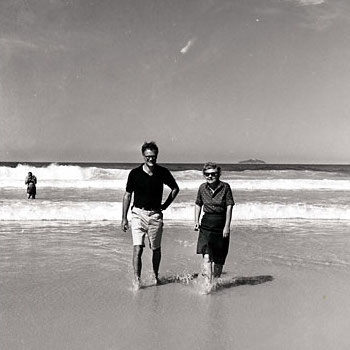

(Lowell and Bishop in Brazil, 1962. Photo: Vassar College Library via the New Criterion)

But then there’s some confusion in the order of half-remembered stanzas, though I have most of the mother skunk’s activities in the final one. Move on to surer ground, anyway, the much-learned, almost-all recollected ‘Bagpipe Music’.

Though here a slight pause for the woman standing with her dog at the top of a slope below the play area. Is it a Pointer? We’ve seen it more than once before. Similar shape, similar attitude, its attention fixed on something in the grass near the foot of a tree, that can only be a squirrel. Looking it up later, I see that it’s a Vizsla, also known as a Hungarian Pointer. I stroll past it, resisting the impulse to give it some advice: you may be quick but you won’t win, they climb, you don’t. We’ve seen some close shaves for squirrels in the past but they always seem to evade dogs’ jaws. And ‘Bagpipe Music’? Pretty good, in fact. A slight hiccup over the penultimate stanza but both MacNeice and myself ending strongly:

It’s no go my honey love, it’s no go my poppet;

Work your hands from day to day, the winds will blow the profit.

The glass is falling hour by hour, the glass will fall for ever,

But if you break the bloody glass you won’t hold up the weather.

Now distractions range from the two old ladies intent on feeding a squirrel by hand (‘Come on, dear, see what I’ve got’ – Fleas, soon enough, I suspect) to the fellow with the ponytail and curious blue-green leggings intent on kicking a very small ball across the grass, and who crosses my path again half an hour later in a different and distant part of the park; and a murder of crows, around thirty in total, spread right across and down a broad grassy slope to the cycle path that runs along beneath the outspread branches of several wild pear trees. The fruits fall partly onto the earthy slopes beyond and partly onto the cycle path itself, one missed my right ear by inches one day last week. Walking along that path now before climbing sharply to my left, I see a dozen crows rooting among the fallen pears, though some turn to stare at me as I approach. ‘Are you auditioning for that nice Mister Hitchcock?’ I ask. One crow, not to be put off by a mere human, lingers to stick its beak straight through a pear before flying up to the branch above. Knowing how clever corvids are, I watch to see how it goes about extricating beak from fruit. It thrusts the pear into a narrow fork of branches which holds it in a tight embrace, withdraws the beak and starts tucking in. I whistle my sincere appreciation. That Lowellian mother skunk, I recall,

jabs her wedge-head in a cup

of sour cream, drops her ostrich tail,

and will not scare.

Why is it so hard these days? No answers on a postcard, please. At school, everyone learned poems by heart and some people never lost the habit. I recalled an aside of the Reverend Kilvert: ‘I thought of William Wordsworth the poet who often used to come and stay at this house with blind Mr. Monkhouse who had nearly all his poems off by heart.’[1] Eric Gill’s father and one of Gill’s teachers, named Mr Catt, were great admirers of Tennyson. Gill himself also learned much of it by heart, being particularly fond of ‘the passage about the routine of rural agriculture:

As year by year the labourer tills

His wonted glebe and lops the glades’[2]

This is from stanza CX of Tennyson’s In Memoriam A. H. H., the initials those of Tennyson’s beloved friend Arthur Henry Hallam, who died in Vienna in 1833. Born in 1811, he was eighteen months younger than Tennyson. They had met at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1828. Tennyson seems to have begun this long poem very soon after hearing of Hallam’s death, though it was not published until 1850, and then anonymously. Edward Fitzgerald—translator of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam—wrote to the poet’s elder brother Frederick Tennyson (15 August 1850): ‘Alfred has also published his Elegiacs on A. Hallam: these sell greatly: and will, I fear, raise a host of Elegiac scribblers.’[3]

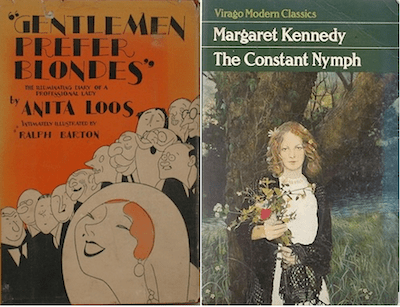

But it is not only poetry that the heroes of yesteryear committed to memory in large chunks – some mastered prose in a similar way, which always seems to me somehow an even more impressive achievement, though I accept that actors, having to learn their lines, sometimes comprising tremendously long speeches or monologues, would not necessarily find it so. Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Ford would swap pages of Flaubert or Maupassant, while James Joyce ‘knew by heart whole pages of Flaubert, Newman, de Quincey, E. Quinet, A. J. Balfour and of many others.’[4] And, while Anita Loos’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was apparently one of Patrick White’s favourite novels (Joyce, Faulkner and Edith Wharton were also admirers), he knew Margaret Kennedy’s The Constant Nymph ‘practically off by heart.’[5]

‘Heart’ is another of those words with a great many friends, the compounds running over several columns of the dictionary: in one’s mouth or boots or the right place; open, shut, taken; worn on the sleeve; piercing, rending, sore and sick. It has its reasons and is, in many contexts, simply mysterious, as the author of ‘Dover Beach’ wrote:

But often, in the world’s most crowded streets,

But often, in the din of strife,

There rises an unspeakable desire

After the knowledge of our buried life;

A thirst to spend our fire and restless force

In tracking out our true, original course;

A longing to inquire

Into the mystery of this heart which beats

So wild, so deep in us – to know

Whence our lives comes and where they go.[6]

I briefly consider this last poem as a candidate but coming in at around a hundred lines, it may be a stretch too far for me. Sonnets are a handy length, though . . .

Notes

[1] Francis Kilvert, entry for 27 April 1870, Kilvert’s Diary, edited by William Plomer (London: Jonathan Cape, 1938, reissued 1969), I, 119.

[2] Fiona MacCarthy, Eric Gill (London: Faber & Faber, 1990), 26.

[3] The Letters of Edward Fitzgerald, edited by Alfred McKinley Terhune and Annabelle Burdick Terhune, four volumes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980), I, 676.

[4] Frank Budgen, James Joyce and the Making of ‘Ulysses’ and other writings, enlarged edition (1934; London: Oxford University Press, 1972), 181. Edgar Quinet was a French historian; by A. J. Balfour is meant, presumably, the British Prime Minister (1902-1905) – who also published works of philosophy.

[5] David Marr, Patrick White: A Life (London: Vintage, 1992), 85.

[6] Matthew Arnold, ‘The Buried Life’, Poetry and Criticism of Matthew Arnold, edited by A. Dwight Culler (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1961), 114.