(Nicholas Condy, Estate Staff in a Servants’ Hall: Mount Edgcumbe House)

As we get older – I’m warily assuming that I’m not alone in this – our reading habits tend to change. These days, I don’t even pretend to persevere with a work that bores me or that I find incomprehensible, while avoiding anything that smacks of the dutiful. I also have a small store of things that keep the reading wheels turning if I stall. Crime fiction, certainly, but also a few writers with a healthy backlist of novels and stories, always of, or above, a certain quality threshold, literary but not excruciatingly so, tending to the concise and accessible. My usual suspects include Graham Greene and Muriel Spark.

Reading recently Spark’s unsettling short novel Not to Disturb, I came across Lister, the Baron Klopstock’s butler, saying to the other household servants as they anticipate the incursion of the press: ‘“Bear in mind that when dealing with the rich, the journalists are mainly interested in backstairs chatter. The popular glossy magazines have replaced the servants’ hall in modern society. Our position of privilege is unparalleled in history. The career of domestic service is the thing of the future.”’[1]

Any close encounters with literature and history, up to and well into the twentieth century will bump up against the servants – or, very often, the silence and spaces where the servants would be. If domestic service of the old kind seemed until recently to have largely died out in this country, except in the homes of the immensely rich or ostentatious, in many other parts of the world, it seems never to have diminished much at all. Definitions of ‘servant’ and ‘service’ have shifted or dissolved, and the contemporary situation is complex and frequently alarming, riven with cancelled visas, failed safeguards and government inaction, while the exploitation and abuse reported from a great many countries seem indistinguishable from slavery.

(John Finnie, Maids of All Work: Museum of the Home)

Lucy Lethbridge observed that: ‘In 1900 domestic service was the single largest occupation in Edwardian Britain: of the four million women in the British workforce, a million and a half worked as servants, a majority of them as single-handed maids in small households. Hardly surprising then that the keeping of servants was not necessarily considered an indication of wealth: for many families it was so unthinkable to be without servants that their presence was almost overlooked.’[2]

In Dorothy Sayers’ childhood, her biographer wrote, ‘It was the period of wash-stands with jug and basin in the bedrooms, and chamber pots. The housemaid carried cans of hot water up to the bedrooms every morning. When baths were needed, hot water was again carried up and poured into a hip bath. ‘“Strangely enough, my mother used to say,” wrote Dorothy, “she never had a servant complain of this colossal labour in all the twenty years we were at Bluntisham.”’[3] Beside this might be placed Rudyard Kipling’s recalling, late in life, his dislike for those radicals who ‘derided my poor little Gods of the East, and asserted that the British in India spent violent lives “oppressing” the Native. (This in a land where white girls of sixteen, at twelve or fourteen pounds per annum, hauled thirty and forty pounds weight of bath-water at a time up four flights of stairs!)’[4] Twelve or fourteen pounds. . . At a private view, on 3 December 1898, Arthur Balfour, who would become Prime Minister in 1902, bought two of William Hyde’s pictures on the spot. Hyde’s collaboration with the poet Alice Meynell, London Impressions, her ten essays complementing his many ‘etchings and pictures in photogravure’ was published that month, priced at eight guineas, apparently ‘equal to a house servant’s wages for a year’.[5]

Some servants were more highly prized—and individualised—particularly butlers and manservants. E. S. Turner informed his readers that: ‘The butler wore no livery but was attired in formal clothes, distinguished by some deliberate solecism—the wrong tie for the wrong coat or the wrong trousers—to prevent his being mistaken for a gentleman.’[6] Always best to be on the safe side. In the household of Edward and Georgiana Burne-Jones, ‘William, like all good butlers, was a depressive.’[7] Some butlers and valets had interesting family connections. In 1840, Benjamin-François Courvoisier was hanged outside Newgate Prison, before a huge crowd (among which were Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray), for the murder of Lord William Russell (he was suspected of other murders but never charged with them). The defendant’s legal representation was provided by Sir George Beaumont, the amateur painter, friend of William Wordsworth and art patron whose pictures were a foundational gift to the National Gallery. Beaumont’s butler was Courvoisier’s uncle.[8]

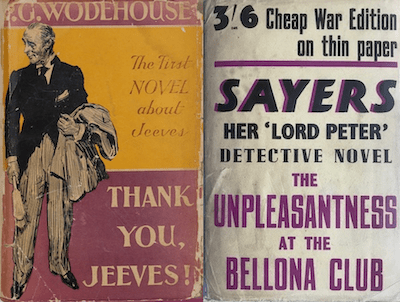

After the irruption of Sam Weller into the serial version of Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers and the contribution of Passepartout to Phineas Fogg’s trip Around the World in 80 Days, the most famous—and visible and audible—manservant, in or out of literature, is presumably Jeeves, Bertie Wooster’s valet, surely followed, if at a modest distance, by Lord Peter Wimsey’s ‘immaculate man’, Mervyn Bunter.[9] It’s been suggested that Bunter drew partly on P. G. Wodehouse’s creation though he certainly incorporated elements of a man named Bates, the ‘gentleman’s gentleman’ to an ex-cavalry officer, Charles Crichton, whom Sayers met in France; and Sayers’ husband, ‘Mac’ Fleming, who developed his own photographs and was a good cook (also Bunter attributes).[10] Bunter, Wimsey’s mother explains to Harriet Vane, was previously a footman but ended up a sergeant in Peter’s unit. They were together in a tight spot and took a fancy to each other – ‘so Peter promised Bunter that, if they both came out of the War alive, Bunter should come to him. . . .’ Wimsey’s nightmares about German sappers linger on for a few postwar years: he’s afraid to go to sleep and unable to give orders of any kind. ‘There were eighteen months . . . not that I suppose he’ll ever tell you about that, at least, if he does, then you’ll know he’s cured. . .’ In January 1919, Bunter turns up, on one of Wimsey’s worst days, takes charge and sees to everything, not least finding the Piccadilly flat and installing himself and Wimsey in it.[11]

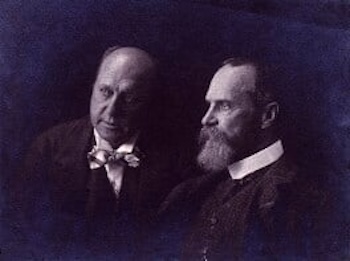

In that postwar period, apparently, ‘as many as forty ex-soldiers would answer a single advertisement for domestic help.’[12] Though the widespread employment of domestic servants hugely diminished by the time of the Second World War, the habit sometimes persisted in individual lives. Penelope Fitzgerald’s 1974 letter to her daughter Maria, describing the guests at the ‘surrealist tea-party’ that took place during her visit to a friend in Rye, includes mention of ‘Henry James’s manservant (still living in Rye, but with a deaf-aid which had to be plugged into the skirting) who couldn’t really bear to sit down and have tea, but kept springing up and trying to wait on people, with the result that he tripped over the cable and contributing in a loud, shrill voice remarks like “Mr Henry was a heavy man – nearly 16 stone – it was a job for him to push his bicycle uphill” – in the middle of all the other conversation wh: he couldn’t hear.’[13]

(Marie Leon, ‘Henry and William James’, (c) National Portrait Gallery)

It occurs to me at this late stage that the matter of servants is not purely an historical issue in my own case since, for three years in Singapore, my parents had the benefit of a cook-boy and an amah, Goh Heck Sin and his wife Leo: cooking, cleaning, laundry all taken care of (had there been young children in the family, the amah would have looked after them too). My primary—and certainly not undervalued—inheritance from those years is my ability to attract the attention of cats by making the call that Sin always made when he summoned our three (Thai Ming, Remo, Tiga) to their meals of rice and steamed fish.

Notes

[1] Muriel Spark, Not to Disturb (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1974), 83.

[2] Lucy Lethbridge, Servants: A Downstairs View of Twentieth-century Britain (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 9.

[3] Barbara Reynolds, Dorothy Sayers: Her Life and Soul, revised edition (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1998), 24. Sayers was born in 1893.

[4] Rudyard Kipling, Something of Myself, edited by Robert Hampson (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987), 87.

[5] Jerrold Northrop Moore, The Green Fuse: Pastoral Vision in English Art, 1820-2000 (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007), 90.

[6] E. S. Turner, What the Butler Saw: Two Hundred and Fifty Years of the Servant Problem (Michael Joseph 1962; reprinted with new afterword, London: Penguin Books, 2001), 158.

[7] Penelope Fitzgerald, Edward Burne-Jones (London: Michael Joseph, 1975), 223.

[8] Judith Flanders, The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern Crime (London: Harper Press, 2011), 202fn.

[9] Dorothy L. Sayers, ‘The Entertaining Episode of the Article in Question’, in Lord Peter Views the Body (1928; London: New English Library, 1977), 27.

[10] Reynolds, Dorothy L. Sayers, 112, 180.

[11] Dorothy L. Sayers, Busman’s Honeymoon,(1937; London: Coronet, 1988), 379-380.

[12] Turner, What the Butler Saw, 279.

[13] Penelope Fitzgerald, So I Have Thought of You: The Letters of Penelope Fitzgerald, edited by Terence Dooley (London: Fourth Estate, 2008), 150.