(John Milne Donald, Autumn Leaves: Glasgow Museums Resource Centre)

‘Darknesse and light divide the course of time, and oblivion shares with memory a great part even of our living beings; we slightly remember our felicities, and the smartest stroaks of affliction leave but short smart upon us.’[1]

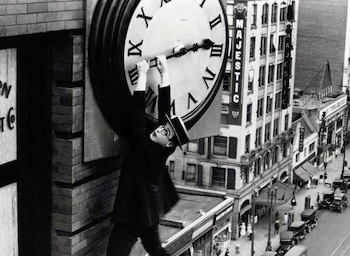

The leaves are falling faster now, perhaps mostly fallen. Our clocks have gone back an hour and we are on Greenwich Mean Time. The polymath Edward Heron-Allen wrote in his journal on 22 May 1916, ‘The notable feature of the month is the establishment by law on the 20th of “summer time” which Willett, the originator of the idea, never lived to see introduced. At midnight on the 20th we all had to put our clocks on one hour, and in this way an hour of daylight is “added” to the day.’ And, five months later, he noted: ‘I do not think I have recorded that on 30 September we put our clocks back an hour and returned to Greenwich time.’[2]

William Willett, whose 1907 pamphlet, The Waste of Daylight, marked a crucial point in the advance towards ‘summer time’, had died from influenza on 4 March 1915, at the early age of 58, and is buried in St Nicholas churchyard in Chislehurst (as is his second wife.) The 1916 emergency law was passed to change the clocks twice a year as a measure to reduce energy and increase war production. It became a permanent feature when the Summertime Act was passed in 1925.

Leaves falling, darker days, the year in some ways closing down – but all these are in the natural order of things, as—or so we hope—the political convulsions, atrocities in Gaza, Lebanon, Ukraine, Sudan and elsewhere, are not. At least, as Jake Barnes says, at the close of Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, ‘Isn’t it pretty to think so?’

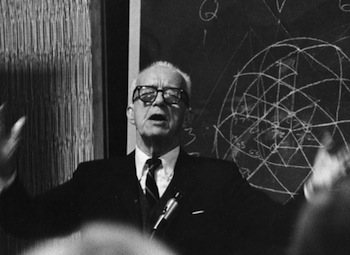

(John Berryman via The Paris Review)

‘Now there is further a difficulty with the light’, John Berryman wrote:

I am obliged to perform in complete darkness

operations of great delicacy

on my self.[3]

Currently those operations feature slow and sometimes painful analyses of my bafflement and confusion, not always helped by the Librarian’s daily bulletins from the battlefield that is the American election, often delivered in tones of appalled astonishment, while the phrase ‘batshit crazy!’ tends to recur.

What, in some senses, seems self-evident (one candidate sane, the other rather less so) is dwarfed by complexities and nuances almost invisible to us – we’re here and they’re. . . over there. I grasp, more or less, the fact that America is so divided a country now that neither side can—perhaps has no wish to—hear the other. But there is that other complication. While I can see that the appalling and spineless response of the Biden government to the conflict in the Middle East must repel a good many voters, it baffles me that those voters should think that withholding their vote from Harris (and thereby potentially contributing to her defeat) could somehow help the Palestinian people. Surely the precise opposite?

(John Donne, unknown English artist, c.1595)

Well, we’ll know soon enough. People, eh? I think of Katherine Rundell writing that, ‘amid all Donne’s reinventions, there was a constant running though his life and work: he remained steadfast in his belief that we, humans, are at once a catastrophe and a miracle.’ And: ‘He thought often of sin, and miserable failure, and suicide. He believed us unique in our capacity to ruin ourselves. “Nothing but man, of all envenomed things,/Doth work upon itself with inborn sting”. He was a man who walked so often in darkness that it became for him a daily commute.’[4]

Notes

[1] Sir Thomas Browne. Hydriotaphia, or Urn-Buriall, in Selected Writings, edited by Geoffrey Keynes (London: Faber and Faber, 1970), 152.

[2] Edward Heron-Allen’s Journal of the Great War: From Sussex Shore to Flanders Fields, edited by Brian W. Harvey and Carol Fitzgerald (Lewes: Sussex Record Society, 2002), 65, 71.

[3] John Berryman, ‘Dream Song # 67’, The Dream Songs, collected edition (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1969), 74.

[4] Katherine Rundell, Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne (London: Faber, 2023), 5-7.