(Selwyn Image, ‘Stained Glass Design’, 1887: © Victoria & Albert Museum)

Looking at the news this 4 August, it’s sobering to reflect that one of the candidates for the Tory leadership recently vowed to ‘turn the tide of Liberalism’, when it is painfully obvious that what is actually – and urgently – needed is to turn the tide of fascism and racist violence.

Today is the 110th anniversary of Britain’s declaration of war, which will be old news to anyone who reads or writes around the First World War, or simply has an average grasp of history, and it has tended rather to dwarf other, personal, events and anniversaries – though not, perhaps, for the individuals concerned.

Walter de la Mare (‘Jack’) and Elfrida Ingpen (‘Elfie’) were married privately in the parish church at Battersea on 4 August 1899. D. H. Lawrence’s sister Ada married William Edward Clarke on 4 August 1913.[1] Julian Barnes noted that his grandparents were married on 4 August 1914, the day itself,[2] which also marked the birth of Anthony, Rebecca West’s son by H. G. Wells. It was the birthday of Florence, Stanley Spencer’s sister: she married J. M. Image, Cambridge don and brother to Selwyn Image.[3] Ezra Pound, quite recently arrived in London, went in February 1909 to see Selwyn, ‘who does stained glass. & has writ a book of poems. & was one of the gang with Dowson – Jonson – Symons – Yeats etc. – talks of “when ‘old Verlaine’ came over etc.’[4]

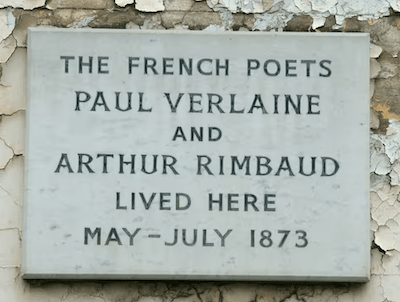

(Plaque, Royal College Street, Camden, via The Guardian: photograph by Frank Baron)

‘Old Verlaine’ came over more than once, firstly in 1872, in the company of Arthur Rimbaud (whom he later shot and wounded, in Brussels, another story), settling for a while in rooms in Howland Street off the Tottenham Court Road and, on a second visit shortly afterwards, in Camden Town. They seem to have dropped in on one of the soirées at the Fitzroy Square home of Ford’s maternal grandfather, the painter Ford Madox Brown and his second wife Emma.[5] In October 1893, at the suggestion of William Rothenstein, Verlaine arrived to lecture and read his poetry, in London and in Oxford. Ernest Dowson recorded that, arriving in the small hours of the morning, Verlaine was greeted by the poet and critic Arthur Symons, ‘bearing a packet of biscuits and a bottle of gin’. He gave his first lecture at Barnard’s Inn on 21 November and two days later arrived in Oxford, to be met by Rothenstein and a man named York Powell, of Christ Church (Icelandic scholar, authority on Roman Law, boxing and Middle High Dutch. He also knew Hebrew and Old Irish). Verlaine lectured on contemporary French poetry ‘in the room behind Mr Blackwell’s shop’ and was so enamoured of the city—‘Ô toi, cité charmante et mémorable, Oxford!’— that prising him out of it necessitated both escorting him to the train and withholding his lecture fee until he was safely on the train for London.[6]

Famously (if not quite famously enough), 4 August is the date threaded through Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier—seventeen occurrences in all—and also the birthdate (4 August 1841) of W. H. Hudson, one of Ford’s most consistently admired writers, to whose work he recurred over more than thirty years, sometimes singling out Nature in Downland but more generally stressing that Hudson’s writing had ‘a tranquillity, a clearness of epithet, and an utter absence of affectation or strain that renders his pages like balm for tired souls’, adding that, as with Turgenev, ‘it is all one whether these writers treat of birds or of South American revolutions, of peasants singing, or of Nihilists at their debates. It is simply that the pages of their books reveal a personality, restful soothing, and itself quite at ease.’[7]

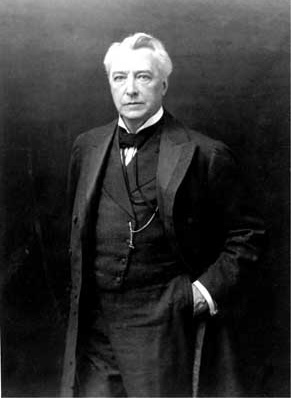

(Edward Heron-Allen in 1927, via The Edward Heron-Allen Society)

On 4 August 1918, the polymath (writer, scientist, linguist, historian) Edward Heron-Allen—very much not a friend of Ford’s—wrote in his journal that: ‘One thing stands out and is certain, and that is, that mentally and physically we are changed, changed as we never dreamed a whole nation could be changed.’ He noted that he had ‘escaped the “Spanish Influenza” of which we hear so much, but it seems to be a real menace. We are told that the German Army is “decimated” by it, and that this accounts for the delay and failure’ of the recent offensive.[8]

A decade and a bit further on, the poet and artist David Jones was making his third visit to his friend Helen Sutherland at Rock Hall, Northumberland, 4 August 1931. At the start and end of each visit, Jones would be driven past the Duke of Northumberland’s castle. Helen told him that this was on the site of Lancelot’s castle, Joyous Guard – and the supposed place of his burial. ‘With this association in mind, Jones referred to the church at Rock as “the Chapel Perilous”, the place of terrifying enchantment that Lancelot enters – an episode in Malory that reminded him of his experience at night in Mametz Wood.’[9]

The Battle of Mametz Wood, during the First Battle of the Somme, involved British attacks on 7 and 10-12 July, centrally involving the 38th (Welsh) Division and resulting in huge losses: their casualties were one-fifth of their total strength. David Jones was wounded in the early hours of 11 July, and his great poem In Parenthesis, stops at that point.[10]

(David Jones via The Poetry Foundation)

Lie still under the oak

next to the Jerry

and Sergeant Jerry Coke.

The feet of the reserves going up tread level with your fore-

head; and no word for you; they whisper one with another;

pass on, inward;

these latest succours:

green Kimmerii to bear up the war.[11]

Ford Madox Ford left Cardiff with the 3rd Battalion on 13 July; and departed for France from Waterloo on 17 July. When 4 August came around this time, he was in a Casualty Clearing Station at Corbie, having been blown into the air and severely concussed by a high explosive shell, ‘so that, as I have said, three weeks of my life are completely dead to me though I seem to have gone about my duties as usual. But, by the first of September I had managed to remember at least my own name…’[12]

Quite a few public figures (not least newspaper columnists) seem to have lost their memories lately – quite selectively and with markedly less excuse.

Notes

[1] Letters of D. H. Lawrence II, June 1913–October 1916, edited by George J. Zytaruk and James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 38n.

[2] Julian Barnes, Nothing to be Frightened of (Cape 2008), 28.

[3] Kenneth Pople, Stanley Spencer: A Biography (London: Harper Collins, 1991), 55, 49.

[4] Ezra Pound to His Parents: Letters 1895–1929, edited by Mary de Rachewiltz, David Moody and Joanna Moody (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 160.

[5] Angela Thirlwell, Into the Frame: The Four Loves of Ford Madox Brown (London: Chatto & Windus, 2010), 100. On a later visit, Verlaine lodged at 10, London Street, Fitzroy Square, very close to Howland Street.

[6] Joanna Richardson, ‘’The English Connection: French Writers and England, 1800-1900’, in Richard Faber, editor, Essays by Divers Hands: being the transactions of the Royal Society of Literature. New Series: Volume XLV (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1988), 33-35; Joanna Richardson, Verlaine (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1971), 317-320.

[7] Ford Madox Ford, ‘Literary Portraits: XXV. The Face of the Country’, Tribune (11 January 1908), 2.

[8] Edward Heron-Allen’s Journal of the Great War: From Sussex Shore to Flanders Fields, edited by Brian W. Harvey and Carol Fitzgerald (Lewes: Sussex Record Society, 2002), 203. A footnote adds that there were approximately 70 million deaths worldwide in 1918-19, compared to the estimated total of 7.8 million killed in action in the war.

[9] Thomas Dilworth, David Jones: Engraver, Soldier, Painter, Poet (London: Jonathan Cape, 2017), 140-142.

[10] Anthony Hyne, David Jones: A Fusilier at the Front (Bridgend: Seren Books 1995), 37.

[11] David Jones, In Parenthesis (1937; London: Faber, 1963), 187.

[12] Ford Madox Ford, It Was the Nightingale (London: Heinemann, 1934), 175.