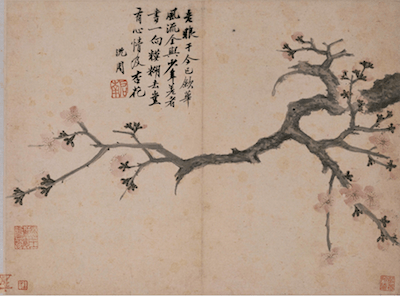

The year turns to meteorological spring. Blue sky, crisp air, early blossom, some trees apparently having had advance warning of this.

‘A glimmer of light’, the Librarian observed of the news that the Green party’s Hannah Spencer had won the Gorton and Denton by-election convincingly, followed by predictable slurs from the bad losers and incontinent frothings from the right-wing tabloids. Certainly a glimmer, though seemingly not reaching the relevant offices of the Labour administration, where it would surely have made even more legible the message that the government has been heading in precisely the wrong direction.

Snuffing that candle, though, was news that the President of the United States had been played again, and that the inevitable chaos, destruction and slaughter of civilians was already well underway – again.

Earlier, the most recent stories were all of fallen or ruined princes, royal, self-styled and otherwise. We no longer execute royal personages who have fallen from favour, not since 30 January 1649 anyway. In this country, the last official execution of anyone was in 1964, when, at 08:00 on 13 August, two convicted murderers were hanged simultaneously, one at Liverpool’s Walton prison and the other at Strangeways prison in Manchester. Nearer in time to the demise of Charles I outside the Banqueting House, Whitehall, though, public hangings were both frequent and popular, Samuel Pepys and James Boswell among those attending. ‘There were often as many as 30,000 people; one hanging in Moorfields in 1767 attracted 80,000 spectators.’[1]

Princes in a bad way might prompt in some bookish people a memory of the only line they can confidently ascribe to the poet and travel writer Gérard de Nerval. His ‘El Desdichado’, one of the ‘Chimeras’, begins:

Je suis le ténébreux, – le veuf, – l’inconsolé,

Le prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie

Richard Sieburth’s translation has:

I am the man of gloom – the widower – the unconsoled,

the prince of Aquitaine, his tower in ruins[2]

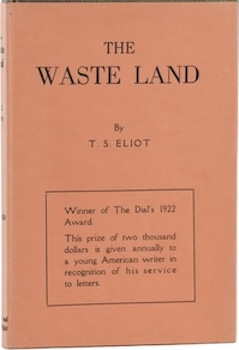

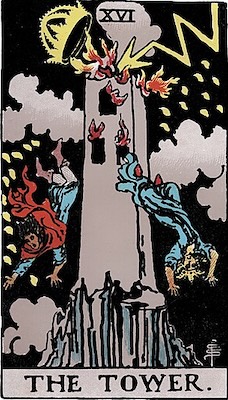

That second line in French is the one made famous by T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. One of that poem’s celebrated notes offers for line 429 only the name of the poet and the title of the poem. But an earlier note (to line 46) states that Eliot is ‘not familiar with the exact constitution of the Tarot pack of cards, from which I have obviously departed to suit my own convenience.’ He mentions The Hanged Man (one of the major arcana), The Phoenician Sailor (not a card in the traditional pack), The Merchant (a suit in the minor arcana), The Man with Three Staves (I’ll take a stab at the three of Wands). Oddly, he doesn’t mention The Tower (XVI: also one of the major arcana): the Prince’s is certainly in pretty bad shape and I gather (not being familiar myself with the exact constitution of the Tarot pack, as must be glaringly apparent) that the Tower (upright) is really not a card you want to come up against, connoting as it does chaos and destruction – even reversed, it’s not the ideal companion for an evening.

Princes and towers come unpleasantly together in a familiar, yet still unresolved, episode in English history, Richard of Shrewsbury and his brother, the young Edward V, who went in to the Tower of London but never emerged again. Two likely skeletons turned up during renovations in 1674. Richard III is often named as their murderer though it’s sometimes suggested that Henry VII has a case to answer.

A. E. Waite’s Pictorial Guide to the Tarot was published in 1910 (following the issue of the Rider-Waite Tarot deck, illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith) and reprinted in 1922, the year that The Waste Land also appeared. The illustration of the Tower shows it struck by lightning, a crown knocked off its top and two falling figures.

If not explicitly in the form of the Tarot card, Eliot’s poem has its towers too.

The brisk swell

Rippled both shores

Southwest wind

Carried down stream

The peal of bells

White towers

Also:

Falling towers

Jerusalem Athens Alexandria

Vienna London

Unreal

A few lines on:

And upside down in air were towers

Tolling reminiscent bells, that kept the hours

And voices singing out of empty cisterns and exhausted wells.

The Waste Land sometimes appears unsettlingly prophetic, when we read back into it later follies, failures and fiascos. Not too prophetic this time around, let’s hope.

Notes

[1] Lucy Moore, The Thieves’ Opera: The Remarkable Lives and Deaths of Jonathan Wild, Thief-Taker, and Jack Sheppard, House-Breaker (London: Penguin Books, 1998), 220. A figure outstripped by a good many recent football crowds in both England and Scotland but the current population is nearly ten times what it was then.

[2] Gérard de Nerval, Selected Writings, translated with an introduction by Richard Sieburth (London: Penguin Books, 1999), 363.