This is the farmer sowing his corn,

That kept the cock that crowed in the morn,

That waked the priest all shaven and shorn,

That married the man all tattered and torn,

That kissed the maiden all forlorn,

That milked the cow with the crumpled horn,

That tossed the dog,

That worried the cat,

That killed the rat,

That ate the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built.

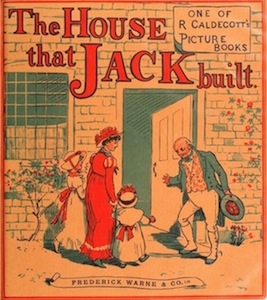

The accumulative rhyme, ‘The House That Jack Built’ was first published in a 1755 collection, Nurse Truelove’s New-Year’s-Gift: or, The Book of Books for Children. It has ‘probably been more parodied than any other nursery story’, in politics and advertising: but also in literature.[1]

In Canto XVII of Autumn Sequel (1954), Louis MacNeice writes: ‘The reasons and the rhymes/ Of Mother Church and Mother Goose have grown/ Equally useless since we have grown up/ And learnt to call our minds (if minds they are) our own’. Mother Goose might have found something oddly familiar in MacNeice’s later ‘Château Jackson’, included in The Burning Perch (1963) and beginning:

Where is the Jack that built the house

That housed the folk that tilled the field

That filled the bags that brimmed the mill

That ground the floor that browned the bread

That fed the serfs that scrubbed the floors

That wore the mats that kissed the feet

That bore the bums that raised the heads

That raised the eyes that eyed the glass

That sold the pass that linked the lands. . .[2]

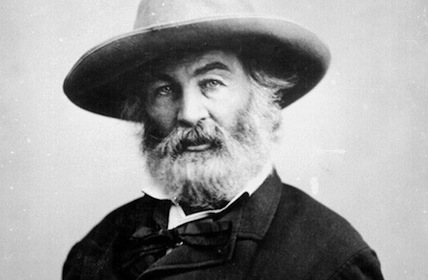

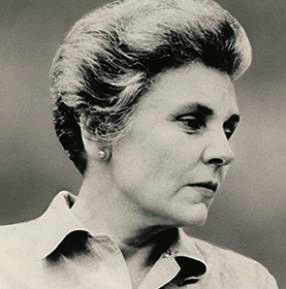

https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/elizabeth-bishop

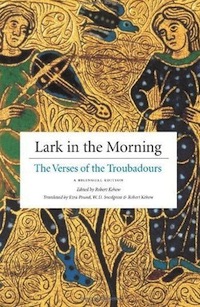

Fifteen years earlier, Elizabeth Bishop had visited Ezra Pound in St Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, where Pound had been confined since being found unfit to plead on charges of treason. Bishop was introduced to Pound by Robert Lowell and later, when serving as poetry consultant to the Library of Congress, visited Pound—who called her ‘Liz Bish’, a name she much disliked—regularly.[3]

First published in 1956 but dated by Bishop as 1950, her remarkable poem ‘Visits to St Elizabeths’ begins with an instantly recognisable rhythm and form:

This is the house of Bedlam.

This is the man

that lies in the house of Bedlam.

Its final stanza—it’s a poem of 78 lines—runs:

This is the soldier home from the war.

These are the years and the walls and the door

that shut on a boy that pats the floor

to see if the world is round or flat.

This is a Jew in a newspaper hat

that dances carefully down the ward,

walking the plank of a coffin board

with the crazy sailor

that shows his watch that tells the time

of the wretched man

that lies in the house of Bedlam.[4]

Though Bishop referred to this more than once as her ‘Pound poem’,[5] she told Anne Stevenson that ‘the characters are based on the other inmates of St. E[lizabeth]’s [ . . . ] One boy used to show us his watch, another patted the floor, etc.—but naturally it’s a mixture of fact and fancy.’[6]

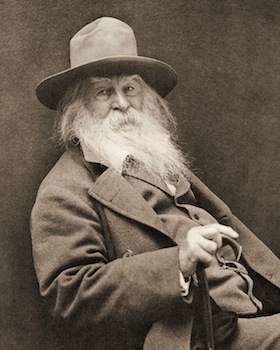

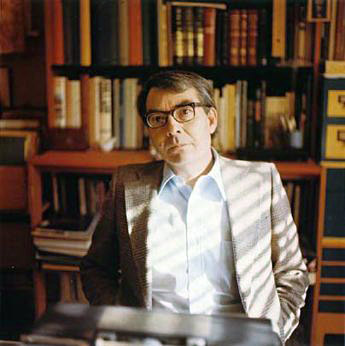

In the course of one of his most brilliant essays, ‘The House That Jack Built’, first given as a paper to inaugurate the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library’s Center for the Study of Ezra Pound and His Contemporaries on 30 October 1975 (it would have been Pound’s ninetieth birthday but he had died three years earlier), Guy Davenport begins by recreating John Ruskin’s writing of Letter XXIII of Fors Clavigera, almost exactly one hundred years before Pound’s death. The letter is indeed dated 24 October 1872.[7]

Photo credit: David Driscoll: http://beinecke.library.yale.edu/collections

Davenport describes Fors as ‘a kind of Victorian prose Cantos’, but his interest in that particular letter is indicated by Ruskin’s title: ‘The Labyrinth’ and perhaps the footnote, which reads: ‘A rejected title for this letter was “The House that Jack Built”’. Ruskin writes about ‘the great Athenian squire’, Theseus, among much else, before reaching the cathedral door at Lucca, on which are engraved several Latin sentences, many centuries old, which Ruskin translates as: ‘This is the labyrinth which the Cretan Dedalus built, out of which nobody could get who was inside, except Theseus: nor could he have done it, unless he had been helped with a thread by Adriane, all for love’. And that statement, ‘This is the labyrinth which the Cretan Dedalus built’, can, Ruskin says, be reduced from medieval sublimity to the rather more popular ‘This is the House that Jack Built’. He analyses the symbols, considers coins, justice and other matter ‘until he can triumphantly identify the Minotaur with greed, lust, and usury’. At one point, Davenport observes that Ruskin ‘is just getting warmed up’.[8]

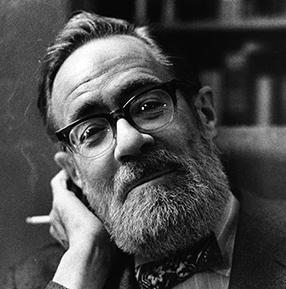

The same might be said of Davenport, who will, in the course of the remainder of the essay, range over Olson, Joyce, Ovid, William Carlos Williams, Pavel Tchelitchew, Zukofsky, Leonardo da Vinci, Henri Rousseau, Picasso, Apollinaire, Brancusi, Michael Ayrton (maker of labyrinths), Wilbur Wright and others: but mainly Ezra Pound. Davenport is one of the most acute readers of Pound. One of the others, Hugh Kenner, concluded his magisterial The Pound Era with the statement that ‘Thought is a labyrinth.’[9] Indeed.

(Guy Davenport by Jonathan Williams, via Jacket magazine:

http://jacketmagazine.com/38/jwb01-davenport.shtml)

A labyrinth is certainly one in which we may be hopelessly and helplessly lost, sometimes unsure of whether we have passed this way before or even repeatedly – unless we have a thread. ‘All for love.’ Love is a good thread, undoubtedly. And there are others.

Davenport writes at one point of the frescoes in the Palazzo Schifanoia, painted for the Este family. Yeats once recalled Pound’s telling him that the frescoes had provided a basic outline for the scheme of his epic poem. Davenport continues: ‘The Cantos do indeed follow the triumphs, the seasons, and the activities of the seasons. To know the triumphs we must know the past, which is told in many tongues in many places; to know the past we descend, like Odysseus, into the House of Hades and give the blood of our attention (as translators, historians, poets) so that the dead may speak. To know the seasons we must understand metamorphosis, for things are never still, and never wear the same mask from age to age. The contemporary is without meaning while it is happening: it is a vortex, a whirlpool of action. It is a labyrinth.’ And he concludes that ‘The clue to this labyrinth, Pound knew, was history.’[10]

‘Labyrinthine’ might mean complex or endless, perhaps needlessly convoluted. Coleridge referred to De Quincey’s mind as ‘at once systematic and labyrinthine’.[11] Yeats wrote that : ‘A man in his own secret meditation / Is lost among the labyrinth that he has made / In art or politics’.[12] But it can be a point of focus, a positive necessity. The novelist Nicholas Mosley writes: ‘The idea that to make sense of one’s life one has to tell of the bad things as well as the good at least to oneself is at the back of much of this story: without a recognition of darkness as well as light there is no pattern; without pattern there is no chance of glimpsing a path through the maze. And without this what is the point of life, what is its wonder?’[13]

Yes.

References

[1] See The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, edited by Iona and Peter Opie (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 229-232.

[2] Louis MacNeice, Collected Poems, edited by Peter McDonald (London: Faber and Faber, 2007), 448-449, 580.

[3] Brett C. Millier, Elizabeth Bishop: Life and the Memory of It (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 199, 220.

[4] Elizabeth Bishop, Poems, Prose, and Letters, edited by Robert Giroux and Lloyd Schwartz (New York: Library of America, 2008), 127-129.

[5] Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell, edited by Thomas Travisano with Saskia Hamilton (London: Faber and Faber, 2008), 201, 345.

[6] Bishop, Poems, Prose, and Letters, 853.

[7] ‘Letter 23. The Labyrinth’: Fors Clavigera, II, 394. The Ruskin Library and Research Centre at Lancaster University has digitized and made generally available the monumental 39-volume Cook and Wedderburn edition (1903-1912) of the Works of John Ruskin. A stupendous project, wonderfully achieved: http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/depts/ruskinlib/Pages/Works.html

[8] Guy Davenport, The Geography of the Imagination (London: Picador, 1984), 45-47.

[9] Hugh Kenner, The Pound Era (London: Faber, 1972), 561.

[10] Davenport, The Geography of the Imagination, 56.

[11] Collected Letters of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, III: 1807-1814, edited by E. L. Griggs (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959), 205, quoted by Alethea Hayter, Opium and the Romantic Imagination (London: Faber and Faber, 1971), 234.

[12] W. B. Yeats, ‘Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen’, Collected Poems, second edition (London: Macmillan, 1950), 235.

[13] Nicholas Mosley, Efforts at Truth: An Autobiography (London: Minerva, 1996), 187.