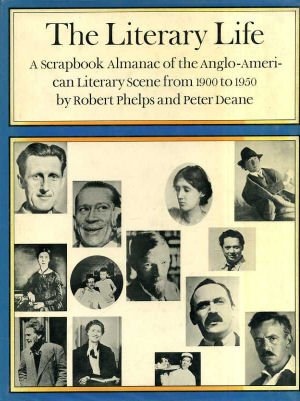

Browsing the tirelessly interesting The Literary Life: A Scrapbook Almanac of the Anglo-American Literary Scene from 1900 to 1950, I come across (‘In the Wings’ section of 1913): ‘“Eager for any sort of adventure,” Joyce Cary serves as a cook in the Montenegrin Army in the First Balkan War, receiving a gold medal for his participation in the final campaign.’[1] Montenegro! It reminded me that F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Major Jay Gatsby had been decorated by every Allied government, ‘even Montenegro, little Montenegro down on the Adriatic Sea!’[2]

And a cook! Intriguing, especially when poking about in various sources to confirm it but coming up against Red Cross nurse, stretcher bearer, Red Cross orderly, and finally: stretcher bearer and cook, which I promptly accept as definitive.

Cary (1888-1957) was born in Derry but, when he settled in England, this was where he largely stayed. He attended Clifton College in Bristol (as did L. P. Hartley, Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, Henry Newbolt, Geoffrey Household, Montague Summers, actors, musicians and an astonishing array of military, scientific and political notables). He joined the colonial service in Africa and fought in the First World War – with a Nigerian regiment in the Cameroon campaign. He seems to have largely dropped from view but was pretty well-known for a while, particularly for his novel The Horse’s Mouth, published in 1944 and reprinted as a Penguin book four years later.

(Alec Guinness and Kay Walsh in the 1958 film, The Horse’s Mouth)

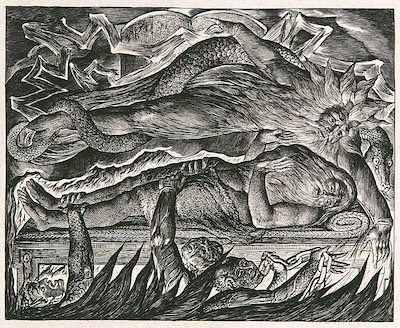

I did read several of his other novels but that’s the one I remember best. It’s about a painter, Gulley Jimson, who has some diverting comments about the art that he practises. One day, he remembers, ‘I happened to see a Manet. Because some chaps were laughing at it. And it gave me the shock of my life. Like a flash of lightning. It skinned my eyes for me and when I came out I was a different man. And I saw the world again, the world of colour. By Gee and Jay, I said, I was dead, and I didn’t know it.’ A little later, ‘And then I began to make a few little pencil sketches, studies, and I took Blake’s Job drawings out of somebody’s bookshelf and peeped into them and shut them up again. Like a chap who’s fallen down the cellar steps and knocked his skull in and opens a window too quick, on something too big.’ But to a boy who keeps turning up, saying he wants to be a painter himself, Jimson tells him ‘“something for your good. All art is bad, but modern art is the worst. Just like the influenza. The newer it is, the more dangerous. And modern art is not only a public danger – it’s insidious. You never know what may happen when it’s got loose.”’[3]

(William Blake, engraving for The Book of Job)

Cookery and war, though. Conflict in the kitchen is familiar fare in several strenuous television series of recent years but there are other offscreen instances enough.

Joan Didion recalled being taught to cook by someone from Louisiana. ‘We lived together for some years, and I think we most fully understood each other when once I tried to kill him with a kitchen knife.’[4] And M. F. K. Fisher remembered a Mrs Cheever at Miss Huntingdon’s School for Girls: ‘She ran her kitchens with such skill that in spite of ordinary domestic troubles like flooded basements and soured cream, and even an occasional extraordinary thing like the double murder and hara-kiri committed by the head boy one Good Friday, our meals were never late and never bad.’[5]

In the First World War, as in so many other wars, cookhouses and dining halls were central to the military effort, both at home and abroad. If your medical category was C1, then cookhouse fatigues were likely to feature on your work rota, along with clerking, cleaning and gardening. The poet F. S. Flint did precisely that although towards the end of his war service in England and Scotland—brief enough since he was only called up in August 1918—he taught French to officers who were awaiting demobilisation. The novelist Edgar Jepson wrote of attempting ‘to diminish the gluttony of the British people.’ His masterpiece drew, he said, on the experiments of Mrs Peel in the basement kitchen: ‘I dwell at this length on the Cookery Book [The Win the War Cookery Book of May 1917] because I wish to make it wholly clear that it shares equally with the United States the glory of having won the war.’ He added: ‘Not that I would have it supposed that I reckon the months I spent at the Ministry of Food wasted: I acquired there a faith in human stupidity, which nothing will ever shake.’[6]

(Eugène Louis Bourdin, Étaples)

Closer to the scenes of combat, the young Wilfred Owen would discover in December 1916 that meals in the officers’ mess at Étaples in northern France—where a series of mutinies the following year resulted in executions and prison sentences—‘were cooked by a former chef to the Duke of Connaught and presided over by a baronet.’[7]

Midway through that war, in the same year as Owen’s sumptuous dinners, poet and novelist Robert Graves bought a small cottage from his mother. He wrote, a decade later: ‘I bought it in defiance of the war, as something to look forward to when the guns stopped (“when the guns stop” was how we always thought of the end of the war). I whitewashed the cottage and put in a table, a chair, a bed and a few dishes and cooking utensils. I had decided to live there by myself on bread and butter, bacon and eggs, lettuce in season, cabbage and coffee; and to write poetry.’[8]

War and the kitchen. Really not in my case; perhaps the nearest would be peeling a butternut squash, the culinary equivalent, I suppose, of fell walking or hill climbing, requiring as it does both stamina and occasional brute strength. And war has changed out of all recognition in the last hundred-odd years, sometimes seeming to be called ‘war’ only to spare the feelings of those on one side who are slaughtering, almost without resistance or effective means of defence, the other. And there was a time, after all, when ‘war’ meant men on horseback. . .

‘It was from the cavalry that the nation’s military leaders were drawn. They believed in the cavalry charge as they believed in the Church of England.’ Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, when the future General Sir Ian Hamilton, as an English observer in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, reported that ‘the only thing the cavalry could do in the face of entrenched machine guns was to cook rice for the infantry’, his statement had the effect of ‘causing the War Office to wonder if his months in the Orient had not affected his mind.’[9]

Never underestimate the value to the world of getting the cooking time of your rice just right.

Notes

[1] Robert Phelps and Peter Deane, The Literary Life: A Scrapbook Almanac of the Anglo-American Literary Scene from 1900 to 1950 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1968), 54.

[2] F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1926; edited by Tony Tanner, London: Penguin Books, 2000), 65.

[3] Joyce Cary, The Horse’s Mouth (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1948), 70-71, 72, 24-25.

[4] Joan Didion, South and West: From a Notebook, foreword by Nathaniel Rich (London: Fourth Estate, 2017), 8.

[5] M. F. K. Fisher, ‘The First Oyster’ (1924), in Gastronomical Me (1943; London: Daunt Books, 2017), 26.

[6] Edgar Jepson, Memories of an Edwardian and Neo-Georgian (London: Richards, 1937), 193, 196. Mrs C. S. Peel was a prolific author of books about thrifty cookery, including The Eat-Less-Meat Book: War Ration Housekeeping (1917).

[7] Dominic Hibberd, Wilfred Owen: A New Biography (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2002), 203.

[8] Robert Graves, Good-bye to All That: An Autobiography (1929; Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2014), 252.

[9] Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August and The Proud Tower, edited by Margaret MacMillan (New York: Library of America, 2012), 593, 214.