05:30 on the morning of another named storm, wind gusting like a fanatic and the tall, elaborate scaffolding at a house behind us, and three doors along, grinds and clacks and shrieks. It seems impossible that so much noise can result in no hazardous movement, no damage, no change in look or structure. And yet – collapsed scaffolding would be so absurdly appropriate, so ridiculously, symbolically pitch perfect, that I could never have taken either weather or metalwork seriously again.

Earlier this month, having avoided the news for the previous week, I’d lost track of the days, until I was walking away from coffee with my elder daughter and, halfway along the harbourside path, heard behind me the strains of a piper playing A Long Way To Tipperary. Armistice Day. A lengthy history but feeling a little awry when the world is so excessively out of true. Veterans of one world war utterly gone, veterans of the other all but gone. And, thinking of what the Second World War is believed to have been fought against, and of victory declared, and to look around the world now is. . . a little odd.

The good stuff is elsewhere. Indeed, the Decline of the West, though accelerating madly in recent months, seems oddly absent in West Sussex, where we go to spend a few days in Chichester for the Librarian’s birthday.

A quick shopping trip. What do we need? Wine and . . . something or other to go with it. And here is the Cathedral Close, Canon Lane, the Bishop’s Palace, St Richard’s Walk and the Deanery, which dates from 1725 and was itself a replacement for an earlier building, damaged in 1642, during the English Civil War. Key in the code and close the door and take in a roomy and well-appointed apartment with, unignorably, a television four or five times the size we’re used to. Could anything make the current dramatisation of Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light even more remarkable? Apparently so.

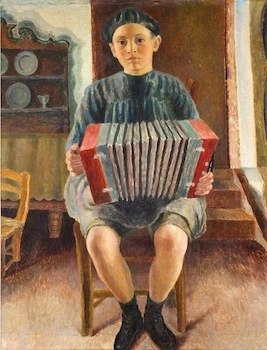

An excellent Carrington exhibition at the Pallant House Gallery: I’ve seen the Lytton Strachey portrait before but am convinced now that his fingers grow even more elongated under cover of darkness. The drawing of her brother is perfect; and the two portraits of Annie Stiles, seen together, are hugely pleasing. A scattering of works by Mark Gertler too, a significant presence in Carrington’s life, both personally and professionally: they include the portrait of Gilbert Cannan and His Mill, familiar from several visits to the Ashmolean in Oxford. Somehow, it strikes me as a little odder every time I see it. A few steps away from the building where we’re staying, we find an arresting anthology of birds, curious plants and extraordinary trees in the Bishop’s Palace Garden. Then a walk, nearly one and a half miles, following the surviving city walls, some traceable to the 3rd century. A bus trip to Selsey. And the Cathedral.

(Sutherland, Noli me Tangere and the Marc Chagall window)

‘I can stand a great deal of gold’, Henry James murmured to Desmond MacCarthy, as they stood in an exceptionally gilded drawing-room.[1] I can, it seems, stand a great deal of cathedrals. Poised on that delicate boundary between agnostic and atheist (finding it ultimately as absurd to state dogmatically that there isn’t as to state dogmatically that there is), I may attend evensong too (we did, liking to be sung to), though declining to recite the Apostle’s Creed, for obvious reasons.

But the Cathedral. I’ve been to Durham, Wells, Exeter, Salisbury, Christchurch, St Paul’s, Hereford, Bristol. Different settings, different grandeurs. Here—among much else, stained-glass windows, statuary, painted panels, altarpieces—is Graham Sutherland’s Noli me Tangere, and two huge tapestries, one by John Piper and the other co-created by Ursula Benker-Schirmer and West Dean College students. There is a stunning Marc Chagall window, installed in 1978, and Gustav Holst’s ashes are buried in the North Transept.

Then Selsey: the Ford Madox Ford connection, of course, Violet Hunt having rented a cottage from Edward Heron-Allen, she and Ford spending much time there before—and during—the war. Little of that remaining in Selsey – but fascinating to learn that the monastery here, founded by St Wilfrid in 681, became the first cathedral in Sussex, until 1076, when the see of Chichester was established.

On the morning we leave: snow. Knowing how bad we continue to be in this country at dealing with any weather event out of the ordinary—even thought the formerly extraordinary is increasingly now the unremarkable—we skip brunch in the Cloisters café and head for the station. And yes, trains cancelled, delayed, signal failures, the whole nine yards, as our American cousins say – to whom we warily extend our sympathy (amidst our total and enduring bafflement). . .

Notes

[1] Leon Edel, The Life of Henry James: Volume 2 (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1977), 680-681.