On 25 August 1773, in an indifferent inn at Banff, James Boswell watched Samuel Johnson pen a long letter to Mrs Thrale. ‘I wondered to see him write so much so easily. He verified his own doctrine that “a man may always write when he will set himself doggedly to it.”’[1]

Dogged, yes: ‘sullen’ I don’t quite see but ‘pertinacious’, holding obstinately to an opinion or a purpose, unyielding, we can certainly settle for. So that

Writing of April in the Scotland uplands, of mainly grey days, cold and snow, the 20-year-old John Buchan remarked: ‘Nor have we any of the common associations of spring, like the singing of birds. A mavis or a blackbird may on occasion break into a few notes, and there is, for certain, an increasing twitter among the trees. But the clear note of the lark as yet is not; the linnet does not pipe; the many named finches are still silent.’[2]

We have also been in the hills this April, though further south, with not a hint of snow. A few days in the Black Mountains, the border country, with its panoramic vistas and the River Wye looking sleek and animated and glossy, and where, on some roads, you move from England to Wales and back again with dizzying ease and frequency. That was in a foreign country. . .

As for birds. . . . In a few days and in a limited area, we saw or heard (frequently both), skylark, chaffinch, blackbird, robin, blackcap, sparrow, wood pigeon, linnet, chiffchaff, wren, dunnock, crow, goldfinch and song thrush (Buchan’s ‘mavis’).[3] Many of these in the trees and the grass outside the living-room or kitchen windows of the farmhouse we were renting, others on walks through fields and woods.

Birds we had, then, in abundance. Space and grass and sheep and silence also. Wi-Fi, broadband, not so much. ‘I’ve rebooted it and logged on several times, it seems fine now’, the housekeeper said before leaving. The blue light lasted for at least a minute. The Librarian tried resetting it a few times, quite a few times, over the next few days with the same result. But we had food, wine, books and packs of cards. There were mobile phones too, in the event of an emergency. We survived. And what lengths would we go to, should we go to, for the latest news? After all, given the current state of things, should you not warm to neo-fascist extremism or the aggressive erasure of history or the continuing mass murder of civilians or the vicious suppression of non-violent protest, there’s little in daily bulletins to lift the spirits. Some people, though—and I have it on the best authority—can find it oddly cheering to see, as they cross a field from stile to stile, a pheasant strolling to and fro in that field, apparently without a care in the world.

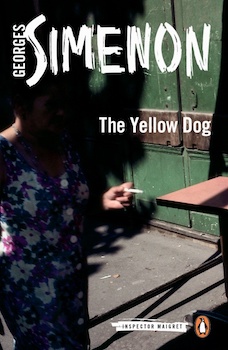

So Inspector Jules Maigret sweltered in August heat or remained on edge when ‘no one had ever known such a damp, cold gloomy March.’[4] Virginia Woolf did not go to the party at Gordon Square where the d’Aranyi sisters, Adila, Hortense and Jelly (‘great-nieces of the renowned Hungarian violinist Joachim’) would be playing, because Leonard arrived home too late, ‘& it rained, & really, we didn’t want to go.’[5] And I was glad to learn about the Society of Dilettanti, concerned with practical patronage of the arts, whose members included Sir Joshua Reynolds, David Garrick and Charles James Fox, and to be told of Horace Walpole’s writing that, while the nominal qualification for membership of the Society was having been to Italy, the real one was being drunk.[6]

After the diversions of fictional Paris and historical Brighton, I am now with James Boswell, young Boswell on his Grand Tour, after Holland, currently in Germany, soon to be in Switzerland. He is still often preposterous, still wholly irresistible—and still battling with the Black Dog (‘The fiend laid hold of me’). But he finds diversions enough: ‘I must not forget to mark that I fell in love with the beauteous Princess Elizabeth. I talked of carrying her off from the Prince of Prussia, and so occasioning a second Trojan War.’[7]

We are back, then, via taxi and train among Good Friday crowds, walking again in the park amidst hurtling spaniels rather than quietly to and fro along a secluded lane with teeming hedgerows, remarkable trees and glimpses of an unfamiliar breed of sheep, which gave rise to a good deal of highly technical agricultural vocabulary: ‘God, they’re chunky!’ Too far away for a convincing photograph but, scanning various sheep breeders’ websites, we agree that they were probably Zwartbles.

As confirmed by such remarks, we are now returned to what E. M. Forster termed the world of ‘telegrams and anger’—minus the telegrams, of course, and seemingly with many times the anger. We are also back, that is to say, in the firm grip of the internet. Does that warrant one cheer or two?

Notes

[1] James Boswell, The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides with Samuel Johnson, LL.D., edited by Ian McGowan (1785; Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 1996), 234-235.

[2] John Buchan, ‘April in the Hills’, in Scholar-Gipsies (1896; London: John Lane The Bodley Head, 1927), 28.

[3] Apparently derived from the French mauvis (though, confusingly, this seems to mean ‘redwing’, turdus iliacus rather than turdus philomelos). ‘It is still used for the bird in Orkney and survives elsewhere in Scotland’: Mark Cocker and Richard Mabey, Birds Britannica (London: Chatto & Windus, 2005), 358-359.

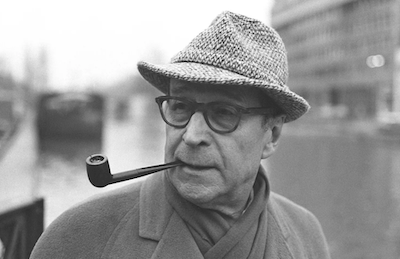

[4] Georges Simenon, Maigret’s Failure, translated by William Hobson (Penguin Books, 2025), 1; August heat in Maigret Sets a Trap, translated by Siân Reynolds (London: Penguin Books, 2017).

[5] The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Volume 1: 1915-19, edited by Anne Olivier Bell (with the Asheham Diary, London: Granta, 2023), 11-12.

[6] Venetia Murray, High Society in the Regency Period: 1780-1830 (London: Penguin Books, 1999), 165.

[7] Boswell on the Grand Tour: Germany and Switzerland 1764, edited by Frederick A. Pottle (London: William Heinemann, 1953), 12, 67.