(Ford Madox Ford and Violet Hunt at Selsey)

On 9 February 1911, The New Age published a letter to the editor from Giessen, in Germany, outlining the writer’s reasons for supporting women’s suffrage:

‘As for the question of militant tactics, I am certainly in favour of them. It is the business of these women to call attention to their wrongs, not to emphasise the fact that they are pure as the skies, candid as the cliffs of chalk, unsullied as the streams, or virginal as spring daffodils. They are, of course, all that—but only in novels. This is politics, and politics is a dirty business. They have to call attention to their wrongs, and they will not do that by being “womanly.” Why should we ask them to be? We cannot ourselves make omelettes without breaking eggs. Why should we ask them to?’[1]

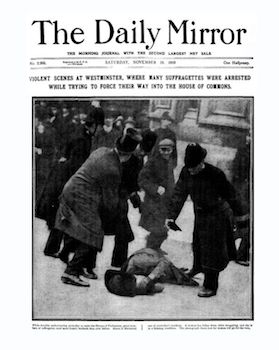

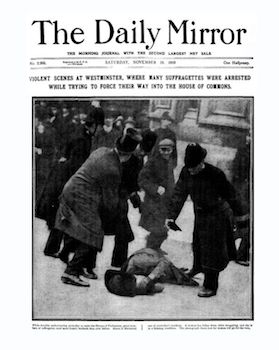

Ford Madox Ford was in Giessen, enmeshed in the maze of the country’s civil law, as part of a ludicrous scheme to secure German citizenship and thus obtain a divorce from his wife Elsie, so that he might marry the novelist (and suffragette) Violet Hunt. His letter came just three months after ‘Black Friday’, 18 November 1910, when the police had physically – and, in some cases, sexually – assaulted the women demonstrators marching on Parliament.

In his Ancient Lights, which appeared the following month, Ford would assert that, ‘Personally I am an ardent, an enraged suffragette.’[2] He was certainly a productive one. The previous year, he had published, in an English Review editorial, several pages on ‘Women’s Suffrage’, primarily an attack on the Liberal government’s pig-headedness, in particular the devious methods and bad faith shown by Asquith, and the press’s refusal to publish details of abuses together with its readiness to publish more sensational accounts based on dubious sources.[3]

‘In one of His Majesty’s gaols, the doctor officiating at the forcible feeding of one of the women caught her by the hair of the head and held her down upon a bed whilst he inserted—in between her teeth that, avowedly, he might cause her more pain—the gag that should hold her mouth open, and there was forced down her throat one quart of a mixture of raw oatmeal and water. In the barbarous and never to be sufficiently reprehended Middle Ages this punishment was known as the peine forte et dure.’

Ford granted the urgency of some of the major legislation that Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George wished to push through but pointed out, ‘that very urgency makes the necessities of the women by ten times the more urgent. For the reforms that Mr. Lloyd George and his friends desire are precisely social reforms and social reforms precisely concern women even more than men.’ There had been proposals to abolish the House of Lords’ legislative veto: ‘this may be for the good of the people or it may prove the people’s bane. But there can be no doubting that in making these demands Mr. Lloyd George and his friends are asking to be allowed to become the autocratic rulers of the immense body of voiceless and voteless women. As far as the men of the country are concerned the Cabinet will be at least nominally popularly elected. For women they will be mere tyrants.’[4]

Later that year, in four issues of The Vote, Ford published ‘The Woman of the Novelists’, in the form of ‘an open letter’, which became the seventh chapter of his The Critical Attitude (1911).[5] He remarked that, much of the time, when men talked about women, they were, in fact, talking about ‘the Woman of the Novelist!’[6] As readers and consumers of books, women could exert a significant influence over the ways in which male authors portrayed them; but, Ford suggested, ‘it should be a self-evident proposition that it would be much better for you to be, as a sex, reviled in books. Then men coming to you in real life would find how delightful you actually are, how logical, how sensible, how unemotional, how capable of conducting the affairs of the world. For we are quite sure that you are, at least we are quite sure that you are as capable of conducting them as are men in the bulk. That is all we can conscientiously say and all, we feel confident, that you will demand of us.’[7]

Six years after the Representation of the People Act, in the first part of Some Do Not. . ., which can be confidently dated to 1912, Ford has the Tory younger son of a Yorkshire landowning family discuss matters in general, and the Pimlico army clothing factory case in particular, with the young suffragette, Valentine Wannop:

(Adelaide Clemens as Valentine Wannop in the BBC/HBO/VRT television adaptation of Parade’s End)

‘Now, if the seven hundred women, backed by all the other ill-used, sweated women of the country, had threatened the Under-Secretary, burned the pillar-boxes, and cut up all the golf greens round his country-house, they’d have had their wages raised to half-a-crown next week. That’s the only straight method. It’s the feudal system at work.’

‘Oh, but we couldn’t cut up golf greens,’ Miss Wannop said. ‘At least the W.S.P.U. debated it the other day, and decided that anything so unsporting would make us too unpopular. I was for it personally.’

Tietjens groaned:

‘It’s maddening,’ he said, ‘to find women, as soon as they get in Council, as muddleheaded and as afraid to face straight issues as men! . . .‘[8]

Certainly by the following year, golf greens, along with tennis courts, bowling greens and racecourses, were among the casualties as Suffragette protest increased in militancy. It was in 1913 that the Women’s Freedom League published Ford’s pamphlet entitled This Monstrous Regiment of Women.[9] His title derives from the fervid Protestant John Knox, whose First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women appeared in 1558, damning rule by women as unnatural and repugnant. It was directed primarily against the Catholic Mary Tudor (as well as the Scots queen Mary Stuart and her mother) but, with monstrously bad timing, appeared just months before the accession to the English throne of Elizabeth – who was not amused.

(Mary Tudor)

Ford begins his pamphlet, in fact, with the great gains made for England in wealth and power during Elizabeth’s reign, following it with the rejuvenation of the institution of the British throne under Victoria, though he warns against running the theory too hard, given that another queen in that period was Mary, ‘who is generally known as “bloody”’, and also Anne, ‘who is principally known because she is dead’, though her reign, at least at home, ‘was one of comparative peace’. He concludes that, appealing to the reader’s common sense, rather than ‘to prove romantic notions’, he has merely set out to prove, and has surely proved, ‘that in England it has been profitable to have women occupying the highest place of the State.’

One of Ford’s critics remarks, sharply but perhaps not entirely unjustifiably, that Ford ‘took pleasure in feeling more qualified to diagnose the problems with women than women themselves’.[10] It’s certainly arguable that, while his support for women’s suffrage was genuine and sustained, he was often prone to wanting to have his cake and eat it. He was hardly unusual in that: indeed, there have been recent attempts to present such wanting as a coherent political strategy. As Joseph Wiesenfarth remarks, ‘Ford’s personal life suggests that he treated women as equals. He treated them as well and as badly as he treated men’.[11]

Treated – and was treated, at least in Ford’s own view. While at Giessen, he also began writing Women and Men: ‘I have personally been treated badly by men who behaved as if they were wolves. On the other hand I have been badly treated by women who behaved as if they were hyenas.’[12]

On the one hand, wolves; on the other, hyenas. It’s not just the BBC that knows about balance.

References

[1] The New Age, VIII (9 February 1911), 356-357; see Letters of Ford Madox Ford, edited by Richard M. Ludwig (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965), 49.

[2] Ford Madox Ford, Ancient Lights and Certain New Reflections (London: Chapman and Hall, 1911), 294.

[3] Ford Madox Ford, ‘The Critical Attitude’, English Review, IV (January, 1910), 332-338.

[4] Ford, ‘The Critical Attitude’, 333, 336.

[5] ‘The Woman of the Novelists’, The Vote, II (27 August, 3 September, 10 September, 17 September, 1910).

[6] Ford Madox Ford, The Critical Attitude (London: Duckworth, 1911), 151, 152.

[7] Ford, The Critical Attitude, 168-169.

[8] Ford Madox Ford, Some Do Not. . . (1924; edited by Max Saunders, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2010), 145.

[9] The pamphlet is reprinted in Sondra Stang, editor, The Ford Madox Ford Reader (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1986), 304-317.

[10] James Longenbach, ‘The Women and Men of 1914’, in Helen M. Cooper, Adrienne Auslander Munich and Susan Merrill Squier, editors, Arms and the Woman: War, Gender, and Literary Representation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989), 108.

[11] Joseph Wiesenfarth, Ford Madox Ford and the Regiment of Women: Violet Hunt, Jean Rhys, Stella Bowen, Janice Biala (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2005), 27.

[12] Ford Madox Ford, ‘Women and Men—I’, Little Review, IV (January, 1918), 27.