(Frederick James Shields, Hamlet and the Ghost: Manchester Art Gallery)

Saturday’s Guardian carried a paperback review of Lisa Morton’s Ghosts: A Haunted History. It begins: ‘Nearly half of Americans believe in ghosts; the worldwide figure is almost certainly higher’, and adds that Morton shows belief in ghosts to be ‘nearly universal, though the form taken by the “undead spirit” varies across time and space.’[1]

It’s certainly a remarkably prevalent word – and idea – in our culture, in most cultures. Ghostwriter, ghost story, Ghostbuster, ghost train, ghost town, ghost of a chance, give up the ghost, to look like a ghost, ghosts walking over our graves, the ghost in the machine. The Holy Ghost: the Divine Spirit, the third person of the trinity, the Holy Spirit, closer there to the German geist. Ford Madox Ford remembered telling his confessor about his difficulty in conceiving, let along believing in, that ‘Third Person of the Trinity’. The old priest sensibly replied: ‘“Calm yourself, my son, that is a matter for theologians. Believe as much as you can”.’[2]

The poet Thomas Campbell recalled meeting the celebrated astronomer William Herschel in Brighton, in September 1813, feeling that he’d been ‘conversing with a supernatural intelligence’. Herschel completely perplexed him by saying that many distant stars had probably ceased to exist ‘millions of years ago’, ‘and that looking up into the night sky we were seeing a stellar landscape that was not really there at all. The sky was full of ghosts.’[3]

I’d tended to assume that fear of ghosts in the old sense had sensibly diminished in the more than four hundred years since Hamlet and the other witnesses had no doubts at all about what they were seeing when the ghost of the late king appeared to them, or the two hundred and fifty years since James Boswell was so unsettled by talk of ghosts: ‘This was very strong. My mind was now filled with a real horror instead of an imaginary one. I shuddered with apprehension. I was frightened to go home’.[4]

Had interest not steadily shifted to the observer rather than the observed? Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw is an obvious example; and Algernon Blackwood, in the preface to his collected stories, wrote: ‘My interest in psychic matters has always been the interest in questions of extended or expanded consciousness. If a ghost is seen, what is it interests me less than what sees it?’[5]

(Ghosts at the Almeida Theatre via The Telegraph)

Lesley Manville as Helene Alving and Jack Lowden as Oswald Alving.

Henrik Ibsen disliked Ghosts as the title chosen by William Archer for his translation of the play into English. Richard Eyre, discussing his 2013 version, rendered the Norwegian Gengangere as ‘“a thing that walks again”, rather than the appearance of a soul of a dead person’ but pointed out that ‘Againwalkers’ was ungainly and the alternative, ‘Revenants’ he found ‘both awkward and French. Ghosts has a poetic resonance to the English ear.’

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2013/sep/20/richard-eyre-spirit-ibsen-ghosts

Awkward? Arguably. French, most certainly. The 2004 film, Les Revenants, I’ve seen translated as They Came Back, while the recent television series based on it is called The Returned. In any case, the poetic resonance of ‘ghosts’ is certainly true enough in this English ear.

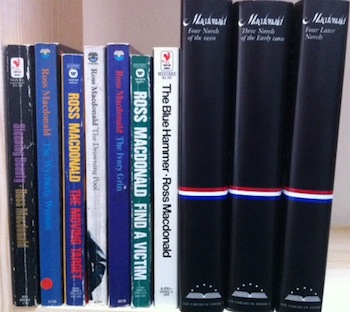

Unsurprisingly, the ‘theatre of war’—‘“theatre” is good. There are those who did not want / it to come to an end’[6]—is a flourishing site of wraiths, phantoms, visitants, revenants and vanishings. ‘Ghosts were numerous in France at that time’, Robert Graves wrote, recalling the second year of the First World War. Later, staying near Harlech at the large Tudor house of the Nicholson family—Graves married Nancy Nicholson, sister of Ben, third child of the painter William Nicholson and his wife Mabel—Graves remembered, ‘It was the most haunted house that I have ever been in, though the ghosts were invisible except in the mirrors.’[7]

(By Source (WP:NFCC#4), Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51483551)

From France in 1916, Ford Madox Ford wrote to Lucy Masterman, wife of the Liberal politician, then running the British War Propaganda Bureau (Wellington House): ‘Why does nobody write to me? Does one so quickly become a ghost, alas!’[8]

And two and a half years after the Armistice, Siegfried Sassoon, thinking about the war, pulled out his war notebooks and paused on a diary entry of 30 June 1916. ‘The diary makes me realise that I shall never partake of another war. It makes me wonder whether five years ago was real. “Gibson’s face in the first grey of dawn . . . ” Gibson is a ghost but he is more real to-night than the pianist who played Scriabine with such delicate adroitness. I wish I could “find a moral equivalent for war”. To-night I feel as if I were only half-alive. Part of me died with all the Gibsons I used to know.’[9]

Rapid and colossal changes, in agriculture, in urban sprawl, in transport, in technology, in population density, in the widespread loss of natural habitats, the accelerating extinction of species, the rampant carelessness of planning and development, combine to engender common but unpredictable sensations of loss, an uneasiness, an unfocused search for the missing. ‘Our landscape is full of ghosts’, Anna Pavord writes, ‘of hands that have twitched and pulled it into sheep runs and cattle folds, bridleways and burial mounds. It is one of its great strengths.’[10] And Helen Macdonald wrote that ‘The hawk and I have a shared history of these fields. There are ghosts here, but they are not long-dead falconers. They are ghosts of things that happened.’[11]

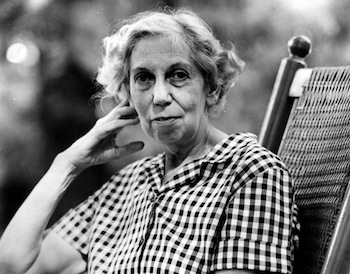

The self, of course, can become a ghost, or feel like one. Writing to William Maxwell in early 1940, Sylvia Townsend Warner remarked: ‘Being a writer makes one a ghost before one’s time—the kind of ghost that likes a libation. War—or rather a state of things that antedates war—makes one feel more ghostly still’.[12] John Banville’s narrator refers to the self as an indistinct black shape, ‘like the shape that no one at the séance sees until the daguerreotype is developed. I think I am becoming my own ghost.’[13]

(Sylvia Townsend Warner via http://sylviatownsendwarner.tumblr.com/)

How many of us are never haunted, by remembered faces, voices, names, the lives unlived, places unvisited, old friends misplaced, acquaintances not pursued, desired lovers untried? We may not use the word ‘ghost’, of course. But sometimes one of the most poignant experiences of the ghostly is not the dead friend or relative or lover, the spirit reluctant to leave building, battlefield or landscape—but the life that was never quite there at the outset, the lost because never held, the almost-life, as in the poem by Julia Copus, her narrator straining to see the longed-for sign of a successful IVF treatment:

She takes it all in, like a small, controlled explosion:

here is the inch-long stiff, absorbent pad –

a stopped tongue, the damp on it still; and the plastic housing

with its cut-out windows. And here is the latex strip

(two lines for yes), the single band of purple

and beside it the silvery ghost of a second line

willed into being – frail as the arm of a sea-frond

trailed in the ocean – but failing to darken or turn

into more than a watermark.[14]

References

[1] P. D. Smith, ‘Out in paperback’ column, which I cannot find online: Guardian review supplement (7 October 2017), 9.

[2] Ford Madox Ford, Provence (London: Allen & Unwin, 1938), 140.

[3] Richard Holmes, The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science (London: Harper Collins, 2008), 210.

[4] Boswell’s London Journal, 1762-1763, edited by Frederick A. Pottle (London: William Heinemann, 1950), 214.

[5] The Tales of Algernon Blackwood (London: Martin Secker, 1938), xi.

[6] ‘Canto LXXVIII’, The Cantos of Ezra Pound, fourth collected edition (London: Faber and Faber, 1987), 477.

[7] Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That (1929 edition; Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2014), 157, 342; Sanford Schwartz, William Nicholson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 179-180.

[8] Letter of 6 September 1916: Letters of Ford Madox Ford, edited by Richard M. Ludwig (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965), 74.

[9] Siegfried Sassoon, Diaries 1920-1922, edited by Rupert Hart-Davis (London: Faber and Faber, 1981), 73.

[10] Anna Pavord, Landskipping: Painters, Ploughmen and Places (London: Bloomsbury 2016), 43.

[11] Helen Macdonald, H is for Hawk (London: Jonathan Cape, 2014), 240.

[12] Michael Steinman, editor, The Element of Lavishness: Letters of Sylvia Townsend Warner and William Maxwell, 1938-1978 (Washington: Counterpoint, 2001), 8.

[13] John Banville, The Sea (London: Picador, 2006), 194.

[14] Julia Copus, ‘Ghost’, in The World’s Two Smallest Humans (London: Faber and Faber, 2012), 50.