There are seven, or is it eight, buds on our rosebush now. Like many readers, I can call to mind the first line of Robert Herrick’s ‘Gather ye rosebuds while ye may’ but then I tend to falter. The poem’s usual title, ‘To the Virgins, to make much of time’, points to those preoccupations with sex and death which are so common in the poetry of that period, perfectly reasonably so, given wars, plagues and an average life expectancy of less than forty years (that this was heavily influenced by a very high infant mortality rate can’t have been that much comfort). So the other three lines of Herrick’s first stanza are:

Old Time is still a-flying:

And this same flower that smiles to-day

Tomorrow will be dying.[1]

Be not coy, he advises those maidens, an admonition moved up to headline status in Andrew Marvell’s wonderful To His Coy Mistress. Marvell is also extremely keen to get his lover into bed: of course, he’d like nothing better than to devote tens, hundreds, even thousands of years to praising and adoring her eyes, forehead, breasts and heart. ‘But’, alas, ‘at my back I always hear/ Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near’. And he points out, quite sensibly, that ‘The grave’s a fine and private place,/ But none, I think, do there embrace.’[2]

So the rose, or rather, the beauty of the rose, is inextricable from the brevity of its flowering. There are, I see now, a staggering number of poems about roses and often, simultaneously, about beauty, sex and death also. They stretch back to the ancient world—Homer, Horace, Sappho—up through Shakespeare and Milton to the modern period of Frost, H. D., Yeats, De la Mare, Randall Jarrell and Charles Tomlinson.

Go, lovely Rose—

Tell her that wastes her time and me,

That now she knows,

When I resemble her to thee,

How sweet and fair she seems to be.[3]

(Edmund Waller, after John Riley)

This is the first stanza of the famous lyric by Edmund Waller (1606-1687), poet and politician; involved in a 1643 plot in the interest of the king, he escaped execution and was banished to France, returning to England in 1652 and becoming an admirer and friend of Oliver Cromwell.

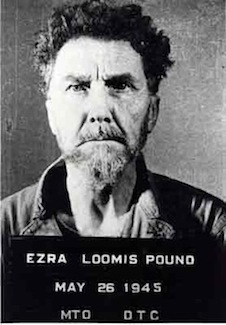

And here’s the first stanza of the ‘Envoi’, carefully dated (1919), to the first part of Ezra Pound’s Hugh Selwyn Mauberley:

Go, dumb-born book,

Tell her that sang me once that song of Lawes:

Hadst thou but song

As thou hast subjects known,

Then were there cause in thee that should condone

Even my faults that heavy upon me lie

And build her glories their longevity.

The speaker then thinks of how the grace and beauty might be made to outlast its moment, its natural lifespan, as roses might be made to do:

Tells her that sheds

Such treasure in the air,

Recking naught else but that her graces give

Life to the moment,

I would bid them live

As roses might, in magic amber laid,

Red overwrought with orange and all made

One substance and one colour

Braving time.[4]

Henry Lawes set Waller’s ‘Goe lovely Rose’ to music; ‘her that sang me once that song of Lawes’ was almost certainly Raymonde Collignon (Madame Gaspard-Michel), who made her professional debut in 1916, was favourably reviewed several times by Pound when he reviewed music for the New Age under the name ‘William Atheling’, and performed in Pound’s opera, The Testament of François Villon.[5]

A quarter of a century later, in the last pages—what I think of as the ‘English’ pages—of Canto LXXX, part of the Pisan sequence, Pound wrote:

Tudor indeed is gone and every rose,

Blood-red, blanch-white that in the sunset glows

Cries: ‘Blood, Blood, Blood!’ against the gothic stone

Of England, as the Howard or Boleyn knows.[6]

(© National Portrait Gallery, London

Unknown woman, formerly known as Catherine Howard

after Hans Holbein the Younger; oil on panel, late 17th century)

The red rose of Lancaster and the white rose of Yorkshire: the thirty-year-long Wars of the Roses and the passing of the Plantagenet dynasty; then the deaths of Katharine Howard and Anne Boleyn on the block; followed by the end of the Tudors with the death of Elizabeth.

But Pound used roses in another context: their delicacy, fragility and vulnerability set against the patterning of energy made visible by, for instance, iron filings acted upon by a magnet.

Hast ‘ou seen the rose in the steel dust

(or swansdown ever?)

so light is the urging, so ordered the dark petals of iron

we who have passed over Lethe.[7]

Pound first mentioned his magnetic ‘rose’ in a 1915 piece on Vorticism, at a time when he was preoccupied with forms of energy. ‘An organisation of forms expresses a confluence of forces [ . . . . ] For example: if you clasp a strong magnet beneath a plateful of iron filings, the energies of the magnet will proceed to organise form. It is only by applying a particular and suitable force that you can bring order and vitality and thence beauty into a plate of iron filings, which are otherwise as “ugly” as anything under heaven. The design in the magnetized iron filings expresses a confluence of energy.’[8]

He returned to the theme—and the image—again in an essay on the medieval Italian poet Guido Cavalcanti,[9] and in 1937, once again found the rose revivified by magnetic energy: ‘The forma, the immortal concetto, the concept, the dynamic form which is like the rose pattern driven into the dead iron-filings by the magnet, not by material contact with the magnet itself, but separate from the magnet. Cut off by the layer of glass, the dust and filings rise and spring into order. Thus the forma, the concept rises from death’.[10]

The idea and the image tend to divert attention from the language used: but the words themselves form highly effective, opposing clusters: ‘dead’ and ‘death’, ‘separate’ and ‘cut off’ set against ‘immortal’, ‘dynamic’, ‘rise’, ‘spring’, ‘rises’.

Eighty years earlier, another writer—another highly contentious figure—began his own rose-centred obsession. John Ruskin, in the preface to his autobiography, Praeterita, referred to ‘passing in total silence things which I have no pleasure in reviewing, and which the reader would find no help in account of.’ Later in the same book, he writes that ‘Some wise, and prettily mannered, people have told me I shouldn’t say anything about Rosie at all. But I am too old now to take advice…’[11]

Rosie—Rose La Touche—was ten years old when she first met Ruskin. She died at the age of twenty-seven. He seems to have asked her to marry him around her eighteenth birthday, though he had clearly fallen in love with her some time before that: she asked him to wait for an answer until she was twenty-one. The story of this long, sad affair, complicated by parental concern, religious mania and Ruskin’s well-documented predilection for young girls, has been traced at length by Ruskin’s biographers. Tim Hilton states baldly that Ruskin ‘was a paedophile’,[12] which, certainly in today’s cultural climate, seems to say both too much and too little. As Catherine Robson points out, ‘There is no evidence that Ruskin sexually abused little girls: the exact dynamics of his encounters with real girls—with Rose La Touche, with the pupils at Winnington, with girls in London, France, Italy, Switzerland, the Lake District—remain essentially unknowable.’[13] Given the ‘non-consummation’ of Ruskin’s marriage with Effie Gray, it seems highly likely that Ruskin never had a full sexual relationship at all.

Roses are everywhere in Ruskin’s work, from the title of his botanical book, Proserpina—not only does the title embrace the word ‘rose’ but Ruskin associated Rose La Touche with Proserpina since at least the spring of 1866[14]—to numerous pages in Fors Clavigera, not least the ‘little vignette stamp of roses’ on the title page, of which he writes in ‘Letter XXII’: ‘It is copied from the clearest bit of the pattern of the petticoat of Spring, where it is drawn tight over her thigh, in Sandro Botticelli’s picture of her, at Florence.’[15]

(Rose La Touche by John Ruskin, 1861)

And at the last, in ‘Letter XCVI. (Terminal)’ of his great work, Ruskin talks of ‘a place called the Rosy Valley’, which becomes ‘Rosy Vale’, the title of the letter. Rosy Vale, ‘Rosy farewell’. At the head of the letter is a drawing by Kate Greenaway, called, of course, ‘Rosy Vale’. And Fors Clavigera closes with these words: ‘The story of Rosy Vale is not ended;—surely out of its silence the mountains and the hills shall break forth into singing, and round it the desert rejoice, and blossom as the rose.’[16]

How much this painful history contributed to Ruskin’s depression and mental decline is impossible to gauge. Rose had died mad in 1875; from 1889 to his death in 1900, Ruskin produced little and, apparently, spoke little, that span of a dozen years eerily echoed in the life of Friedrich Nietzsche, who suffered a mental collapse in 1889 but lived on until 1900. For the last dozen years of his life, Ezra Pound produced practically nothing and spoke—in public—barely at all.

‘You think I jest, still, do you? Anything but that; only if I took off the Harlequin’s mask for a moment, you would say I was simply mad. Be it so, however, for this time.’[17]

References

[1] The Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1918, edited by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966), 274.

[2] Andrew Marvell, ‘To His Coy Mistress’, in The Complete Poems, edited by Elizabeth Story Donno (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1986), 50. Some readers of Ford Madox Ford prick up their ears at this point, remembering General Campion’s quoting (and misquoting) of this poem: No More Parades (1925; edited by Joseph Wiesenfarth, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2011), 219-220.

[3] The Oxford Book of English Verse, 318.

[4] Ezra Pound: Poems and Translations, edited by Richard Sieburth (New York: Library of America, 2003), 557.

[5] Eva Hesse, ‘Raymonde Collignon, or (Apropos Paideuma, 7-1 & 2, 345-346): The Duck That Got Away’, Paideuma, 10, 3 Winter 1981), 583-584.

[6] The Cantos of Ezra Pound, fourth collected edition (London: Faber and Faber, 1987), 516.

[7] ‘Canto LXXIV’, The Cantos of Ezra Pound, 449. Pound critics point to Ben Jonson’s ‘Her Triumph’ here; and to the form of Edward Fitzgerald’s The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám in the case of the previous quotation.

[8] Ezra Pound, ‘Affirmations II. Vorticism’, New Age, XVI, 11 (14 January, 1915), 277. Later in the series, an article on Imagism mentioned ‘energy’ or ‘energies’ twelve times, ‘emotion’ or ‘emotional’ sixteen times.

[9] Literary Essays of Ezra Pound, edited by T. S. Eliot (London: Faber and Faber, 1960), 154.

[10] Pound, Guide to Kulchur (1938; New Directions, 1970), 152,

[11] Ruskin, Praeterita and Dilecta (London: Everyman’s Library, 2005), 9, 471.

[12] Tim Hilton, John Ruskin: The Early Years (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1985), 253.

[13] Catherine Robson, Men in Wonderland: The Lost Girlhood of the Victorian Gentleman (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001), 122.

[14] Tim Hilton, Ruskin: The Later Years (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000), 311.

[15] Ruskin, Fors Clavigera: Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain, new edition (Orpington & London: George Allen, 1896), I, 427.

[16] Ruskin, Fors Clavigera, IV, 507.

[17] Ruskin, Fors Clavigera, III, 257,