(Norman Garstin, The Rain It Raineth Every Day: Penlee House Gallery & Museum)

January, so far, has consisted—almost exclusively—of rain. Oh, food and drink, books and conversation—and the rabbit-holing so familiar to researchers, following threads that snap or falter or turn out not to be threads at all. But, primarily, persistent, consistent, insistent rain – with a constant soundtrack of sirens, occasionally police, once or twice fire but mainly, almost always, ambulance. Talking, sounding, wailing, rabbiting on. Which, me being so literary these days, recalls The Good Soldier:

Leonora was standing in the window twirling the wooden acorn at the end of the window-blind cord desultorily round and round. She looked across the lawn and said, as far as I can remember:

“Edward has been dead only ten days and yet there are rabbits on the lawn.”’

I always liked ‘as far as I can remember’, so neatly placed in a novel constructed by memories, or what purport to be memories (a few lines later, Dowell will ‘remember her exact words’ about Florence and suicide). As for those Fordian rabbits, I’ve already had my say.[1]

It is, after all, as my friend Helen reminded me, the Year of the Rabbit, according to the Chinese Zodiac (the last one was 2011). At least, on 22 January, it’s farewell to Tiger and hello again to Rabbit. In a brilliant blue sky a week ago (such details tend to be firmly set in such a rain-sodden mental map), quite insubstantial clouds were drifting. Inevitably I drifted too, in the general direction of literary rabbits who were neither Joel Chandler Harris’s Brer Rabbit nor John Updike’s Rabbit Angstrom. Of Updike’s quartet, I read the first two, decades ago, but never circled round to the others. Harris’s ‘Brer Rabbit and the Tar Baby’, one of the African-American trickster tales that he popularised, was, I think, the story that I was reading part of to an American literature seminar group but laughed too much to continue.

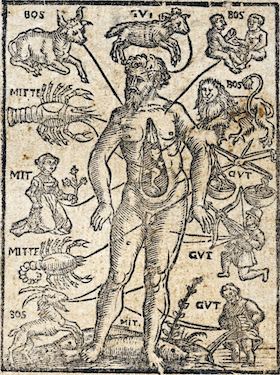

Frobenius and Fox wrote, in their introduction to African Genesis (1937) that: ‘The Berber tales are folklore; and in the Berber jackal we meet that shrewd, amusing and unscrupulous spirit always present in peasant lore, whether it be the jackal here, the hare in South Africa (a veritable Brer Rabbit) or the cunning little fox in the Baltic countries (Reinecke Fuchs).’[2] And Guy Davenport observes that: ‘The Dogon, a people of West Africa, will tell you that a white fox named Ogo frequently weaves himself a hat of string beans, puts it on his impudent head, and dances in the okra to insult and infuriate God Almighty, and that there’s nothing we can do about it except abide him in faith and patience.

‘This is not folklore, or a quaint custom, but as serious a matter to the Dogon as a filling station to us Americans. The imagination; that is, the way we shape and use the world, indeed the way we see the world, has geographical boundaries like islands, continents, and countries. These boundaries can be crossed. That Dogon fox and his impudent dance came to live with us, but in a different body, and to serve a different mode of the imagination. We call him Brer Rabbit.’[3]

Rabbits run through many children’s minds (and those of their parents, pretty often): Charlotte Zolotow’s Mr Rabbit and the Lovely Present, Margery Williams’ The Velveteen Rabbit, Sam McBratney’s Guess How Much I Love You, Rosemary Wells’ Morris’s Disappearing Bag, Alison Uttley’s Little Grey Rabbit, Lewis Carroll, A. A. Milne, Richard Adams. In 1890, a collection of doggerel by Frederic E. Weatherley, A Happy Pair, included illustrations by Beatrix Potter, the last of which accompanied a verse called ‘Benjamin Bunny’. At the family home in Bolton Gardens, Beatrix’s pet rabbits were indeed named Peter Rabbit and Benjamin Bunny. Weatherley was then a barrister but later became a prolific songwriter, turning out something like 3000 popular songs, most notably Roses of Picardy.[4]

The poet Edmund Blunden, author of the First World War classic, Undertones of War, was nicknamed ‘Rabbit’, at least by his Colonel Harrison, though Blunden himself seemed concerned on occasion to upgrade this, recalling a moment when, together with a fellow soldier, ‘we ran (myself asthmatical, but swifter than a hare)’.[5] David Garnett was known to friends and family as ‘Bunny’, though he too slipped the snare of his nickname—if in the reverse direction—when reaching for the title of his 1932 account of learning to fly: A Rabbit in the Air.[6] The Garnett family had other dealings with rabbits. David’s aunt Olive noted in her diary for 5 May 1892 that at her brother Edward’s cottage, where he lived with his wife Constance, famous translator of Russian literature: ‘The wild creatures are becoming bold, the rabbits are actually burrowing under the parlour window & are expected to come up through the floor.’[7]

D. H. Lawrence was familiar with every aspect of the natural world – and the first sketch I ever read of his was, I think, ‘Adolf’, about the ‘tiny brown rabbit’ his father brings home one morning after his work on the nightshift. Another short piece, ‘Lessford’s Rabbits’—no pun intended?—was written soon after Lawrence met Ford, then editing the English Review.[8] Ursula Brangwen’s selection of ‘The Rabbit’ as a theme for her class’s composition goes down badly with headmaster Harby: ‘“A very easy subject for Standard Five”’—at which Ursula feels ‘a slight shame of incompetence. She was exposed before the class.’[9]

The Rainbow was, notoriously, prosecuted and all copies and sheets ordered to be destroyed, his publisher Methuen having rolled over in time-honoured fashion and apologised in all directions.[10] Douglas Goldring, who had met Lawrence when working with Ford on the English Review, also had small burrowing animals on his mind when he wrote: ‘Then what a change of front! The deafening silence, broken only by the sound of the white rabbits of criticism scuttling for cover, which formed the sequel to The Rainbow prosecution, will not soon be forgotten by those who were in London at the time. Not one of Mr. Lawrence’s fervent boosters ventured into print to defend him; not one of his brother authors (save only Mr. Arnold Bennett, to whom all honour is due) took up the cudgels on his behalf. English novelists are proverbially lacking in esprit de corps, but surely they were never so badly shown up as when they tolerated this persecution of a distinguished confrère without making a collective protest.’[11]

(Holliday Grainger as Connie Chatterley via BBC)

A dozen years later, writing the second version of his final novel, Lawrence had Parkin (later Mellors) write to Connie Chatterley: ‘“I shouldn’t care if the bolshevists blew up one half of the world, and the capitalists blew up the other half, to spite them, so long as they left me and you a rabbit-hole apiece to creep in, and meet underground like the rabbits do.—”’[12]

There’s always a risk, of course, that references and allusions like this will breed like—I don’t know what. End then with a touch of Rex Stout, who has Costanza Berin put to Archie Goodwin (Nero Wolfe’s indispensable assistant), the question: “Do you like Englishmen?”

‘I lifted a brow. “Well . . . I suppose I could like an Englishman, if the circumstances were exactly right. For instance, if it was on a desert island, and I had had nothing to eat for three days and he had just caught a rabbit—or, in case there were no rabbits, a wild boar or a walrus”’.[13]

‘If the circumstances were exactly right’. Well, yes, I think I’m gravitating to that position myself. But, of course, it’s still very early in the year. . . .

Notes

[1] Ford Madox Ford, The Good Soldier: A Tale of Passion (1915; edited by Max Saunders, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 86; Paul Skinner, “Rabbiting On”: Fertility, Reformers and The Good Soldier’, in Max Saunders and Sara Haslam, editors, Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier: Centenary Essays (Amsterdam: Brill/Rodopi, 2015), 183-195.

[2] Leo Frobenius and Douglas C. Fox, African Genesis (1937; New York: Dover, 1999), 1.

[3] Guy Davenport, The Geography of the Imagination (Boston: David R. Godine, 1997), 3-4.

[4] Margaret Lane, The Tale of Beatrix Potter (1946; Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1962), 50-52.

[5] Edmund Blunden’s Undertones of War (1928; edited by John Greening, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 79, and half a dozen other mentions, though the poem ‘Escape’ (207) has him there as ‘Bunny’, the speaker being ‘A Colonel’. The hare runs on p. 129.

[6] William Maxwell’s young character Peter Morison, in the 1937 novel They Came Like Swallows, was also called ‘Bunny’. In the book, he’s eight years old; Maxwell himself was ten at the time in which the story is set (1918). Then, too, Edmund Wilson—a little less plausibly, somehow—also answered to that name.

[7] Barry C. Johnson, editor, Tea and Anarchy! The Bloomsbury Diary of Olive Garnett, 1890-1893 (London: Bartletts Press, 1989), 73.

[8] ‘Adolf’ is reprinted in Phoenix: The Posthumous Papers of D. H. Lawrence, edited and with an introduction by Edward D. McDonald (London: William Heinemann, 1936), 7-13; ‘Lessford’s Rabbits’ in Phoenix II: Uncollected, Unpublished and Other Prose Works by D. H. Lawrence, Collected and Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Warren Roberts and Harry T. Moore (London: William Heinemann, 1968), 18-23.

[9] D. H. Lawrence, The Rainbow, edited Mark Kinkead-Weekes, introduction and notes Anne Fernihough (Cambridge, 1989; Penguin edition with new editorial matter, 1995), 359-360: the chapter titled ‘The Man’s World’.

[10] Mark Kinkead-Weekes, D. H. Lawrence: Triumph to Exile, 1912-1922 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 281-282.

[11] Douglas Goldring, ‘The Later Work of D. H. Lawrence’, Reputations: Essays in Criticism (London: Chapman & Hall, 1920), 70-71.

[12] The First and Second Lady Chatterley Novels, edited by Dieter Mehl and Christa Jansohn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 564.

[13] Rex Stout, Too Many Cooks, in Too Many Cooks/ Champagne for One (New York: Bantam Dell, 2009), 17.