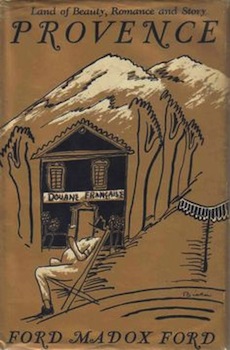

In a recent issue of Last Post, writing of Ford Madox Ford in 1924, Max Saunders remarked that it ‘certainly is an annus mirabilis for Ford; a year in which he launched the transatlantic review, and published two masterpieces: Some Do Not . . ., the first novel of his postwar Parade’s End tetralogy; and the brilliant critical memoir of his collaborator Joseph Conrad’.[1] He was pointing out the objections to the often feverish concentration upon that now-conventional annus mirabilis of modernism, 1922, in literary criticism and history, which has sometimes narrowed down to two particular gleamings in the gloaming, Ulysses and The Waste Land. It’s true that there were dozens of other remarkable works published in that year; lists can easily be constructed and I’ve been guilty of at least one myself. Tempted to do the same thing for 1924, I sailed past a couple of dozen before accepting that 1924 was also guilty of producing an absurd number of interesting items, in addition to the previously mentioned Fordian masterworks.

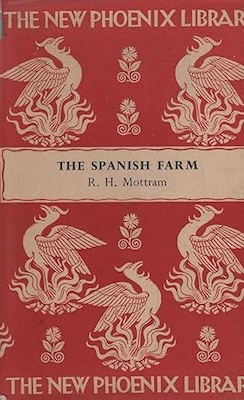

I leave aside, for the moment, Aldous Huxley, Katherine Mansfield, W. B. Yeats, a posthumous Herman Melville, T. E. Hulme, Ernest Hemingway, Glenway Wescott, Marianne Moore and the bestselling The Green Hat by Michael Arlen (formerly Dikrān Kuyumjian) to mention, among my personal favourites, R. H. Mottram’s The Spanish Farm, first volume of a trilogy (the second and third followed in successive years) and winner of that year’s Hawthornden Prize. It focuses primarily not on trench warfare but rather on the narrator’s dealings with the local inhabitants, their claims for loss and damage against the British forces, and the relationship between an English officer and the daughter of the Ferme d’Espagnole. The trilogy was deservedly successful—and published in an omnibus volume in 1927—but has since seemed to drift out of view, only scholars of the period paying much attention to it lately. The one-volume edition was published as a Penguin Modern Classic in 1979 but is long out of print and the only editions currently on offer all look pretty nasty. Mottram was closely identified with Norfolk and sometimes nudged by the familiar British ‘regional novelist’ elbow into some cultural annexe or other. But see Craig Gibson’s piece here: https://norfolkrecordofficeblog.org/2021/04/14/forgotten-r-h-mottram/

Also in this year: John Buchan’s The Three Hostages (Dr Greenslade to Richard Hannay: ‘“Have you ever realized, Dick, the amount of stark craziness that the War has left in the world? . . . I hardly meet a soul who hasn’t got some slight kink in his brain as a consequence of the last seven years”’). There was D. H. Lawrence’s long ‘Introduction’ to Memoirs of the Foreign Legion by Maurice Magnus; Rudyard Kipling wrote four fascinating stories, ‘The Wish House’, ‘The Eye of Allah’, ‘The Bull That Thought’ and ‘A Madonna of the Trenches’ (especially the first two), and Stanley Spencer began The Resurrection in Cookham Churchyard in February 1924 (finished in 1926, it was shown at his first one-man exhibition in 1927).

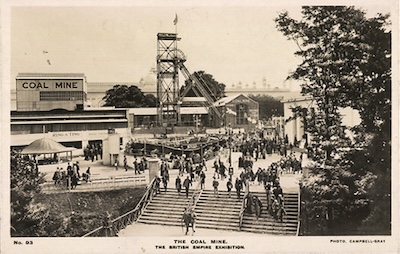

In April, before a crowd of 120,000 people, George V opened the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley, put together by 18,000 workmen: Palace of Art (and Palace of Beauty), Never Stop Railway, Queen’s Doll’s House, butter sculptures, elephants, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, massed choirs in white surplices. Poet and publisher Harold Monro was, apparently, impressed by its patriotic glitter and ‘in one of his satiric dream poems he envisaged an exhibition of the future, where the last Georgian Nature Poet would be on show, dressed in tweed and sipping beer, in a specially designed case.’[2]

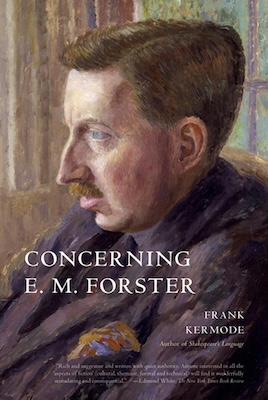

The narrator of Edith Wharton’s ‘The Spark’ comments that ‘People, I had by this time found, all stopped living at one time or another, however many years longer they continued to be alive’.[3] D. H. Lawrence announced to Middleton Murry that he wanted ‘to go south, where there is no autumn, where the cold doesn’t crouch over one like a snow-leopard, waiting to pounce. The heart of the North is dead’.[4] Ezra Pound, well-embarked upon The Cantos by now, was looking back as well as forward, writing in a letter of 3 December to Wyndham Lewis: ‘We were hefty guys in them days; an of what has come after us, we seem to have survived without a great mass of successors’.[5] E. M. Forster published A Passage to India: his next novel, Maurice, would appear 47 years later, following its author’s death. In February 1924, acknowledging Forster’s Pharos and Pharillon, Lawrence wrote to him: ‘To me you are the last Englishman. And I am the one after that.’[6]

In the journal that he kept for a short period, the poet John Clare wrote (30 November 1824): ‘Read the Literary Souvenir for 1825 in all its gilt & finery what a number of candidates for fame are smiling on its pages – what a pity it is that time should be such a destroyer of our hopes & anxiety for the best of us but doubts on fame’s promises & a century will thin the myriad worse than a plague.’[7]

One hundred years on from 1924, the authors and titles of that period present a dazzling image of astonishing abilities and achievements. As to whether, another century on (assuming the continued existence of books, readers or, indeed, people), any of the current ‘candidates for fame’ will be visible to (some version of) literary historians, I have no settled opinion. Let me get back to you.

Notes

[1] Max Saunders, ‘Ford in 1922’, Last Post: A Literary Journal from the Ford Madox Ford Society, 1, 8 & 9 (Spring & Autumn, 2022), 1-19 (2). His essay concentrates on what Ford was writing, rather than publishing, in 1922.

[2] Penelope Fitzgerald, Charlotte Mew And Her Friends (1984; London: Flamingo, 2002), 209.

[3] Edith Wharton, Old New York (1924), in Novellas and Other Writings, edited by Cynthia Griffin Wolff (New York: Library of America, 1990), 467.

[4] The Selected Letters of D. H. Lawrence, compiled and edited by James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 284.

[5] Pound/Lewis: The Letters of Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis, edited by Timothy Materer (London: Faber and Faber, 1985), 138. His possible exceptions to this statement were the composer George Antheil and the writer Robert McAlmon.

[6] The Letters of D. H. Lawrence IV, June 1921–March 1924, edited by Warren Roberts, James T. Boulton and Elizabeth Mansfield (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 584. The term has since been applied to Arthur Ransome and J. L. Carr by their biographers, and to Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Daniel Wintle by himself. The day the other Lawrence (T. E., ‘of Arabia’) died, Forster was on his way to see him.

[7] John Clare, Journals, Essays, Journey from Essex, edited by Anne Tibble (Manchester: Carcanet New Press, 1980), 54.