(The Boppard Altarpiece, Panel: limewood, pine, paint & gilt: Victoria & Albert Museum)

Back in the day—not that day, another one—a woman had been on the throne of England for around sixty years.

Walk wide o’ the Widow at Windsor,

For ’alf o’ Creation she owns:

We ’ave bought ’er the same with the sword an’ the flame,

An’ we’ve salted it down with our bones.[1]

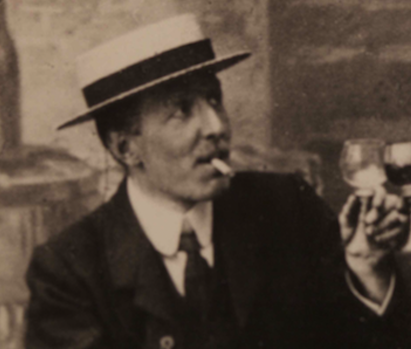

Yes, back then, a while and a world ago, when Queen Victoria was not quite gone, Rudyard Kipling had dropped in on the west coast of the United States. ‘There was wealth—unlimited wealth—in the streets’, he wrote of San Francisco, ‘but not an accent that would not have been dear at fifty cents.’ He was disappointed by the disparity between the fine and expensive clothes worn by the women he saw and their voices, ‘the staccato “Sez he”,“Sez I,” that is the mark of the white servant-girl all the world over.’

He felt, that is to say, that ‘fine feathers ought to make fine birds.’ But, ‘Wherefore, revolving in my mind that these folk were barbarians, I was presently enlightened and made aware that they also were the heirs of all the ages, and civilised after all.’ Luckily for this much-travelled traveller, he’s been accosted by ‘an affable stranger of prepossessing experience, with a blue and an innocent eye.’

It’s true that the man has peered into the hotel register and read ‘Indiana’ for the ‘India’ that Kipling has actually come from but, for the moment, the drinks and cigars that he presses upon the famous writer are welcome.[2]

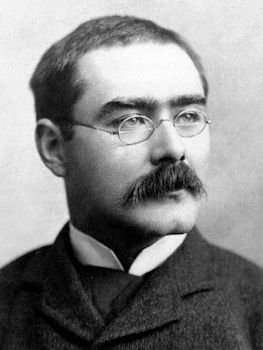

Ford Madox Ford referred numerous times to Kipling, often admiringly, but almost always—and, to me, unaccountably—focusing on the early work. Some of that is wonderful but the later stories, becoming often more complex, more oblique, more modernist, somehow get lost sight of, not only by Ford but by several other major writers of the time, as if Kipling were a known quantity and need not be kept any longer in sight.

But I was thinking mostly of that phrase tucked into the Kipling lines, which recurs several times elsewhere. ‘We are the heirs of all the ages,’ Ford wrote in early September 1913, in an essay which provided the ‘Preface’ to his Collected Poems a few weeks later and in which the same line sits.[3] He had written nearly a decade earlier of ‘all the dead Londons that have gone to the producing of this child of all the ages’, and in his 1910 novel, A Call, Grimshaw remarks to Pauline: ‘We’re the children of the age and of all the ages. . .’[4]

(Kipling/ Tennyson)

Those words look back to ‘Locksley Hall’—‘I the heir of all the ages, in the foremost files of time’—by Alfred Tennyson, a poet that Ford was generally unenthusiastic about, seeing him as one of the stifling ‘Victorian Great’ figures. Yet Tennyson’s work so saturated the second half of the nineteenth century that familiarity with it was unavoidable for any serious reader.[5]

It’s a point so obvious, so banal, so unremarkable, that huge numbers of people must fail utterly to remark it. We are the heirs, the inheritors, of all that has gone before. Not just the books, the music, the paintings—which people like me are only too ready to bang on about—but the housing, the streets, the scars on the landscape, what were the mining villages, what were the dockyards and shipyards, what were the council estates, the public libraries, the youth clubs, the community centres, the rivers, the fields and hedgerows, the birds and the butterflies, the very flavour of the air. And we are also the ones who will, in our turn, bequeath or pass on or let fall the things which others will inherit and be the heirs to. As far as we have influence and agency, what will our legacy to them look like?

After January—the first rule of that month being: survive January!—I venture a little further afield to gauge the State of Things. The news, astonishingly, is Not Good. For weeks, my main focus has been the life and letters of Ford Madox Ford in the 1920s, though, on occasion, I dipped my toes into world news, not wishing to have my leg taken off just above the knee by sharks should I venture too far in.

In the United States, things are evidently shaping up to be as bad as any sane person would expect, far worse, in fact. But there’s enough derangement here to satisfy any eager watchers at the gates of Bedlam, not least a government apparently possessed of a talent to choose every time precisely the wrong policy, facing in the the wrong direction and benefiting the wrong people.

On the bright side, though—O optimist!—the Chinese New Year celebrations have welcomed in the Year of the Snake, are still welcoming it, I suppose, since this involves not only animal but also zodiac elements. This is then the Year of the Wood Snake – also known as the Year of the Green Snake, wood being associated with the colour green. The Spring Festival, I gather, takes place over fifteen days, ending with the Lantern Festival on 12 February, and is estimated to be celebrated by some two billion people in numerous countries, not only China but Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam and their diasporas.

The snake may have had a bad press—certainly a bad Judaeo-Christian press—but I read that, in Chinese astrology, as a wood animal, it’s understood to represent good luck, renewal, flexibility, tolerance. Wood is good!

(‘Hippocamp’, a wooden carving in the form of a winged horse, originally part of the panelling inside Stafford Castle: Staffordshire County Museum Service)

This in turn brings to mind the recent piece following the death of David Lynch, which touched on Twin Peaks: The Return, and had a nice quote from Michael Horse, who played the series’ Deputy Sheriff Hawk: ‘When they did the premiere of The Return, the executives had not seen it, and they said: “Mr Lynch, would you say a few words?” And he comes out; he goes: “This project has a lot of wood in it. I like wood.”’

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2025/jan/23/an-oral-history-of-twin-peaks-david-lynch-madchen-amick-joan-chen

We all like wood, no? Wood nymphs, woodwind, woodbine, woodpeckers, woodlands – as a child, I had a pet woodlouse for a short time, though it didn’t end well. Woodcuts, wood engravings. Albrecht Dürer, Hiroshige, Käthe Kollwitz, Robert Gibbings, Thomas Bewick, Clare Leighton, David Jones, Gwen Raverat. Harriet Baker wrote of woodcuts made by Carrington and Vanessa Bell: ‘Carving directly into soft wood, the markings of tools and the tremors of hands were as much a part of the final pieces as form and composition.’[6]

The French historian Fernand Braudel gave wood a significant role in the lessening of the effects of the Black Death which, he argued, ‘did not, as used to be thought, arrive in Central Europe in the thirteenth century, but in the eleventh at the latest.’ His analysis of the retreat of the disease in the 18th century mentioned stone’s replacing wood in domestic architecture after major urban fires; the general increase in personal and domestic cleanliness, and the removal of small domestic mammals from dwellings, all factors that resulted in the lessening impact of fleas. He also discussed the enormous significance of wood being used everywhere: ‘One of the reasons for Europe’s power lay in its being so plentifully endowed with forests. Against it, Islam was in the long run undermined by the poverty of its wood resources and their gradual exhaustion.’[7]

(Thomas Gainsborough, A Forest Road: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge)

The gradual exhaustion of resources. Here we are again. Not so gradual now, I suspect, but in any case a phrase to tingle the tongues of those who, as previously noted, are custodians of the past and guardians of the future. Which is us, of course, even those currently making war on their own children and grandchildren.

In September 1911, Ezra Pound spent a Sunday afternoon with G. R. S. Mead, a scholar of hermetic philosophy, early Christianity and Gnosticism, the occult and theosophy: he had served as private secretary to Madame Blavatsky during her last years. He had founded the Quest Society in 1909 and invited Pound to give a lecture, which would be published subsequently in the quarterly review, The Quest. Pound delivered his lecture early in 1912 and it appeared in the October issue of the review with the title ‘Psychology and Troubadours’. Twenty years later, it was incorporated into Pound’s The Spirit of Romance.[8] It’s years since I read it but one sentence, particularly, lodged in my memory and remains intact: ‘We have about us the universe of fluid force, and below us the germinal universe of wood alive, of stone alive.’[9]

Pound, like Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Guy Davenport wrote, ‘had conceived the notion that cultures awake with a brilliant springtime and move through seasonal developments to a decadence. This is an ideas from Frobenius, who had it from Spengler, who had it from Nietzsche, who had it from Goethe.’[10]

Yes. Never mind third runways, never mind nuclear power stations on every corner, never mind mimicking anti-immigrant messages from other political parties that run on that sort of fuel. If a body is bleeding to death in front of you—how can I put this?—it may be best, before all else, to try to stop the bleeding.

Touch wood. Good wood. Touch good wood.

Notes

[1] ‘The Widow at Windsor’, Rudyard Kipling’s Verse: Inclusive Edition, 1885-1918 (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1925), 471.

[2] Rudyard Kipling, From Sea to Sea (2 volumes: Macmillan, 1900), I: 479-480

[3] Ford Madox Ford, ‘The Poet’s Eye’, New Freewoman, I, 6 (1 September 1913), 109; ‘Preface’ to Collected Poems (London: Max Goschen, 1914 [1913]), 20.

[4] Ford Madox Ford, England and the English, edited by Sara Haslam (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2003), 4; Ford Madox Ford, A Call: The Tale of Two Passions (1910; with an afterword by C. H. Sisson, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1984), 23.

[5] Alfred Tennyson, Poems: A Selected Edition, edited by Christopher Ricks (London: Longman, 1989), 192.

[6] Harriet Baker, Rural Hours: The Country Lives of Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Townsend Warner & Rosamond Lehmann (London: Allen Lane, 2024), 73.

[7] Fernand Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism, 15th – 18th Century. Volume I: The Structures of Everyday Life: The Limits of the Possible (London: Fontana Books, 1985). Translated from the French; revised by Sîan Reynolds, 83, 84, 363.

[8] Ezra Pound, Ezra Pound to His Parents: Letters 1895–1929, edited by Mary de Rachewiltz, David Moody and Joanna Moody (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 260; A. David Moody, Ezra Pound: Poet: A Portrait of the Man and His Work: Volume I: The Young Genius 1885–1920 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 159.

[9] Ezra Pound, The Spirit of Romance (1910; New York: New Directions, 1968), 92.

[10] Guy Davenport, The Geography of the Imagination (Boston: David R. Godine, 1997), 22.

.

.