(Tom Quad, Christ Church College)

‘Even when we protested the invasion of Iraq’, I said to the Librarian, recalling that day some twenty years earlier when we shuffled along London streets in company with over a million others, ‘I think we moved more quickly than this.’

‘This’ was our glacial progress up St Aldates in Oxford on a sunny afternoon, together with residents, tourists, American and other participants in the Oxford Experience, or those embarked upon the countless other summer courses and programmes, and many hundreds of—mainly Japanese—children dressed in the Gryffindor house colours of scarlet and gold, concerned to take in the Harry Potter vibrations from New College, the Bodleian Library and Christ Church College. Tour guides in their dozens hoisted small flags or halted in gateways with uplifted arms. Lanyards in their hundreds bobbed or swung. Some individuals, either on home turf or away, looked vague, a little stunned, reminding me of the passage in Rory Stewart’s memoir, where he described Steve Hilton, David Cameron’s director of strategy, moving into the corridor and another room. ‘He seemed to be searching for something – although I couldn’t tell whether it was a cat, an idea, or his shoes.’[1]

On High Street or Broad Street, Broad Walk, Christ Church Meadow, by rivers and canals, on bridges and benches, crowds ebbed and flowed – but mainly flowed. We are soon to be visible in a thousand physical or virtual photograph albums. I said, at one point, ‘Okay, if it’s a child of ten or younger having a photograph taken, we’ll pause. Otherwise, we plough straight on.’ The Librarian agreed but soon lowered the qualifying age to eight, then six. Minutes later, it was down to zero. Thereafter, we ploughed straight on.

(Alice Liddell’s dad, Henry George Liddell, dean of Christ Church from 1855)

Oxford! The literary references the word throws up are astonishing, even excluding the people that only studied there. Lewis Carroll, or rather, Charles Dodgson, haunts the place, but other names rampage through a distracted memory: Philip Pullman, Dorothy Sayers’ Gaudy Night, John Wain, P. D. James, Iris Murdoch, Hardy’s Jude and Colin Dexter’s Morse, C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien. A random footnote fact I gathered since that visit was that Edward De Vere, seventeenth Earl of Oxford, was educated not at Oxford, as one might reasonably expect, but at Queen’s College, Cambridge. Attempts were later made to claim him as the ‘real’ author of Shakespeare’s plays, an idea launched by the splendidly named John Thomas Looney. De Vere was the nephew of Arthur Golding, translator of Ovid, his Metamorphoses ‘the most beautiful book in the language’, in Ezra Pound’s words.[2] A man skilled in ‘fourteeners’ (that many syllables in a line):

Then sprang up first the golden age, which of it selfe maintainde,

The truth and right of every thing unforst and unconstrainde.

There was no feare of punishment, there was no threatning lawe

In brazen tables nayled up, to keep the folke in awe.

There was no man would crouch or creepe to Judge with cap in hand,

They lived safe without a Judge, in everie Realme and lande.

Here Daphne flees from Apollo:

And as shee ran the meeting windes hir garments backewarde blue,

So that hir naked skinne apearde behinde hir as she flue,

Hir goodly yellowe golden haire that hanged loose and slacke,

With every puffe of ayre did wave and tosse behind hir backe.[3]

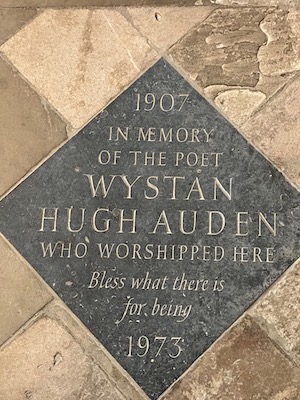

One name occurs on the ground as well as in the mind, the memorial plaque in Christ Church Cathedral (astonishing vaulted ceiling, stained glass by Burne-Jones and others, the St Frideswide Shrine). W. H. Auden came to the College to study biology, switched to English Literature in his second year and graduated (with a third class degree) in 1928. Nearly 30 years later, he became Oxford Professor of Poetry, and returned to Christ Church to live (part of the time) in 1972, the year before his death.

Wot, no Ford Madox Ford notes? Perhaps a sly one. In Some Do Not. . ., Christopher Tietjens, in a mood verging on ‘high good humour’, walks through a Kentish field with Valentine Wannop, a scene, a day, a walk which will recur in both their memories. Among those things that the best people must know are the local names (and the stories behind them) of the plants and flowers they pass. Tietjens—younger son, mathematician, member of the English public official class, who will also, in time, be lover, soldier and antique dealer—tells over to himself the words, the names, the language:

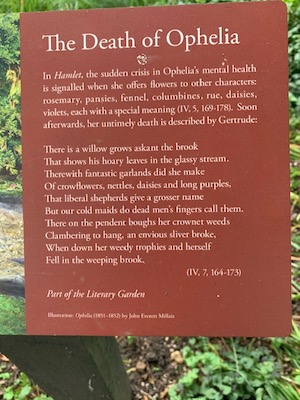

In the hedge: Our lady’s bedstraw: dead-nettle: bachelor’s button (but in Sussex they call it ragged robin, my dear: So interesting!) cowslip (paigle, you know, from the old French pasque, meaning Easter): burr, burdock (farmer that thy wife may thrive, let not burr and burdock wive!); violet leaves, the flowers of course over; black briony; wild clematis: later it’s old man’s beard; purple loose-strife. (That our young maids long purples call and liberal shepherds give a grosser name. So racy of the soil!) …[4]

In the wonderful Botanic Garden, the country’s oldest, one section is the Literary Garden, featuring plants that occur in literature, Alice in Wonderland, Agatha Christie (a great user of poisons) and others, including William Shakespeare:

Yes, those liberal shepherds grossly naming again. Modernists though Joyce, Eliot, Woolf, Wyndham Lewis and Ford were, they were not Futurists rejecting the past—a little more selective than that: ‘BLAST years 1837 to 1900’ and, indeed, ‘BLESS SHAKESPEARE for his bitter Northern Rhetoric of humour’—and they all had frequent recourse to that Elizabethan. . .

Notes

[1] Rory Stewart, Politics on the Edge: A Memoir from Within (London: Jonathan Cape, 2023), 100.

[2] Ezra Pound, The ABC of Reading (London: Faber and Faber, 1961), 127

[3] Extracts in The Oxford Book of Classical Verse, edited by Adrian Poole and Jeremy Maule (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 394; The Oxford Book of Verse in English Translation, Chosen and Edited by Charles Tomlinson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), 38.

[4] Ford Madox Ford, Some Do Not. . . (1924; edited by Max Saunders, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2010), 132.