‘Birth, and copulation, and death.

That’s all the facts when you come to brass tacks:

Birth, and copulation, and death.’

(Fragment of an Agon)[1]

Is T. S. Eliot’s Sweeney a little too concise here? You may be thinking, in some moods yes, in some moods no. You may even be thinking it a little too expansive. But most people, I suspect, might want to add a bit.

Take today, for instance, 17 December. The celebrated translator of Russian literature, Constance Garnett, died at 03:00 on this day in 1946. Over 70 English versions, of Turgenev, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Goncharov, Tolstoy. Dorothy Sayers, author of superb detective stories and translator of Dante, died in 1957, also on this day.

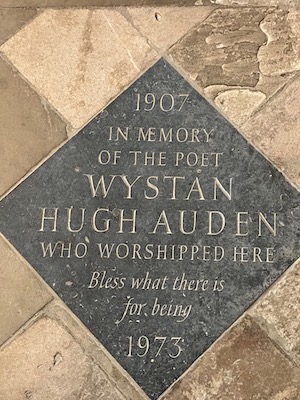

The middle term: throw in a wedding (and assume a positive). On 17 December 1914, the painter Paul Nash and Margaret Odeh—‘Bunty’—were married in St Martin-in-the-Fields by ‘the young pacifist vicar the Reverend Dick Sheppard.’[2] Cue the opening stanza of W. H. Auden’s Letter to Lord Byron:

Excuse, my lord, the liberty I take

In thus addressing you. I know that you

Will pay the price of authorship and make

The allowances an author has to do.

A poet’s fan-mail will be nothing new.

And then a lord—Good Lord, you must be peppered,

Like Gary Cooper, Coughlin, or Dick Sheppard.[3]

Gary Cooper, at least, will still be a familiar name; the other two, these days, rather less so, though not to historians of the 1920s and 1930s: Sheppard, the priest whose sermons, broadcast by the BBC, made him a national figure, and who later founded the Peace Pledge Union; Charles Coughlin, the Catholic priest who was also a widely-known broadcaster, though his anti-Semitic and pro-Fascist sympathies made his output rather different.

(Dick Sheppard broadcasting from St Martin-in-the-Fields: BBC)

On 17 December 1941, Sylvia Townsend Warner wrote to her friend Paul Nordoff: ‘Luckily, I have a tough memory for what I like, and I have most of it tucked away somewhere behind my ears.’[4] Just ten days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, then, a reminder if one were needed that on another 17 December—1903—Wilbur Wright’s fourth and last flight carried him 852 feet in 59 seconds.

The implications of that pioneering effort emerged with gradually increasing force and clarity a decade or so later. In 1915, Ezra Pound wrote to his parents (17 December): ‘Lewis has enlisted. That about takes the lot.’ He added: ‘I suppose we will go to France after the war. if it ever ends.’[5] Bombardier Wyndham Lewis would later recall that: ‘The war was a sleep, deep and animal, in which I was visited by images of an order very new to me. Upon waking I found an altered world: and I had changed, too, very much.’[6]

A few years on (17 December 1958) and the great Australian novelist Patrick White was writing to his friend and publisher Ben Huebsch—the rock on which White’s career was built, David Marr remarks—about his novel, Riders in the Chariot. ‘I shall want somebody here to check the Jewish parts after a second writing. I feel I may have given myself away a good deal, although passages I have been able to check for myself, seem to have come through either by instinct or good luck, so perhaps I shall survive. After all, I did survive the deserts of Voss.’ And in another letter to Huebsch, five months later, he returned to this: ‘What I want to emphasise through my four “Riders” – an orthodox refugee intellectual Jew, a mad Erdgeist [Earth spirit] of an Australian spinster, an evangelical laundress, and a half-caste aboriginal painter – is that all faiths, whether religious, humanistic, instinctive, or the creative artist’s act of praise, are in fact one.’[7] (I reread all Patrick White’s books seven years ago and I’m damned if I don’t feel almost ready to do it again. . .)

(Ford via New York Review of Books)

But then – why not celebrate? 17 December birthdays, yes: Humphry Davy, John Greenleaf Whittier, Erskine Caldwell, Paul Cadmus, Penelope Fitzgerald, Jacqueline Wilson, John Kennedy Toole – and the primary focus, or beginning spark, of all this anniversary rambling, Ford Madox Ford, 152 today.

His birthdays weren’t always joyous: at a party in 1901, he nearly choked on a chicken bone ‘and was prostrate for some days’.[8] In 1916, he was in a Red Cross Hospital in Rouen, writing to Joseph Conrad a couple of days later: ‘As for me—c’est fini de moi, I believe, at least as far as fighting is concerned—my lungs are all charred up & gone—they appeared to be quite healed, but exposure day after day has ended in the usual stretchers and ambulance trains’. In 1920, he spent at least a small portion of his birthday writing to Thomas Hardy, asking him to sign a manifesto protesting against British government policy in Ireland. It was published on 1 January 1921 in the Manchester Guardian and other papers. Fifty writers, artists and academics signed it but Thomas Hardy was not among them.

Past lives, past struggles, victories, defeats. Surely there is comfort to be found there, that they were faced with things we recognise only too well—not only the individual battles but the more general ones, against Fascism, vicious racism, authoritarianism, the hijacking of news, of the sources of information, the assaults on free speech, on civil liberties, on democratic rights—and came through. And we?

Optimism, pessimism. One up, one down; Monday, Tuesday; left hand; right hand. I liked Guy Davenport on the judicious estimate of his own make-up, reporting to Hugh Kenner that his friend Steve Diamant’s photographs included one that served as the author photograph on the dust jacket of Tatlin!, Davenport’s first collection of stories, or assemblages: ‘Guy beaming in the Dionysian priest’s chair, the Theatre, Athens. I had no notion such a radiant smile was in me. It cured a third of my paranoia and an eighth of my Calvinist pessimism to see it.’[9]

A whole eighth. Some photograph, some smile.

Notes

[1] T. S. Eliot, The Complete Poems and Plays (London: Faber and Faber, 1969), 122.

[2] Ronald Blythe, First Friends: Paul and Bunty, John and Christine – and Carrington (London: Viking, 1999), 77; David Boyd Haycock, A Crisis of Brilliance (London: Old Street Publishing, 2009), 238-9.

[3] W. H. Auden, The English Auden: Poems, Essays and Dramatic Writings, 1927-1939, edited by Edward Mendelson (London: Faber, 1977), 169.

[4] Sylvia Townsend Warner, Letters, edited by William Maxwell (London: Chatto & Windus, 1982), 76.

[5] Ezra Pound, Ezra Pound to His Parents: Letters 1895–1929, edited by Mary de Rachewiltz, David Moody and Joanna Moody (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 358.

[6] Wyndham Lewis, Rude Assignment: A narrative of my career up-to-date (London: Hutchinson, 1950), 129.

[7] Patrick White, Letters, edited by David Marr (London: Jonathan Cape, 1994), 151, 153. Marr’s remark about Huebsch’s importance is in ‘The Cast of Correspondents’, 638.

[8] Arthur Mizener, The Saddest Story: A Biography of Ford Madox Ford (London: The Bodley Head, 1972), 73.

[9] Questioning Minds: The Letters of Guy Davenport and Hugh Kenner, edited by Edward M. Burns, two volumes (Berkeley: Counterpoint Press, 2018), I, 630.