(C. R. W. Nevinson, Any Wintry Afternoon in England: Manchester Art Gallery)

Walking on the wide path in the park, I see a football rolling determinedly towards me over the grass, two boys watching, a long way off. I trap it, nudge and kick. It travels a fair distance but nowhere near the waiting boys. A woman walking towards me on the path says: ‘One of my irrational fears, a ball coming at me like that.’ I say: ‘One of mine too now’, and she laughs. ‘Oh, you did okay.’

Did I, though? Not the kick, that was what it was but. . . irrational fears? If it were now one of mine because of that episode, it’s not irrational but quite rational, reasoned, based on solid, empirical evidence, so. . .Don’t overthink it! the Librarian says, often in person and now in my head. Don’t overthink things!

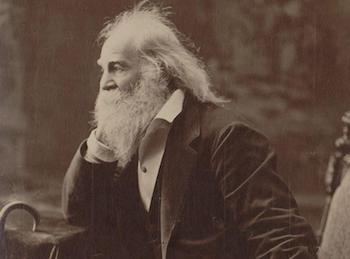

Ding, ting, chose, cosa, peth, rud, shay, hlutur: thing. . . ‘The distinguished thing’ was Henry James’s famous phrase for death. Did he actually say it? Following a reference to Edith Wharton’s A Backward Glance, I see that there’s an extra link or two: ‘He is said to have told his old friend Lady Prothero, when she saw him after the first stroke, that in the very act of falling (he was dressing at the time) he heard in the room a voice which was distinctly, it seemed, not his own, saying: “So here it is at last, the distinguished thing!”’ Wharton adds: ‘The phrase is too beautifully characteristic not to be recorded.’[1] It’s certainly wonderfully—and characteristically—indefinite, or at least, on a very convoluted path: ‘He is said’ to have told someone else that he heard a voice which wasn’t his own, the word ‘distinctly’ applied only to a negative, ‘not his own’ and, even then, ‘it seemed’.

(Edith Wharton via BBC)

Death as ‘the thing’ (Death! Where is thy thing?) – while for Edna St Vincent Millay, death was not the thing but the force engulfing it:

Death devours all lovely things:

Lesbia with her sparrow

Shares the darkness,—presently

Every bed is narrow.[2]

The line ‘Every bed is narrow’ I take to refer to coffins (rather than, or as well as, singleness or separation), and it also recalls Pound’s ‘Homage to Sextus Propertius’. ‘We, in our narrow bed, turning aside from battles:/ Each man where he can, wearing out the day in his manner.’[3]

And yet – I was thinking, at the outset, more of things than of death; or rather, words and things, particularly the word ‘thing’. Impressively, its origin seems to embrace both ‘object’ and ‘parliament’. The definitions are lavish: an assembly, court, council, matter, affair, problem, fact, event, action, that which exists or can be thought of, a living creature, a piece of writing; in the plural, clothes, personal belongings. What a word, what a world, ‘thing’ is!

While an inmate of the Disciplinary Training Center at Metato, north of Pisa, in the autumn of 1945, Ezra Pound wrote:

And for all that old Ford’s conversation was better,

consisting in res non verba,

despite William’s anecdotes, in that Fordie

never dented an idea for a phrase’s sake

and had more humanitas [4]

Things, not words for things. Pound was reiterating his belief in those opposing—or complementary—positions, Ford as realist, Yeats as symbolist, that he proposed on more than one other occasion.[5] Poignantly, they were both just six years dead – the length of a world war, say.

That ‘humanitas’ had led the youthful Ford to rashly discuss the conditions of the London poor with a young woman he took out in a boat, only to be reproved the next day by her mother, Lady Cusins: ‘“Fordie, you are a dear boy. Sir George and I like you very much. But I must ask you not to talk to dear Beatrice … about Things!”’[6]

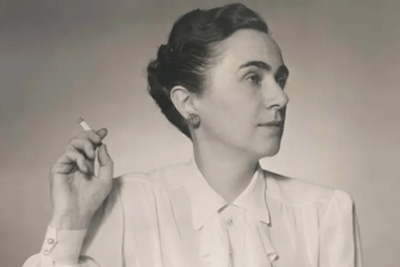

(Iris Barry)

Ford had actually written to Iris Barry (4 July 1918): ‘I have always been preaching to people not to write “about” things but to write things—& you really do it—so I like to flatter myself that you are an indirect product of my preachings—a child of my poor old age.’ (He was still serving in the British Army, having by then reached the ‘poor old age’ of 44.)[7]

Ralph Waldo Emerson also fished in those waters: ‘The corruption of man is followed by the corruption of language’ and ‘new imagery ceases to be created, and old words are perverted to stand for things which are not’. But ‘wise men pierce this rotten diction and fasten words again to visible things’.[8] This linking of words and things would have some later commentators and theorists tearing their hair out, words for them being quite arbitrary marks on the page, the word for something not otherwise linked to that something. Lord Byron though, as so often, pursued his own path:

But words are things, and a small drop of ink,

Falling like dew upon a thought, produces

That which makes thousands, perhaps millions, think.[9]

And as if by magic, an email just arrived from PN Review offers, from its archive, ‘Holà’, a short poem by C. H. Sisson from 1992, which is also concerned with words and things:

Words do not hold the thing they say:

Say as you will, the thing escapes

Loose upon air, or in the shapes

Which struggle still before the eyes.

Holà will run upon its way

And never catch up with its prize.[10]

Later in my park walk, halfway down a steepish path, I see a woman ahead of me with a child in a pushchair and a dog crouched in the grass nearby, with a ball in its mouth. It looks at me inquiringly. ‘I’m afraid not’, I say. ‘You’re not my dog and that ball is covered with slobber, as we both know.’ The woman is partly blocking the path where it meets the wider track, talking on her phone and with her back to me, but moves to one side as I approach. The dog lies down close by her and lets the ball drop from its mouth. She half-turns and kicks the ball, which rockets cleanly away for a good distance – and apparently just where she meant it to go. Damn, I think, she only needed to be a bit better than me to make the point. What point? That I shall not overthink it. . .

Notes

[1] Edith Wharton, Novellas and Other Writings: Madame de Treymes, Ethan Frome, Summer, Old New York, The Mother’s Recompense, A Backward Glance, edited by Cynthia Griffin Wolff (New York: Library of America, 1990), 1055.

[2] Millay, ‘Passer Mortuus Est’ (first of three stanzas), in F. O. Matthiessen, The Oxford Book of American Verse (New York: Oxford University Press, 1950), 886. As is often noted, Millay here references Catullus 2, about the death of his lover Lesbia’s sparrow, her ‘plaything’: The Poems of Catullus, translated with an introduction by Peter Whigham (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1966), 52.

[3] Ezra Pound: Poems and Translations, edited by Richard Sieburth (New York: Library of America, 2003), 535.

[4] Canto LXXXII, The Cantos of Ezra Pound, fourth collected edition (London: Faber and Faber, 1987), 525. I have tried—and failed—to insert the ideogram, ‘jen’.

[5] Ezra Pound, Polite Essays (1937; Plainview, New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1966), 50; Pound/ Williams: Selected Letters of Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams, edited by Hugh Witemeyer (New York: New Directions, 1996), 187.

[6] Ford Madox Ford, Return to Yesterday: Reminiscences 1894-1914 (London: Victor Gollancz, 1931), 75.

[7] Ford Madox Ford, Letters of Ford Madox Ford, edited by Richard M. Ludwig (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965), 87.

[8] Ralph Waldo Emerson, Selected Essays, edited by Larzer Ziff (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1982), 51.

[9] Lord Byron, Don Juan, III:88, edited by T. G. Steffan, E. Steffan and W. W. Pratt (London: Penguin Books, 1996), 182.

[10] PN Review 87 (September–October 1992), 28.