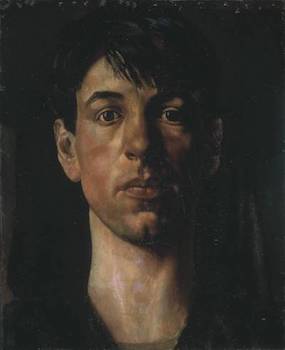

John Buchan in the library

https://archives.queensu.ca/exhibits/buchan/family

‘You may say that everyone who had taken physical part in the war was then mad’, Ford Madox Ford wrote a dozen years after the Armistice. Objects that ‘the earlier mind labelled as houses’, that had seemed to be ‘cubic and solid permanences’, had been revealed as thin shells that could be crushed like walnuts, he went on. ‘Nay, it had been revealed to you that beneath Ordered Life itself was stretched, the merest film with, beneath it, the abysses of Chaos. One had come from the frail shelters of the Line to a world that was more frail than any canvas hut.’[1]

In John Buchan’s Huntingtower (1922), the poet John Heritage remarks to Dickson McCunn, ‘I learned in the war that civilization anywhere is a very thin crust.’[2] And here is Andrew Lumley in The Power-House: ‘“You think that a wall as solid as the earth separates civilisation from barbarism. I tell you the division is a thread, a sheet of glass. A touch here, a push there, and you bring back the reign of Saturn.”’[3]

On the face of it, the two novelists could hardly appear less alike, one a modernist with a markedly artistic background, whose work sold poorly for most of his life; the other a hugely successful writer of popular fiction, keen sportsman, son of a minister of the Free Church of Scotland, very traditional, a seemingly paradigmatic establishment figure: Lord Tweedsmuir, Governor General of Canada, born in Perth on this day, 26 August, 1875. Still, they were almost exact contemporaries: Buchan published his first book at the age of nineteen—Ford’s was published shortly before his eighteenth birthday—and produced more than a hundred in total (as against Ford’s eighty). I’ve read around a quarter of Buchan’s titles, ten of them more than once, I see. The ‘shockers’ like The Thirty-Nine Steps are by far the best-known but those made up a relatively small part of Buchan’s huge output: even fiction comprises barely one-third of it.

(Izaak Walton: Dean & Co © National Portrait Gallery, London)

In a more detailed sense, even confining the matter to Huntingtower, a reader infected with the Ford Madox Ford virus might be pencilling faint marks in the margin against such lines as ‘Finally he selected Izaak Walton’ and ‘the seeing eye’ (16), ‘Poetry’s everywhere, and the real thing is commoner among drabs and pot-houses and rubbish-heaps than in your Sunday parlours’ (26)[4] and ‘a white cottage in a green nook’ (31), as well as the editor’s citing of a passage in Buchan’s autobiography dealing with his feelings about the war (xx). Buchan writes there, ‘I acquired a bitter detestation of war, less for its horrors than for its boredom and futility, and a contempt for its panache. To speak of glory seemed a horrid impiety.’[5]

Before all else, Buchan writes a rattling good yarn and I enjoy his books enormously for themselves. Those thrillers and adventure stories and romances largely achieve exactly what they set out to do, while their limitations are fairly obvious, not least to Buchan himself. Writing to his sister Anna about her second novel The Setons (she wrote under the name of O. Douglas), Buchan remarked: ‘In Elizabeth you draw a wonderful picture of a woman (a thing I could about as much do as fly to the moon).’[6]

Oh Carroll! (character added by Hitchcock) https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38053736

Of course, hundreds of other writers have written rattling good yarns, made a living and duly faded from view; but many of Buchan’s books have not only survived but seem to be in a state of constantly improving health. They certainly possess qualities or contain features, often hard to pin down and specify, which have enabled that continued vitality. David Daniell refers to Buchan’s writing novels ‘with a mixture of surface pace of action and a deeper density of content which have a timeless quality’.[7]

For me, one of the pleasures is noticing the many ways in which a writer superficially so different from the usual modernist cast list overlaps with them, inhabits a recognisably similar world. His writing may be aimed at an audience quite unlike those aimed at by Joyce or Woolf or Ford; and he may not be fragmenting narratives or operating tricky timeframes or incorporating extra-literary discourses or multilingual puns but the overlap is certainly there for me.

This is largely because much of his work is set in and around the First World War, particularly in the years following it, perhaps my main area of interest. And although Buchan himself inhabited a world of prominent political and diplomatic figures, there remained a touch of the outsider, not least because of the war. Rejected for the army on grounds of both age and health, he visited France and Flanders as correspondent for The Times and took increasingly senior roles in information and intelligence but, as Andrew Lownie writes, Buchan ‘emerged from the First World War physically and emotionally shattered. Many of his closest friends had been killed and this loss of his immediate circle reinforced his sense of being displaced.’[8]

A good deal of his writing, then, is concerned with the terrain that most engages me: with the effects of the war both on individuals who were actively engaged in the fighting and those who were not, with shifting perceptions and understanding of shell-shock, with radical jolts in social relations, the rising threat of fascism, the ‘new Vienna doctrine’ and shifts in fashion and femininity, as the Edwardian ‘hourglass’ shape was replaced with the ‘tubular look’.[9]

https://www.collectorsweekly.com/

This last is an example of the fascinating detail that can be followed for a short stretch or for many, many miles. While there is never (to my mind) any convincing strain of homoeroticism, here in Huntingtower is Saskia: ‘her slim figure in its odd clothes was curiously like that of a boy in a school blazer’ (70); in Mr Standfast, Mary is described as moving ‘with the free grace of an athletic boy’.[10] In John Macnab, Janet’s face ‘had a fine hard finish which gave it a brilliancy like an eager boy’s’ and later she looks to Sir Archie ‘like an adorable boy.’[11] Finally, in The Dancing Floor, Mollie Nantley says of Koré that she is ‘utterly sexless – more like a wild boy’, while Leithen reflects that, ‘These children [both youths and girls] looked alert and vital like pleasant boys, and I have always preferred Artemis to Aphrodite.’[12]

Artemis: virginal, eternally young, independent of men, athletic, the huntress. In C. E. Montague’s Rough Justice, Molly, ‘the young Artemis’, has a job as ‘games mistress’,[13] as does Valentine Wannop in Ford’s A Man Could Stand Up–, though a good many other male novelists and poets of the period would far rather, I think, have embraced Aphrodite. Trudi Tate mentions Lawrence and Faulkner as seeming ‘to disapprove of these androgynous figures’,[14] and one would immediately add Joyce. All non-combatants, I notice, which is either irrelevant or a thought for another time.

Writing of her single meeting with Buchan in the summer of 1932, Catherine Carswell, novelist and friend (and biographer) of D. H. Lawrence, observed that, ‘A traditionalist in so many respects, he was yet a champion of the modern girl, delighting in her independences, even in her defiances, frowning neither upon her sometimes extravagant make-up nor upon her occasions for wearing trousers. As among the goddesses, his preference was for Artemis.’[15]

Ah, the modern girl. In The Dancing Floor (213), Buchan writes: ‘Virginity meant nothing unless it was mailed, and I wondered whether we were not coming to a better understanding of it. The modern girl, with all her harshness, had the gallantry of a free woman. She was a crude Artemis, but her feet were on the hills. Was the blushing, sheltered maid of our grandmother’s days no more than an untempted Aphrodite?’

Buchan is not a modernist novelist and not a part of any literary movement, though he doesn’t seem as wholly removed from the literary world as Kipling, who sometimes seems not to have known any writers other than Rider Haggard. Buchan and his wife knew Elizabeth Bowen, Rose Macaulay, Hugh MacDiarmid, Walter de la Mare, Robert Graves, T. E. Lawrence – and Virginia Woolf, whose novels Buchan admired. Woolf had known Buchan’s wife Susan for many years and one of her last letters was written to Susan, though unposted: Leonard Woolf sent it on in the month following Virginia’s death.[16]

There have, naturally, been recurrent complaints about Buchan as racist, anti-Semitic, sexist: the usual fare. There have been equally recurrent rebuttals and, indeed, what a lot of it comes down to seems to be complaints that people a hundred years ago didn’t wholly share the social attitudes that we – that most of us, we hope – share today. Still, one clue to his books lasting is, I suspect, the way that certain artists fall out of fashion because of their content or attitudes or language but then, after a further period of time has elapsed, come into focus again, far enough back now to be viewed objectively and enjoyed without fretting about ‘relevance’ or current orthodoxies. Here’s Graham Greene, looking back to the 1930s:

‘An early hero of mine was John Buchan, but when I re-opened his books I found I could no longer get the same pleasure from the adventures of Richard Hannay. More than the dialogue and the situation had dated: the moral climate was no longer that of my boyhood. Patriotism had lost its appeal, even for a schoolboy, at Passchendaele, and the Empire brought first to mind the Beaverbrook Crusader, while it was difficult, during the years of the Depression, to believe in the high purposes of the City of London or of the British Constitution. The hunger-marchers seemed more real than the politicians. It was no longer a Buchan world.’[17]

Not a Buchan world; yet, although the attitudes towards the threats may have changed over the years, some of the current threats themselves—the threat of fascism, attempts to subvert democracy, ‘fake news’ (that blood relation of propaganda)—seem worryingly familiar. But, alas, Richard Hannay, Edward Leithen, Sandy Arbuthnot and Archie Roylance will not be saving us this time around.

References

[1] Ford Madox Ford, It Was the Nightingale (London: Heinemann, 1934), 48, 49.

[2] John Buchan, Huntingtower (1922; edited by Ann Stonehouse, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 116.

[3] John Buchan, The Power-House (1916; Edinburgh: B&W Publishing, 1993), 38.

[4] See Ford Madox Ford on ‘the portable zinc dustbin’, in the ‘Preface’ to Collected Poems (London: Max Goschen, 1913 [dated 1914]), 16-17.

[5] John Buchan, Memory Hold-the-Door (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1940), 167.

[6] Quoted by Janet Adam Smith, John Buchan: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 284.

[7] David Daniell, The Interpreter’s House: A Critical Assessment of the Work of John Buchan (London: Thomas Nelson, 1975), 209.

[8] Andrew Lownie, John Buchan: The Presbyterian Cavalier (London: Constable, 1995), 297.

[9] Martin Pugh, ‘We Danced All Night’: A Social History of Britain Between the Wars (London: The Bodley Head, 2008), 171.

[10] John Buchan, Mr Standfast (1919; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993, edited by William Buchan), 11.

[11] John Buchan, John Macnab (1925; edited with an introduction by David Daniell, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 125, 182.

[12] John Buchan, The Dancing Floor (1926; edited with an introduction by Marilyn Deegan, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 57, 51.

[13] C. E. Montague, Rough Justice (London: Chatto & Windus 1926), 171.

[14] Trudi Tate, Modernism, History and the First World War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), 115n.

[15] Catherine Carswell, ‘John Buchan: A Perspective’, in John Buchan by His Wife and Friends (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1947), 160.

[16] Virginia Woolf, Leave the Letters Till We’re Dead: Collected Letters VI, 1936-41, edited by Nigel Nicolson and Joanne Trautmann Banks (London: The Hogarth Press, 1994), 483 and n.

[17] Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (London: Vintage, 1999), 69.