In Pavannes and Divisions, his prose collection of June 1918, Ezra Pound included ‘A Retrospect’, a group of ‘early essays and notes’, gathered from a period of some four or five years. Towards the close, under the heading ‘Only Emotion Endures’, Pound wrote: ‘Surely it is better for me to name over the few beautiful poems that still ring in my head than for me to search my flat for back numbers of periodicals and rearrange all that I have said about friendly and hostile writers.’[1]

The poets he names are, for the most part, predictable: Yeats, William Carlos Williams, Richard Aldington, H. D., Ford Madox Ford, James Joyce; and, of course, T. S. Eliot (‘I am almost a different person when I come to take up the argument for Eliot’s poems’). Two others are rather less expected: Alice Corbin, for instance, who, as well as a poet, was associate editor of Poetry magazine, for which Pound served as foreign correspondent, writing to her often in the 1912-1917 period.[2] He mentions her ‘One City Only’, which he himself published in his Catholic Anthology, 1914-1915. The second he alludes to—‘another ending “But sliding water over a stone”’—is ‘Love me at last’, published in Poetry in December 1914:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/browse?contentId=12993

The other slightly surprising inclusion is Padraic Colum—surprising, I mean, because, once again, this is a poet with a very traditional style yet with an evident appeal to Pound, even though he has been through the Imagist and Vorticist periods and publishes early versions of the first three Cantos in the summer of 1917. Indeed, it’s Colum whom he names first of all: ‘The first twelve lines of Padraic Colum’s “Drover”; his “O Woman shapely as a swan, on your account I shall not die”’.

The ‘first twelve lines’ of Colum’s ‘A Drover’ are:

To Meath of the pastures,

From wet hills by the sea,

Through Leitrim and Longford

Go my cattle and me.

I hear in the darkness

Their slipping and breathing.

I name them the bye-ways

They’re to pass without heeding.

Then the wet, winding roads,

Brown bogs with black water;

And my thoughts on white ships

And the King o’ Spain’s daughter.

Very simple; the kind of inversion (‘Go my cattle and me’) that you’d expect to set Pound’s teeth on edge. Yet this is quite skilled stuff: the subtle lengthening of lines to avoid the thud of the metronome; a light alliteration that never hits you over the head; the varies use of feminine line-endings; the twelfth line’s hint at a traditional children’s rhyme. Another twenty-four lines, though, beginning: ‘O! farmer, strong farmer!’ are less appealing, a bit more prone to poeticism and cliché.

The other poem, ‘I Shall Not Die’, begins:

O woman, shapely as the swan,

On your account I shall not die:

The men you’ve slain — a trivial clan —

Were less than I.

I ask me shall I die for these —

For blossom teeth and scarlet lips —

And shall that delicate swan-shape

Bring me eclipse?[3]

The swan, Michael Ferber notes, ‘has long been one of the most popular birds in poetry, not least because of the association of swans with poets themselves.’[4] There has certainly been an astonishing procession of literary swans, hardly surprising if the swan is the bird both of Apollo (god of poetry and music) and of Venus, goddess of love: from classical literature through to Shakespeare (the swan of Avon), Pope, Shelley, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and others. Among modern poets, the poet of swans is surely Yeats, who draws on the complex mythological links between Leda, Helen of Troy— long a Yeatsian symbol for Maud Gonne—and Clytemnestra in ‘Leda and the Swan’.[5] A swan is there too in that volume’s title poem, ‘The Tower’ when, mindful of death (in a section beginning ‘It is time that I wrote my will’), Yeats writes of ‘the hour’

When the swan must fix his eye

Upon a fading gleam,

Float out upon a long

Last reach of glittering stream

And there sing his last song.

Perhaps most memorable is the title poem of the wonderful 1919 volume, The Wild Swans at Coole. The weight and balance of those lines, ostensibly unremarkable language, in five six-line stanzas:

The trees are in their autumn beauty,

The woodland paths are dry,

Under the October twilight the water

Mirrors a still sky;

Upon the brimming water among the stones

Are nine-and-fifty swans.

There are phrases in this poem that echo lines in ‘Easter 1916’, which will appear in Michael Robartes and the Dancer in 1921 but which Yeats himself dates ‘September 25, 1916’—he held it back for political rather than poetical reasons.[6]

(Yeats and Lady Gregory, Coole Park, 1915: http://yeats2015.com/event/major-exhibition-explores-w-b-yeats-connections-with-the-west/ )

The attractions of the swan for the poet are evident enough, I think: its colour, the purity of whiteness but with that intense dash of black and yellow on its bill; the grace of the curve and sweep of its body and wings and neck, the extraordinary spectacle of its landing on water; the size and strength and grandeur of it; the long history, traditions, myths and symbols attached to the bird: in brief, beauty and transformation.[7]

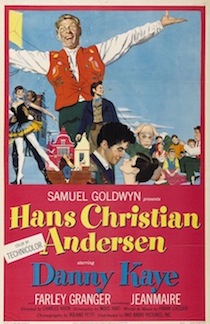

Transformation. I have a vague childhood memory of Danny Kaye, who’d starred as the title character in the 1952 Hollywood musical, Hans Christian Anderson, singing one of the songs from the film: ‘The Ugly Duckling’. There was an album of the songs released subsequently but I may simply have heard it played on the radio: it was internationally successful at the time. The duckling outsider turns out, of course, to be a very fine swan indeed (‘Me, a swan?’ ‘I am a swan’).

In 1959, Ezra Pound wrote from Rapallo to William Cookson, who had just launched, in close association with Pound, Agenda, the highly influential poetry magazine (still current). At the top of the letter is a suggested ‘Motto for Agenda No 3 or 4’: ‘How can anyone go antisemite in a world that contains Danny Kaye’.[8]

I picture Cookson opening that letter and reading that line; then lowering his forehead to beat it softly but repeatedly against the desktop. But perhaps not.

References

[1] Reprinted in Literary Essays of Ezra Pound, edited by T. S. Eliot (London: Faber & Faber, 1960), 14: all quotations from the same page.

[2] See The Letters of Ezra Pound to Alice Corbin Henderson, edited by Ira B. Nadel (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993).

[3] Selected Poems of Padraic Colum, edited by Sanford Sternlicht (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1989), 41-42, 24.

[4] Michael Ferber, A Dictionary of Literary Symbols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 214.

[5] See A. Norman Jeffares, A New Commentary on the Poems of W. B. Yeats (London: The Macmillan Press, 1984), 247-249.

[6] Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats (London: Macmillan London Ltd., 1950), 223, 147, 204. ‘Easter 1916’, though privately printed in an edition of twenty-five, ‘stayed out of public circulation’ until its publication in the New Statesman (23 October 1920): see R. F. Foster, W. B. Yeats: A Life. II. The Arch-Poet (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 58-64.

[7] On the complex, often destructive—and class-ridden—history of the swan, see Mark Cocker and Richard Mabey, Birds Britannica (London: Chatto & Windus, 2005), 60-69.

[8] ‘Some Letters to William Cookson 1956-1970’, Agenda, 17, 3-4 — 18, 1 (3 issues: Autumn-Winter-Spring, 1979/80) ‘Twenty-First Anniversary Ezra Pound Special Issue’, 39.