Writing of Felix Vallotton and what, he suggests, ‘might be called Vallotton’s law: that the fewer clothes a woman has on in his paintings, the worse the result’, Julian Barnes notes that ‘Vallotton came to the nude through a study of Ingres, proving that great painters, like great writers – Milton, famously – can be pernicious influences.’[1]

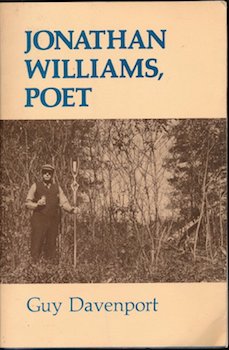

I came across this shortly after recalling Jonathan Williams quoting Bentley’s clerihew (‘The digestion of Milton/ Was unequal to Stilton/ He was only feeling so-so/ When he wrote Il Pensoroso’).

And then, a few days ago, waiting for the kettle to boil, I was browsing through a Penguin Classics translation of Virgil’s Eclogues, which had found its way onto the kitchen table, . The notes to the first eclogue mentioned two lines in Milton’s Lycidas derived from this single line of Virgil: ‘siluestrem tenui Musam meditaris auena’, translated there as ‘You meditate the woodland Muse on slender oat’.[2]

Already in trouble and the tea not even made. Mediate on, surely. But then my dictionary actually includes the phrase ‘meditate the muse’, offering as explanation ‘(Latinism, after Milton) to give one’s mind to composing poetry.’ The line in Lycidas does indeed have ‘meditate’ unclothed by a preposition. ‘Slender oat’? A reed pipe, perhaps oat grass, a wild grass that looks like the oat. The old Loeb edition’s version—‘wooing the woodland Muse on slender reed’—is a bit clearer at first glance.

Anyway: Williams, Barnes, Virgil. Three times so close together may be enemy action for Ian Fleming’s Goldfinger; it’s a sign from the gods for the rest of us. So, diverting my attention from ornithology, weird cat behaviour in the garden and university staff strikes, I thought back over the history of my problem with Milton.

One of the great poets, no doubt, no doubt. In the nineteenth century, it seems, few had a bad word to say about him – Blake, Wordsworth, Byron, Keats. In the twentieth century, things went the other way. Ezra Pound—to choose one of his more polite remarks—thought Milton ‘got into a mess trying to write English as if it were Latin.’[3] Enlarging on this elsewhere, he asserted that Milton was using ‘an uninflected language as if it were an inflected one, neglecting the genius of English, distorting its fibrous manner’.[4]

T. S. Eliot took William Hazlitt to task for classifying Dryden and Pope as ‘the great masters of the artificial style of poetry in our language’ as against his chosen poets of the ‘natural’ style: Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare and Milton. Reviewing ‘at least four crimes against taste’ that Hazlitt has committed in a single sentence, Eliot observes that ‘the last absurdity is the contrast of Milton, our greatest master of the artificial style, with Dryden, whose style (vocabulary, syntax, and order of thought) is in a high degree natural.’ Eliot is here reviewing a book on Dryden and has more to say on the respective strengths of the two poets but clearly, at this stage (1921, the year before The Waste Land), he finds more to admire in Dryden, whose powers were, he suggests, ‘wider, but no greater, than Milton’s’.[5] Pound comments that ‘Dryden gives T. S. E. a good club wherewith to smack Milton. But with a modicum of familiarity or even a passing acquaintance with Dante, the club would hardly be needed.’ This is turn looks back to Pound’s earlier comment that ‘Dante’s god is ineffable divinity. Milton’s god is a fussy old man with a hobby.’[6]

There are other famous negatives (F. R. Leavis, for one) but none of this has much bearing on my own troubles with Milton. The failure to warm to him, if failure it be, is obviously mine – still, I’m tempted to shovel a good part of the blame onto my old English master, a real Milton enthusiast. That enthusiasm drove him to read Paradise Lost to us, fairly relentlessly, for what seemed an eternity, an approach that drove some pupils to despair, rebellion or the edge of madness; for me, evidently, it erected barricades. ‘For each man kills the thing he loves’ – kills it for other people, in some cases, however good the intentions. I’ve made at least two serious attempts to get back into some sort of relationship with Mr Milton, one of them after reading Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, Pullman being such a strong advocate for Milton, and for Paradise Lost in particular. But it never really took.

Lycidas, though. A relatively short poem. A very literary one too, in the sense of adopting (even if tweaking) a good many conventions; and also retrospectively, since it’s been plundered for a good many book titles and quotations that everyone knows (even when they don’t, quite)—‘Fame is the spur’, ‘Look homeward angel’, ‘Tomorrow to fresh woods and pastures new’. I’ve read it several times, starting, of course, at school. But, as far back as I can remember, even reading Milton’s shorter poems was somehow associated with a sense of task, of obligation. I don’t mind putting in the work but didn’t really experience the pleasure which I thought a reasonable, reciprocal part of the deal.

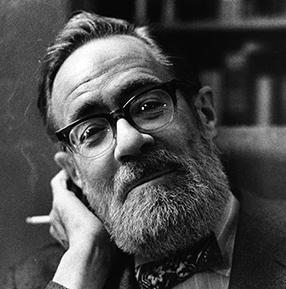

One sidelong approach is by way of John Berryman’s fine short story, ‘Wash Far Away’, which I read again recently. The title comes, of course, from Lycidas: ‘Whilst thee the shores and sounding Seas/ Wash far away, where ere thy bones are hurld’. The poem is a pastoral elegy, occasioned by the death of Edward King, a Cambridge friend of Milton, drowned in the Irish Sea. In Berryman’s story, a professor teaches Lycidas to his class, and the narrative of loss and lament in the poem is juxtaposed with the professor’s own memories and enduring sense of loss of a brilliant and gifted friend who died young. There’s a good deal of quite scholarly Miltonic discussion. Much of it circles around the question of whether the poem is actually ‘about’ King or, in fact, more about Milton himself. Several remarks by the students are surprisingly acute and unsettling—‘The professor studied the lines. He felt, uneasily, as if he had never seen them before’—but the effects of the session are finally positive, the sharpness of memories and the acute sense of loss, brought vividly to mind, seeming to resuscitate the professor, to bring alive again his image of himself as a sentient, emotionally responsive being.[7]

So I glance again, though warily, warily, at my copy of Paradise Lost, glowering in the corner. Ars longa, vita brevis, as someone – was it Seneca? – said. Well, yes – but just how longa? And just how brevis?

References

[1] Julian Barnes, ‘Vallotton: The Foreign Nabi’, in Keeping an Eye Open: Essays on Art (London: Jonathan Cape, 2015), 190.

[2] Virgil The Eclogues, translated by Guy Lee (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1984), 31, 109n. The lines in Lycidas are ‘and strictly meditate the thankless muse’ and ‘But now my oat proceeds’.

[3] Ezra Pound, How To Read (London: Desmond Harmsworth, 1931), 55.

[4] Ezra Pound, ‘Notes on Elizabethan Classicists’, in Literary Essays of Ezra Pound, edited by T. S. Eliot (London: Faber and Faber, 1960), 238.

[5] T. S. Eliot, ‘John Dryden’, in Selected Essays , third enlarged edition (London: Faber and Faber, 1951), 309-310, 314. Dryden was also, of course, a translator of genius. ‘If I had to give my vote to our greatest translator it would go to Dryden’: The Oxford Book of Verse in English Translation, chosen and edited by Charles Tomlinson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), xvii.

[6] Ezra Pound, ‘Prefatio Aut Cimicium Tumulus’, in Selected Prose 1909-1965, edited by William Cookson (London: Faber and Faber, 1973), 360; The Spirit of Romance (1910; New York: New Directions, 1968), 156-157.

[7] John Berryman, ‘Wash Far Away’, in The Freedom of the Poet (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976), 367-386.