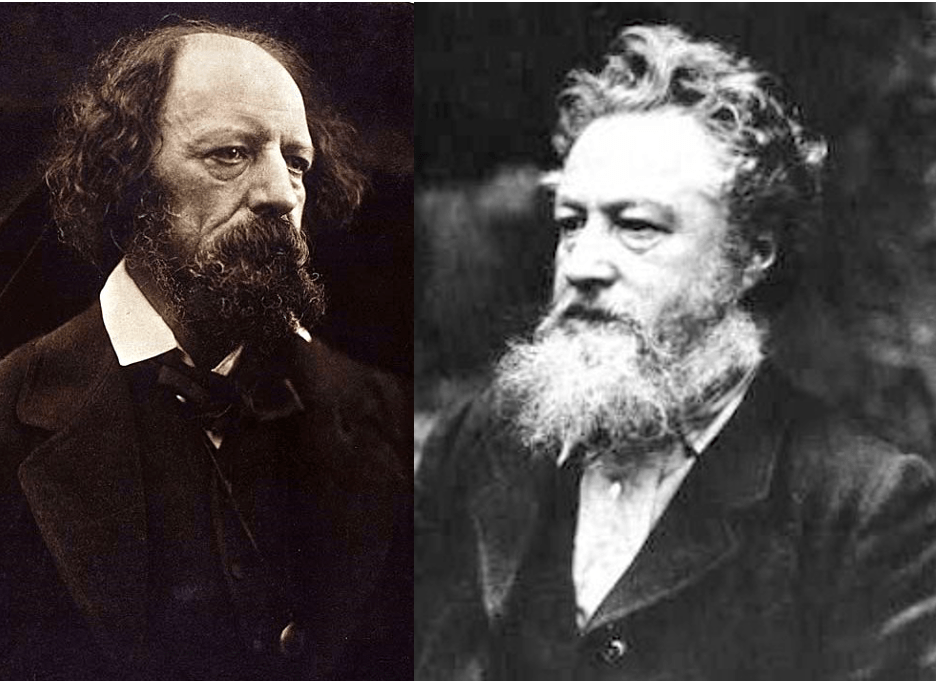

Alfred Lord Tennyson died on 6 October 1892, having served as Queen Victoria’s Poet Laureate for over forty years, the longest ever tenure – though a later octogenarian, John Masefield, came very close. Tennyson’s funeral, which took place six days after his death, was a pretty grand affair. His remains were, the Times reported, ‘consigned to their last resting-place in Poets’ Corner, Westminster’ – the grave of Robert Browning, who had died three years previously, is immediately adjacent to Tennyson’s. All the leading members of the royal family sent representatives (Sir Henry Ponsonby, Sir Dighton Probyn, Lord Edward Cecil) and the place was thronged with bishops, lords and ladies, the pall-bearers including the Duke of Argyll and Lord Kelvin. Conan Doyle, Ellen Terry, John Burns, Frederic Harrison and Henry Irving were among the mourners. In the street outside, vendors were offering, for a penny, copies of the poet’s 1889 lyric, ‘Crossing the Bar’ (author portrait included):

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar,

When I put out to sea,

But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.

Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness of farewell,

When I embark;

For though from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crost the bar.[1]

Tennyson was 80 when he wrote it, so unsurprisingly aware that the encounter with his ‘Pilot’ was not that far off.

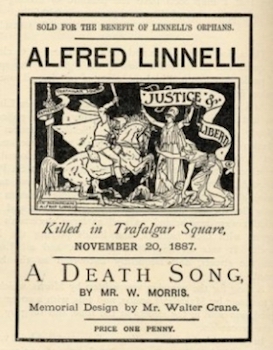

Edward Burne-Jones was particularly excited that the city of Mantua ‘had sent bay from Virgil’s birthplace to lay in the tomb.’ In fact, ‘bay’ and ‘pilot’ occurred in another ‘literary’ interment context a few years later, though William Morris’s ‘country funeral’, Fiona MacCarthy observes, ‘was the absolute antithesis of Tennyson’s burial in Westminster Abbey in 1892.’[2]

(William Morris, Fruit (Wallpaper): William Morris Society: Kelmscott House)

Morris died on 3 October 1896. He was only 62 but such a tireless worker, such a tireless maker, of pictures, poems, translations, tapestries, stained-glass windows, fabrics, carpets, furniture, illuminated books, wallpapers, prose romances and more that, as is often remarked, the primary cause of his death was simply being William Morris. His funeral took place on 6 October, exactly four years after the death of Tennyson. The body had to be transported from Paddington to Lechlade by train (a form of transport that Morris disliked intensely), then taken by cart to Kelmscott Church.

It was a cold wet morning, and the day turned stormy later. In that week’s issue of the Saturday Review (10 October 1896), there were pieces on Morris by George Bernard Shaw, Arthur Symons – and R. B. Cunninghame Graham, whose account of the day on which ‘the most striking figure of our times’ was buried, began with that weather. ‘As we never associated William Morris with fine weather, rather taking him to be a pilot poet lent by the Vikings to steer us from the doldrums in which we now lie all becalmed in smoke to some Valhalla of his own creation beyond the world’s end, it seemed appropriate that on his burial day the rain descended and the wind blew half a gale from the north-west.’ He noted of the arrival at Lechlade: ‘There, unlike Oxford, the whole town was out’, and added that the open haycart on which the coffin was transported to Kelmscott Church was ‘driven by a man who looked coeval with the Saxon Chronicle.’[3]

‘Over the coffin were thrown two pieces of Oriental embroidered brocade, and a wreath of bays was laid at his head’, the Daily News reported. The mourners included, alongside painters, publishers and printers, workmen from Merton Abbey (where the tapestry, weaving and fabric printing workshops were sited), Kelmscott villagers and members of the Art Workers’ Guild, all in their daily working clothes. The architect William Lethaby wrote: ‘It was the only funeral I have ever seen that did not make me ashamed to have to be buried.’[4]

(William Morris, Kelmscott Press Edition of ‘Godefrey of Boloyne’ by William Caxton: William Morris Society: Kelmscott House)

Morris continues to attract enormous biographical and scholarly interest, and warrants it all. So many arts, so many crafts, so many connections, so widespread and generative an influence, cropping up in all manner of places, often the expected ones, sometimes less so. Ezra Pound read Morris to the young Hilda Doolittle, ‘in an orchard under blossoming—yes, they must have been blossoming—apple trees.’ And: ‘It was Ezra who really introduced me to William Morris. He literally shouted “The Gilliflower of Gold” in the orchard. How did it go? Hah! hah! La belle jaune giroflée. And there was “Two Red Roses across the Moon” and “The Defence of Guenevere.”’[5] Pound read Morris to Yeats too, in Stone Cottage at the edge of Ashdown Forest, his translations of the Icelandic sagas.[6] Yeats would later recall of Morris’s prose romances that they were ‘the only books I was ever to read slowly that I might not come too quickly to the end.’[7]

(William Morris, La Belle Iseult: Tate)

Fiona MacCarthy remarks that ‘There was a neurotic basis to his fluency. On a good day he could write 1,000 lines of verse’, and some readers will find some of the longer poems soporific.[8] Penelope Fitzgerald wrote that the lyrics, in her opinion were ‘far the most important part’ of his poetry and, ‘If I could keep them I would cheerfully sweep all the sagas and Earthly Paradises under the carpet.’[9] Other readers, in Morris’s own time, and since, have felt quite differently. Yeats continued to be one of them. In October 1933, he reported to his old friend (and ex-lover) Olivia Shakespear (Pound’s mother-in-law) his attempt to read Morris’s long poem The Story of Sigurd the Volsung to his daughter and then to his wife: ‘and last night when I came to the description of the birth of Sigurd and that wonderful first nursing of the child, I could hardly read for my tears. Then when Anne had gone to bed I tried to read it to George and it was just the same.’[10]

This is probably the passage he refers to, early in Book II:

Then she held him a little season on her weary and happy breast

And she told him of Sigmund and Volsung and the best sprung forth from the best:

She spake to the new-born baby as one who might understand,

And told him of Sigmund’s battle, and the dead by the sea-flood’s strand,

And of all the wars passed over, and the light with darkness blent.

So she spake, and the sun rose higher, and her speech at last was spent,

And she gave him back to the women to bear forth to the people’s kings,

That they too may rejoice in her glory and her day of happy things.[11]

For other admirers of Morris, it may be the campaigner, the Socialist, or perhaps the designer and producer of stained-glass, fabrics, stories, the late romances, the lectures and the essays:

‘To give people pleasure in the things they must perforce use, that is one great office of decoration; to give people pleasure in the things they must perforce make. That is the other use of it.’

‘Does not our subject look important enough now? I say that without those arts, our rest would be vacant and uninteresting, our labour mere endurance, mere wearing away of body and mind.’[12]

Yes, the allusions to damaging and artificial divisions are often wonderfully suggestive of other divisions causing much wider harms – as, of course, they continue to do. And, though I may be prejudiced in this regard, I like his idea, in ‘The Beauty of Life’, of ‘the fittings necessary to the sitting-room of a healthy person’. The first of these is ‘a book-case with a great many books in it’. Oddly, he never seems to mention, let alone recommend, piles of books everywhere else. . .

Notes

[1] Tennyson: A Selected Edition, edited by Christopher Ricks (Harlow: Longman Group, 1989), 665-666.

[2] Fiona MacCarthy, William Morris: A Life for Our Time (London: Faber & Faber, 1994), 631, 673-675.

[3] R. B. Cunninghame Graham, ‘With the North-West Wind’, Saturday Review (10 October 1896), Vol. 82, Issue 2137, 389-390.

[4] Quoted by Philip Henderson, William Morris: His Life, Work and Friends (Harmondsworth: Pelican Books, 1973), 429.

[5] H. D., End to Torment: A Memoir of Ezra Pound, edited by Norman Holmes Pearson and Michael King (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1980), 22-23.

[6] James Longenbach, Stone Cottage: Pound, Yeats and Modernism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 142-143.

[7] W. B. Yeats, ‘The Trembling of the Veil [1922]: Four Years’, in Autobiographies (London: Macmillan, 1955), 141.

[8] MacCarthy, William Morris, ix.

[9] Penelope Fitzgerald to Dorothy Coles, 5 June [1992], So I Have Thought of You: The Letters of Penelope Fitzgerald, edited by Terence Dooley (London: Fourth Estate, 2008), 460.

[10] The Letters of W. B. Yeats, edited by Allan Wade (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1954), 816.

[11] William Morris, The story of Sigurd the Volsung and the fall of the Niblungs (London: Ellis & White, 1877), 80-81.

[12] ‘The Lesser Arts’, in William Morris: The Selected Writings, edited by G. D. H. Cole (London: The Nonesuch Press, 1934), 496.