(Rembrandt van Rijn, Saskia van Uylenburgh in Arcadian Costume: National Gallery, London)

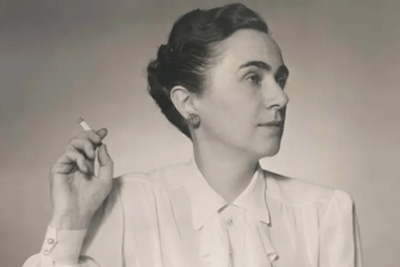

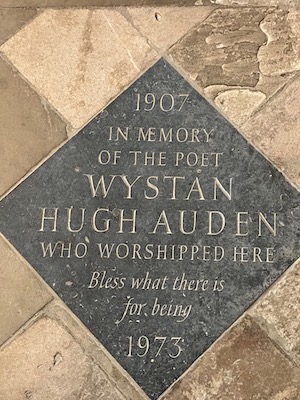

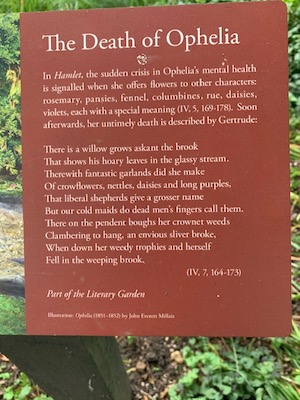

In the other park, which we traverse quite often, there are rosemary bushes to be discreetly ransacked – for potatoes, fish, meat, as well as for remembrance. ‘“There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance”’, Ophelia says. And Laura Cumming notes that when Rembrandt’s wife Saskia van Uylenburgh died in 1642, at the age of 29 and after less than eight years of their marriage, Rembrandt ‘put a sprig of rosemary in her hand: rosemary for remembrance.’[1]

The weather forecast offers a 70% chance of rain. I add an umbrella to my tote bag and am soon walking uphill – in warm sunshine. Yes, the forecasts are more sophisticated these days, with many technical advances – on the other hand, I seem to remember that, in the days before we broke the weather, things were a bit more definite. Or did conditions appear to change every ten minutes then as well?

Under an abruptly darkening sky, I enter the park and the uncertain terrain of rosemary-picking. Plants in a public park: it would never occur to me to pick flowers in one and take them home since they’re for everybody to look at and enjoy. But a bush, herbs, green, largely unnoticed, simply wasted if not used. . . the case is altered, surely. Nevertheless, I aim for discretion and scan the park. Two women with dogs on the grassy slope; a woman with a child in a pushchair walking towards me on the path. Progress is arrested by the sight of a jay, landing on a nearby wooden post. It lingers for ten, fifteen seconds. I stand and stare. Eventually, it moves, I move. The woman says, in passing: ‘Pretty birds, aren’t they?’ Always the loquacious Englishman, I say ‘Yes, very’, moving on to stock up on rosemary and continue my walk into a sunshine resuming its humorous campaign.

In another campaign, the fallout from the presidential debate in Philadelphia on Tuesday night was still dominating the media, and I could still amuse the Librarian by abruptly announcing: ‘They’re eating the dogs!’ but the joke, if that’s what it is, is a dark one. Like a great many other people – at least I hope so, I’m baffled by this stuff much of the time, by those ‘undecided voters’, let alone those determined to make America hate again.

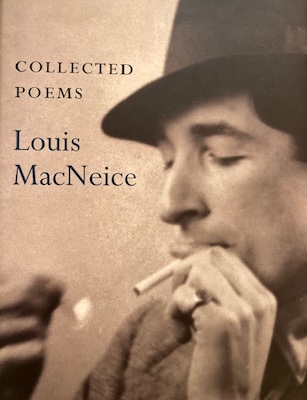

I realised later that it was the birthday of Louis MacNeice, a fine poet who also kept a wary eye on the political weather and who died at the absurdly young age of 55. Thinking of how the wrong things keep happening and the wrong people ending up on top almost invariably, and how far, how much, if at all, the rest of us can be said to bear responsibility, I noted the lines in his Autumn Journal:

And at this hour of the day it is no good saying

“Take away this cup”;

Having helped to fill it ourselves it is only logic

That now we should drink it up.

Nor can we hide our heads in the sand, the sands have

Filtered away;

Nothing remains but rock at this hour, this zero

Hour of the day.[2]

‘Responsibility’ is a handy word. Delmore Schwartz’s famous short story, ‘In Dreams Begin Responsibilities’, which gave his first volume its title, has the narrator watching, on a movie screen, the time just before the beginning of his own life, his parents moving towards their disastrous marriage, which will have a lasting and damaging effect on the poet. He’s ejected from the cinema after shouting at the screen—’“What are they doing?”’—and wakes up ‘into the bleak winter morning of my twenty-first birthday, the windowsill shining with its lip of snow, and the morning already begun.’[3]

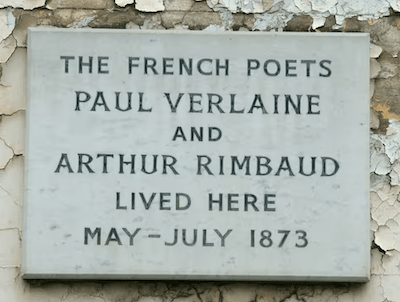

But I was thinking too of the close of Robert Penn Warren’s fine novel, All The King’s Men : ‘soon now we shall go out of the house and go into the convulsion of the world, out of history into history and the awful responsibility of Time.’[4] The connection is with MacNeice, because of that poet’s relationship with Eleanor Clark in 1939-40. When MacNeice was invited by F. R. Higgins to join the Irish Academy of Letters, it was to Eleanor that he wrote about it, saying that ‘The Irish Academy of Letters meets once a year in Dublin’s only decent restaurant and gets so drunk they have to send the waiters away.’[5] Clark grew up in Connecticut, went to Vassar in the 1930s, and worked on their literary magazine with Elizabeth Bishop and Mary McCarthy, among others. She wrote for left-leaning magazines and journals such as The Partisan Review, thought of herself for a while as a ‘Trotskyite sympathizer’ and went to Mexico in the late 1930s. Apparently, she did some translating for Trotsky and was married for a while to his Czech secretary, Jan Frankl. She wrote novels, essays and reviews, children’s books and a memoir, but was probably best-known for her travel books, Rome and a Villa and The Oysters of Locmariaquer. She married Robert Penn Warren in 1952 and died in 1996, aged 82, seven years after Warren himself.

(Eleanor Clark and Robert Penn Warren at their summer home in West Wardsboro, Vermont, 1986: Kentucky Library and Museum)

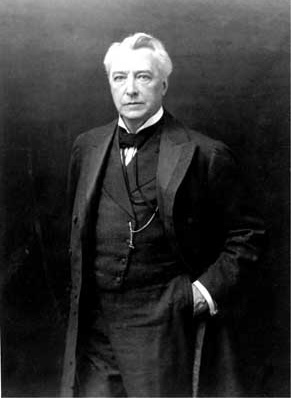

The novelist Nicholas Mosley once wrote that ‘Humans can either learn – or refuse to believe that humans are responsible for themselves.’[6] My favourite use of ‘responsibility’, though, is probably that of the hugely influential Trinidadian radical historian, journalist and political theorist, C. L. R. James, who adopted, in his early years, William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair as the book: ‘By the time I was fourteen I must have read the book over twenty times’. And he adds, a little later: ‘Thackeray, not Marx, bears the heaviest responsibility for me.’[7]

That radical, Thackeray!

Notes

[1] William Shakespeare, Hamlet, IV. v.; Laura Cumming, Thunderclap: A memoir of art and life & sudden death (London: Chatto & Windus, 2023), 61.

[2] Louis MacNeice, Collected Poems, edited by Peter McDonald (London: Faber, 2007), 111.

[3] Ilan Stavans, editor, The Oxford Book of Jewish Short Stories (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 165.

[4] Robert Penn Warren, All The King’s Men (1946; Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2007), 661.

[5] Louis MacNeice, Letters of Louis MacNeice, edited by Jonathan Allison (London: Faber, 2010), 351.

[6] Nicholas Mosley, Efforts at Truth: An Autobiography (London: Minerva , 1996), 299.

[7] C. L. R. James, Beyond a Boundary (1963; London: Vintage, 2019), 24, 52.