An online image of the jacket of the Penguin edition of William Faulkner’s Light in August that I used to own caught my attention. In the background there, E pluribus unum, the one out of many, or many made one. A painful, if not tragic, irony now, in this time of ‘The Breaking of Nations’, as Thomas Hardy wrote in another context—and the phrase with which George Oppen headed his poem ‘The Lighthouses’, for his once close and now estranged friend Louis Zukofsky: ‘(for L. Z. in time of the breaking of nations)’.[1]

So, the one, the one thing, a phrase to dwell upon. ‘The real unum necessarium [the one thing needful] for us’, Matthew Arnold wrote in Culture and Anarchy, ‘is to come to our best at all points.’[2] Emily Dickinson, continuing to resist the extreme pressure at her college to convert and be ‘saved’, in the midst of a religious revival, wrote in a letter of May 1848: ‘I have neglected the one thing needful when all were obtaining it.’[3]

Views on that one needful thing tend to differ, depending on circumstance and character. In Penelope Fitzgerald’s novel Innocence, ‘They were talking about their bowel movements. Loyalty from that quarter was the one thing necessary, said Ricasoli, for absolute peace of mind.’[4] Well, if not the one thing, certainly a contender. And Sarah Bakewell tells us that Montaigne, in his main chamber, had the roof beams painted with classical quotations, including this from Pliny the Elder: Solum certum nihil esse certi / Et homine nihil miseries aut superbius [Only one thing is certain: that nothing is certain / And nothing is more wretched or arrogant than man].[5]

Our best selves; our bowels; uncertainty. In other contexts, that ‘one thing’ is immutability: ‘Strange how, when you are young, you owe no duty to the future; but when you are old, you owe a duty to the past. To the one thing you can’t change.’[6] Or it might be clarity: ‘this book, and my manner of writing it, should make one thing about my life clear: that everything I have lived through either has been completely forgotten or is as yesterday. There is no blue to the horizon of Time.’[7]

Eudora Welty and William Maxwell:

https://www.cleveland.com/books/index.ssf/2011/05/eudora_welty_and_william_maxwe.html

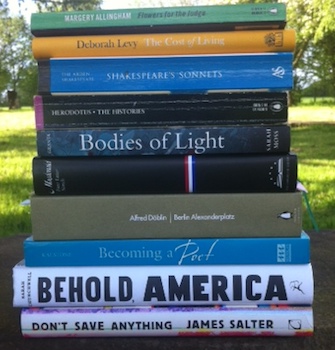

But, it hardly needs saying, one thing tends to lead to another. ‘Ever since Christmas, I have had such an appetite for reading that one thing leads off to another, to the point of madness’, William Maxwell wrote to Eudora Welty.[8] ‘All this really began’, Penelope Fitzgerald wrote to her editor Richard Ollard, ‘when I tried to find out who really discovered the blue poppy, meconopsis baileyi, as it seems not really to have been Colonel Bailey at all, and one thing led to another, but never mind that now.’[9]

‘All this’ was Fitzgerald’s last novel, The Blue Flower, drawing closely on the early life of the German Romantic writer Friedrich von Hardenberg, who took the name ‘Novalis’. His young brother, known as ‘The Bernhard’, reflects on the first chapter of the story that Friedrich has written:

‘He had been struck – before he crammed the story back into Fritz’s book-bag – by one thing in particular: the stranger who had spoken at the dinner table about the Blue Flower had been understood by one person and one only. This person must have been singled out as distinct from all the rest of his family. It was a matter of recognising your own fate and greeting it as familiar when it came.’[10]

The singular, the distinct, the discrete. But the mind moves on, cannot do other than move on. Sebastian Barry wrote in A Long Long Way: ‘Funny how a person thought of one thing and then thought of another thing. And then another thing. And was the third thing brother at all to the first?’[11] A good question. Delano, in Robert Lowell’s play, ‘Benito Cereno’, says:

‘I wish people wouldn’t take me as representative of our country:

America’s one thing, I am another;

we shouldn’t have to bear one another’s burdens.’[12]

In the title story of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s collection, One Thing Leading to Another, Helen Logie accidentally adds snuff instead of curry powder to the dish she serves up to Father Green and his curate, Father Curtin, the two Catholic priests for whom she keeps house. Their lack of response prompts her to a few more culinary experiments, still without getting any reaction. When rheumatism prevents her from pinning up her abundant red hair, its luxuriant looseness is deemed unacceptable. She gets a local lad, Willy Duppy, to help her pin it up but enlisting such aid is also beyond the pale and an impasse is reached. ‘So that was the secret! All a woman need do to get herself attended to was to have a fit of rheumatism that would make it impossible for her to put her hair up.’ Helen moves towards self-assertion and a final exasperated bid for freedom: she gives notice and ultimately reappears in a new guise: ‘soon after Easter, Mr Radbone’s redecorated shop opened its doors for the sale of light refreshments, cooked meats, cakes, jams, scones, and bannocks, and there was Helen presiding over it, assisted by Willy Duppy.’[13]

Temperamentally, I’d say I’m definitely in the one-thing-leading-to-many-others camp; I doubt if I could settle convincingly or consistently on the one thing needful. Perhaps that requires extreme youth; or the kind of certainty that grows increasingly difficult to keep in focus.

References

[1] Thomas Hardy, ‘In Time of “The Breaking of Nations”’, in The Complete Poems, edited by James Gibson (London: Macmillan, 1976), 543; George Oppen, New Collected Poems, edited by Michael Davidson (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2003), 256.

[2] Matthew Arnold, Culture And Anarchy (1869; edited by J. Dover Wilson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), 150.

[3] Quoted by Lyndall Gordon, Lives Like Loaded Guns: Emily Dickinson and Her Family’s Feuds (London: Virago Press, 2011), 43.

[4] Penelope Fitzgerald, Innocence (London: Flamingo, 1987), 148.

[5] Sarah Bakewell, How To Live: A Life of Montaigne in one question and twenty attempts at an answer (London: Vintage 2011), 29.

[6] Julian Barnes, The Only Story (London: Jonathan Cape, 2018), 168.

[7] Richard Wollheim, Germs: A Memoir of Childhood, (London: Black Swan, 2005), 40.

[8] William Maxwell to Eudora Welty, 7 January 1979, Suzanne Marrs, editor, What There Is to Say, We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011), 346.

[9] Letter of 14 September [1994], in So I Have Thought of You: The Letters of Penelope Fitzgerald, edited by Terence Dooley (London: Fourth Estate, 2008), 416.

[10] Penelope Fitzgerald, The Blue Flower (London: Everyman, 2001), 448.

[11] Sebastian Barry, A Long Long Way (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), 124.

[12] Robert Lowell, The Old Glory (London: Faber and Faber, 1966), 149.

[13] Sylvia Townsend Warner, One Thing Leading to Another (London: Chatto and Windus, 1984), 45-63.