(Lawrence Durrell via theamericanreader.com )

When I went to the Ford Madox Ford conference in Swansea in September 2013, I remember thinking, as the train entered Wales, that the change was physically apparent. Could I really look out of a train window and say ‘that’s Wales’? I felt I could but would have been hard put to it if I were challenged to say precisely how and why. But I did, quite abruptly, recall the opening lines of a poem by R. S. Thomas, whose title I could not then remember, and sat leaning against the window, listening to the voice in my head:

To live in Wales is to be conscious

At dusk of the spilled blood

That went into the making of the wild sky,

Dyeing the immaculate rivers

In all their courses.

It is to be aware,

Above the noisy tractor

And hum of the machine

Of strife in the strung woods,

Vibrant with sped arrows.[1]

No, that’s not quite what I heard. The third line had ‘to’ instead of ‘into’, the fourth and fifth lines had vanished from my memory, I had ‘the noise of the tractor’ and ‘the hum’. But not too bad since I hadn’t read the poem for a good thirty years. At home, seeming not to have any R. S. Thomas, I took down from the shelves four or five anthologies of post-1945 poetry, all containing poems by Thomas but not that one. Then I remembered that the hugely important and influential series of Penguin Modern Poets had featured Thomas in the very first volume. I’d owned that, more, at least the first ten volumes in the series, for years. Penguin Modern Poets 10: The Mersey Sound—Roger McGough, Adrian Henri and Brian Patten—was the bestseller, which took everyone by surprise. Where did my copies go? I’m not sure. Perhaps they didn’t go anywhere. It was just me that went. In any case, the Thomas poem, ‘A Welsh Landscape’, yes, was in the initial volume.

(R. S. Thomas via The Telegraph)

It was in April 1962 that Penguin Books launched Penguin Modern Poets. Each volume contained representative selections from three poets and that first volume included, together with Thomas, Elizabeth Jennings – and Lawrence Durrell (born on this day, 27 February 1912, in Jalandhar, India). I don’t know how far the series had gone before I came to it but there was a handful of poems of which I recalled parts, sometimes only a few lines, for years.

The Thomas was one and another, in the same volume, was by Durrell. It was called ‘The Parthenon’, dedicated ‘For T. S. Eliot’, and it was the direct, colloquial beginning that stuck in my head:

Put it more simply: say the city

Swam up here swan-like to the shallows,

Or whiteness from an overflowing jar

Settled into this grassy violet space,

Theorem for three hills,

Went soft with brickdust, clay and whitewash,

On a plastered porch one morning wrote

Human names, think of it, men became the roads.[2]

Looking at it now, of course, I’m struck by more details: the conversational opening phrase followed by the word ‘say’; the artful sibilants, ‘swam’ to ‘swan’ then, with the modifying ‘like’, shifting to ‘shallows’. The word ‘jar’ in a grassy space would prompt me to look back at Keats’s ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ via Wallace Stevens, whose ‘Anecdote of the Jar’ begins:

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.[3]

This is purely because of the strong recollection of one of my lecturers—surely John Reid?—reading the Stevens poem and looking encouragingly out at his audience: ‘What does that remind you of? What’s Stevens doing there?’ Pause. Then, with a kind of resonant despair: ‘It’s Keats! The urn!’ Packed rows of blank faces gave back whatever was the equivalent then of ‘Yeah, whatever’.

Durrell’s insertion of the word ‘Theorem’ is a nice touch too. He refers often to scientific or mathematical matters, a continuum or simultaneity here, a Freudian slap there, his range of interests always extended beyond the narrowly ‘artistic’. Firmly established in Sommières, he played with the ideas of opposing characteristics of North and South, discerning in France’s great figures ‘a pattern of talents: for scientists, philosophers and thinkers tend to be of northern stock, while the poets, artists and men of action come from the Mediterranean southern fringes.’[4] From Corfu in the mid-1930s, he wrote to his friend Alan Thomas, ‘What do you read when you spend a wet Monday alone? Myself I read one of the sciences.’ But he slyly added: ‘The most exact one to date is demonology. It is fun to follow the growth of science out of magic and demonology, and see it declining again in our time back to magic, its parent.’[5]

Whenever I find myself quoting one of those ‘Cypriot Greek proverbs’ that Durrell used as epigraphs to several chapters in Bitter Lemons, such as ‘A fool throws a stone into the sea and a hundred wise men cannot pull it out’, I’m reminded that, a little further on, he casually notes that, ‘No Greek can resist aphorism; its form will make him believe it to be true, even if it is false.’[6]

A bit more R. S. Thomas followed that early reading of the poems—and a lot more Durrell. The novels, the travel books, essays, letters; plus the connected stuff, the related writers, the sacred places. Greece, Alexandria, Provence. Miller, Cavafy, Seferis, Anaïs Nin. And, of course, the stimulus of conversation, a decade and a half in the office with my friend Andrew, a thoroughgoing Durrellian.

(‘Darling Anaïs, I do feel for you in your cutoffness, and there seems nothing to say to you that will make you less conscious of the distance of light and air which lies between us; the war goes bitter and deep in me – it makes everything taste of ash.’—Letter from Durrell in Greece, quoted in The Journals of Anaïs Nin: Volume Three, 15.

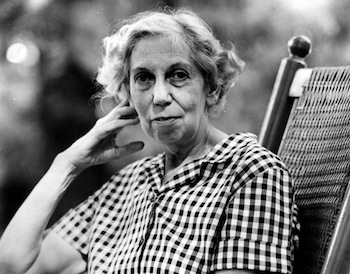

Portrait of Anaïs Nin by the wonderful Brassaï [Gyula Halász, 1899-1984], 1932.)

Durrell was so prolific that, inevitably, some of the writing is a bit hit and miss. But with that range of cultures and countries and curiosities there are plenty of highlights, often cropping up in unexpected places or small-scale pieces or, say, in departures and returns. He writes of April 1941 when, lying ‘on the pitch-dark deck of a caique nosing past Matapan towards Crete’, he thinks back to ‘that green rain upon a white balcony, in the shadow of Albania’, with ‘a regret so luxurious and so deep that it did not stir the emotions at all. Seen through the transforming lens of memory the past seemed so enchanted that even thought would be unworthy of it.’[7] And revisiting Corfu, long afterwards: ‘As for the people . . . Memory does not grow older by a second per thousand years in Greece. Step off the ship and everywhere you will fall upon remembered faces, be instantly recognized and embraced: and I don’t mean only by friends, but by everyone who remembers you in that once, nearly twenty years ago, you gave his son a lesson or let him shine your shoes. Because they remember you they possess you, and you belong to them.’ And then, ‘there is nothing to do but surrender yourself. Strong-willed men break down and cry like babies. No good. The steady flow of hospitality ends only when you are lovingly hospitalized or carried aboard a departing ship on a stretcher.’[8]

Again, rereading The Alexandria Quartet a while back, with that slight nervousness attendant on a revisiting of a past favourite, was as provoking and pleasurable as I hoped it would be. Durrell’s rarely less than diverting, even when he’s being exasperating, a thought that occurred to me when deeply implicated in the more than 1300 pages of The Avignon Quintet, with its maddening hall of mirrors, characters repeatedly dissolving into novelists writing other characters, who are then revealed to be characters in someone else’s novel, while I mutter, ‘Cut it out, Larry’, every ten pages – but read on. ‘There is only trial and error on a journey like this, and no signposts’, as Durrell wrote on another occasion.[9]

Joyeux anniversaire, Larry. Or even, Aürós aniversari.

The International Lawrence Durrell Society site is here: http://www.lawrencedurrell.org/

References

[1] R. S. Thomas, ‘Welsh Landscape’, Collected Poems: 1945-1990 (London: Dent, 1993), 37.

[2] Lawrence Durrell, Collected Poems 1931-1974 (London: Faber and Faber, 1985), 134.

[3] Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems (New York: Vintage Books, 1982), 76.

[4] Lawrence Durrell, Caesar’s Vast Ghost: Aspects of Provence (London: Faber and Faber, 1990), 26.

[5] Alan G. Thomas, editor, Spirit of Place: Mediterranean Writings (1969; London : Faber and Faber, 1988), 47.

[6] Lawrence Durrell, Bitter Lemons (London: Faber and Faber, 1959), 152, 235.

[7] Lawrence Durrell, Prospero’s Cell (1945; London: Faber and Faber, 1962), 133.

[8] Lawrence Durrell, ‘Oil for the Saint: Return to Corfu’, Holiday, Philadelphia, (October 1966), in Spirit of Place, 286, 290.

[9] Lawrence Durrell, The Black Book (1938; London: Faber and Faber, 1977), 233.