(Skylark: https://findingnature.co.uk/animal/skylark/ )

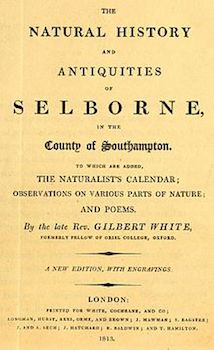

In Great Trade Route, Ford Madox Ford, recalling a visit to a New Jersey truck farm in the company of William Carlos Williams, commented on the behaviour of a snipe which was distracting the men from the nest to protect its young, an example of what Gilbert White famously termed storgé, using the Greek word for familial or ‘natural’ affection, one of the four Greek terms for ‘love’, along with philia, agape and eros: all were discussed in C. S. Lewis’s book, The Four Loves (1960).[1]

Ford often mentioned Gilbert White of Selborne (born 18 July 1720), the ‘parson-naturalist’, in both fictional and non-fictional contexts. In Parade’s End, White crops up in the first volume, Some Do Not. . . as Christopher Tietjens spars with Valentine Wannop on their night-ride.

(Gilbert White)

‘He said:

“Where do you get your absurd Latin nomenclature from? Isn’t it phalæna …”

She had answered:

“From White . . . The Natural History of Selborne is the only natural history I ever read….”

“He’s the last English writer that could write,” said Tietjens.

“He calls the downs ‘those majestic and amusing mountains,’” she said. “Where do you get your dreadful Latin pronunciation from? Phal … i … i … na! To rhyme with Dinah!”

“It’s ‘sublime and amusing mountains,’ not ‘majestic and amusing,’” Tietjens said. “I got my Latin pronunciation, like all public schoolboys of to-day, from the German.”’[2]

Later, in the third volume, A Man Could Stand Up—, Tietjens is in the trenches, where his Sergeant enthusiastically praises the skylark’s ‘Won’erful trust in yumanity! Won’erful hinstinck set in the fethered brest by the Halmighty!’

Tietjens says ‘mildly’ that he thinks the Sergeant has ‘got his natural history wrong. He must divide the males from the females. The females sat on the nest through obstinate attachment to their eggs; the males obstinately soared above the nests in order to pour out abuse at other male skylarks in the vicinity.’

‘“Gilbert White of Selbourne,” he said to the Sergeant, “called the behaviour of the female STORGE: a good word for it.” But, as for trust in humanity, the Sergeant might take it that larks never gave us a thought. We were part of the landscape and if what destroyed their nests whilst they sat on them was a bit of H[igh].E[xplosive]. shell or the coulter of a plough it was all one to them.’

The sergeant is highly sceptical of such sentiments:

‘“Ju ’eer what the orfcer said, Corporal,” the one said to the other. Wottever’ll ’e say next! Skylarks not trust ’uman beens in battles! Cor!”

The other grunted and, mournfully, the voices died out.’

Later in the same volume, Ford recurs to White in Valentine’s own reflections – Ford uses the image or allusion echoed in the thoughts of multiple characters to frequently brilliant effect:

‘Her mother was too cunning for them. With the cunning that makes the mother wild-duck tumble apparently broken-winged just under your feet to decoy you away from her little things. STORGE, Gilbert White calls it!’[3]

(The Wakes, Gilbert White’s house:

http://gilbertwhiteshouse.org.uk/?venue=gilbert-whites-house)

In The Farther Shore: A Natural History of Perception, 1798-1984, a superb, rich study of how technological developments since the eighteenth century have affected the ways in which we interpret the world, Don Gifford wrote of how, for Samuel Johnson and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the ambition to be generally well read, that is, to have a reasonable grasp of all that was being published and made available, ‘was within reach’, and that a community of those sharing that distinction or at least that ambition was ‘at least imagined to be a given among educated men and women.’ His footnote mentions the assumption evident in Gilbert White’s letters that his correspondents shared his acquaintance with Dryden, Pope, Addison, Swift, Gray, Johnson, Hume, Gibbon, Sterne – as well as with the Bible, Virgil, Homer, Horace, the Koran, Chaucer, Shakespeare and Milton. By the mid-80s (when he was writing this book), Gifford adds, ‘the idea of being well read and of belonging to such a community is a joke we have politely learned not to mention except with a shrug of self-deprecation.’

Of course, White’s acquaintance with Pope was not only with the man’s work: he was presented with a copy of Pope’s six-volume translation of the Iliad by the poet himself, when graduating with distinction from Oriel College, Oxford, in 1743.[4]

White’s fascinating and deceptively simple work has embedded itself in English culture in numerous contexts. His genius, as Ronald Blythe remarks, was ‘to revolutionise the study of natural history by noting what exactly lay outside his own back-door.’[5] In his first letter to the Honourable Daines Barrington in June 1769, White wrote, ‘I see you are a gentleman of great candour, and one that will make allowances; especially where the writer professes to be an out-door naturalist, one that takes his observations from the subject itself, and not from the writings of others’ (Selborne 104). He produced hundreds of pages, records of looking and listening and remembering and wondering. Birds, plants, insects, weather, animals, not least the human. ‘My musical friend, at whose house I am now visiting, has tried all the owls that are his near neighbours with a pitch-pipe set at concert-pitch, and finds they all hoot in B flat. He will examine the nightingales next spring’ (Selborne 127).

The local as the universal. A hundred and eighty years after White’s death, William Carlos Williams would note that the poet’s business was ‘to write particularly, as a physician works, upon a patient, in the particular to discover the universal.’ He quoted the line of John Dewey’s that he had come upon by chance, ‘The local is the only universal, upon that all else builds’, commenting elsewhere that, ‘in proportion as a man has bestirred himself to become awake to his own locality he will perceive more and more of what is disclosed and find himself in a position to make the necessary translations.’[6] Williams in Rutherford; Thoreau in Concord; White in Selborne.

Don Gifford points out that, ‘In effect, White’s perspective differs radically from our own because he had no a priori basis for distinguishing between trivial and significant things.’ So, in addition to seeing with his own eyes, White ‘had to see cumulatively, a second order of seeing’. He tells the story of Henry Thoreau reducing Ellery Channing to tears when the two men went out into the woods together: Channing knew so little about what to record that he returned with an empty notebook, desperate and frustrated.[7]

White’s journals were published in 1931 and, Alexandra Harris comments, ‘his work was tirelessly reissued over the next decade.’ But then, in addition to being valued for his ‘timeless qualities’, White was ‘also being used as someone relevant to the present time precisely because the world he knew was disappearing.’[8]

When we read those writers detailing the current decline or disappearance of so much British wildlife, through environmental damage, farming practices and government policies, the parallels hardly need stressing.

On the matter of White’s journals, let your fingers do the running, to this superb resource:

http://naturalhistoryofselborne.com/

House and garden, café and shop?

http://www.gilbertwhiteshouse.org.uk/

References

[1] Ford Madox Ford, Great Trade Route (London: Allen & Unwin, 1937), 184; Gilbert White, The Illustrated History of Selborne (London: Macmillan, 1984), 114, 133-134.

[2] Ford Madox Ford, Some Do Not. . . (1924; edited by Max Saunders, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2010), 163-164.

[3] Ford Madox Ford, A Man Could Stand Up— (1926; edited by Sara Haslam, Manchester: Carcanet, 2011), 63, 64, 65, 201.

[4] Don Gifford, The Farther Shore: A Natural History of Perception (London: Faber and Faber, 1990), 158 and n., 5.

[5] Ronald Blythe, Aftermath: Selected Writings 1960-2010, edited by Peter Tolhurst (Norwich: Black Dog Books, 2010), 226.

[6] William Carlos Williams, The Autobiography of William Carlos Williams (New York: New Directions, 1967), 391; Selected Essays (New York: New Directions, 1969), 28.

[7] Gifford, Farther Shore, 10, 11.

[8] Alexandra Harris, Romantic Moderns: English Writers, Artists and the Imagination from Virginia Woolf to John Piper (London: Thames & Hudson 2010), 171, 173.

.

.