Almost August. Record–breaking temperatures in South Korea and Japan but a dull, grey morning here today. Even the saxophonist who practises in the small wood in the park may postpone his session for a while.

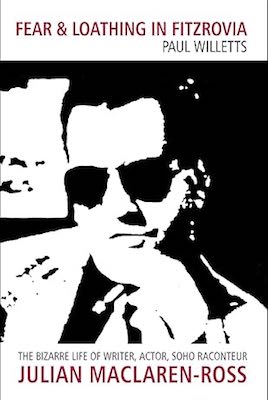

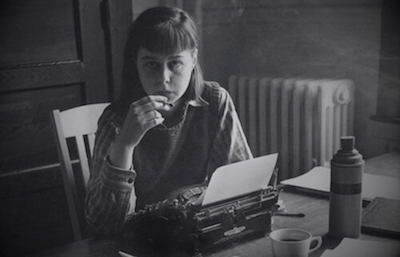

Emerging from Paul Willetts’ biography of Julian Maclaren-Ross, I was a little dizzy from the extraordinary sequences of work done, or proposed, or rewritten, of contracts honoured or let slip, of rooms and suites and flats rented and left in a series of moonlight flits or evictions, of creditors and lawsuits, landladies, hoteliers, retailers (a pram for his son Alex) and the post office (for telephone bills), of separations from, and reconciliations with, wives and girlfriends.[1] It’s difficult not to have a sense of being slightly bruised by contact with the innumerable knocks that the writer underwent. He was incurably extravagant and wasteful with money, nor did the alcoholism, heavy smoking, bad diet, amphetamine use and lack of exercise help much, and the fatal heart attack at the age of fifty-two is not wholly unexpected.

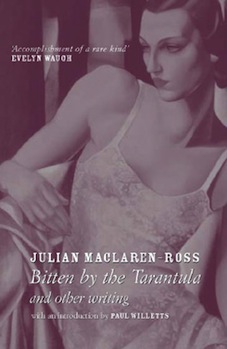

The two undeniable positives, though, are the biography itself, a prodigious feat of research and writing; and Maclaren-Ross’s own staggering fecundity. The novels, short stories, sketches, radio dramas, adaptations, autobiographies, screenplays, parodies, memoirs, reviews and essays emerge at an astonishing rate. Writing often through the night, he seems to turn out entire radio drama series in days, reviews and sketches in hours, year after year through the 1940s, 1950s and into the early 1960s, always in financial distress and increasingly aware that the impact made by some of his early work had not been maintained and had ebbed away. It’s remarkable, given the rate of production and the conditions in which most of it was written, that so much of it is so good. Some of the stories, the novel, Of Love and Hunger, the memoirs, many of the superb parodies and critical writings (on cinema as well as literature) in Bitten By the Tarantula, are assured, often very funny, and hugely impressive.

Endless monologues on a barstool in Fitzrovia. The teddy-bear coat, the sharp suit, the cigarette-holder, the silver-topped malacca cane, the snuff box, the eternal dark glasses: ‘From an early age’, Paul Willetts writes, ‘Julian put as much effort into propagating his personal myth as perfecting his prose style’ (306), going on to mention the many characters in poems and novels that are based on him, as well as the memoirs in which he features. Pubs and clubs, magazines and anthologies, are threaded through the story as much as boxers and bullfighters are in Hemingway’s, and Maclaren-Ross encountered an extraordinary range of writers, editors, publishers, painters and BBC producers. One of these, who became increasingly important in his desperate pursuit of commissions and payments, was Reginald Donald ‘Reggie’ Smith (born on this day, 31 July, 1914), whose name rang a bell because he’d cropped up in a couple of other stories. Married to the novelist Olivia Manning, he’s familiar to readers of her Balkan Trilogy as the model for her central character Guy Pringle (to viewers of the superb adaptation, it is, of course, Kenneth Branagh). Smith crops up on more than thirty pages of Willetts’ biography because he was hugely supportive of Maclaren-Ross for some years. He was a friend of the novelist and critic Walter Allen and of Louis MacNeice, and had been to King Edward Grammar School in Aston, Birmingham, with poet Henry Reed and George D. Painter, future biographer of Marcel Proust. When he married Olivia Manning in August 1939 at Marylebone Registrar’s Office, their witnesses included Stevie Smith and Walter Allen. Their best man had been written into the certificate as ‘Louise MacNeice’—both bride and groom noticed but said nothing—and Olivia seems to have taken the opportunity to shave a few years off her age, her birthdate recorded there as 1911 (in fact it was 1908).[2]

I may briefly take refuge now in something calmer, less harassed—perhaps a Simenon. Not that the world of Inspector Jules Maigret is entirely detached from that of Julian Maclaren-Ross, one of whose many publications was a translation, published by Penguin Books in association with Hamish Hamilton in 1959: Maigret and the Burglar’s Wife. . .

Notes

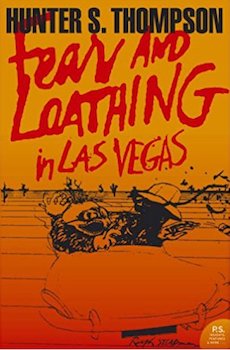

[1] Paul Willetts, Fear & Loathing in Fitzrovia: The Bizarre Life of Writer, Actor, Soho Raconteur Julian Maclaren-Ross, revised edition (London: Dewi Lewis, 2013). Willetts also introduces Collected Memoirs (London: Black Spring Press, 2004) and Bitten By the Tarantula and other writing (London: Black Spring Press, 2005). Penguin Books published Of Love and Hunger, with an introduction by D. J. Taylor, in 2002. ‘The Weeping and the Laughter’ is subtitled ‘A Chapter of Autobiography’ in Collected Memoirs (1-110).

[2] Neville & June Braybrooke, Olivia Manning: A Life (London: Chatto & Windus, 2004), 54, 58, 59.

.

.