(Frederick William Newton Whitehead, A Frosty Morning: Dudley Museums Service)

‘But it must be remembered, that life consists not of a series of illustrious actions, or elegant enjoyments; the greater part of our time passes in compliance with necessities, in the performance of daily duties, in the removal of small inconveniences, in the procurement of petty pleasures; and we are well or ill at ease, as the main stream of life glides on smoothly, or is ruffled by small obstacles and frequent interruption. The true state of every nation is the state of common life.’[1]

I have a new hat, woollen, of the kind so frequently worn by sensible people in cold weather. My hat history is not an inspiring one but in this I look no more ridiculous than other wearers. Perhaps just a little more. Were it a magic hat, it might explore the current rumours of an illegal American invasion of a sovereign, oil-rich country while also analysing the strange sensation of having been here before. But of course there were differences and I’m reminded of the observation by C. L. R. James, ‘To the extent that a historical parallel is suggestive, to that very degree it is dangerous.’

James was writing of interconnections, not only with reference to cricket and colonialism but also cricket and art: ‘We may some day be able to answer Tolstoy’s exasperated and exasperating question: What is art? – but only when we learn to integrate our vision of Walcott on the back foot through the covers with the outstretched arm of the Olympic Apollo.’[2]

(Biography of Sir Clyde Walcott via New Beacon Books)

More broadly still, that two-way flow of influence and attraction that many nationalists and imperialists are unwilling or unable to comprehend. Beyond all manner of boundaries. Ian Baucom, writing of James, referred to his exploration of the false dichotomy of ‘here’ and ‘there’: the assertions of taking ‘Englishness’ abroad tending to forget or elide the ‘un-Englishness’ constantly flowing back into England. England’s history, after all, was and is, inextricably, the history of those others outside England too, the beyond also the within.[3]

I was glad to learn that ‘bounder’, a cad, an ill-bred person, though now long ‘archaic’ once also meant a limit, landmark or boundary. Even amidst the current icy weather, all along the lower half of our road, dead leaves are heaped against the kerbs, the recycling bins and front doorsteps, the park being just a stone’s throw away and a line of London plane trees just beyond its boundary wall.

This border at least is easily crossed, if not always elegantly, and is clearly visible to the naked eye. On Friday 18 November 1870, the Reverend Francis Kilvert wrote in his diary of sitting in Mrs Powell’s cottage in Killey, ‘feeling for the boundary notch in the chimney’, this being somewhere along the wavy line separating England from Wales on the map. A child had been born there that they had been careful to have born in England, ‘in the English corner of the cottage’, the midwife having Betsey deliver the child standing.[4]

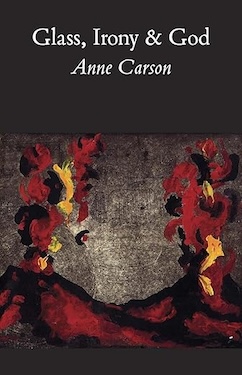

The Finnish word ‘susiraja’ – literally wolf border, the boundary between the capital region and the rest of the country, implying perhaps that everything outside is wilderness – gave Sarah Hall the title of her fine 2015 novel.[5] The poet and translator Anne Carson also touches on boundaries – and wolves: ‘The wolf is a conventional symbol of marginality in Greek poetry. The wolf is an outlaw. He lives beyond the boundary of usefully cultivated and inhabited space marked off as the polis, in that blank no man’s land called to apeiron (“the unbounded”). Women, in the ancient view, share this territory spiritually and metaphorically in virtue of a “natural” female affinity for all that is raw, formless and in need of the civilizing hand of man.’[6]

That civilizing hand seems to have been sawing off its own limbs of late but we should focus on the positives. Hardly a promising start to the new year but there’s plenty of it left. Remembering Thomas Carlyle’s 1829 essay ‘Signs of the Times’, it occurs to me that its most familiar line (for those to whom any line of it is familiar) is probably ‘Men are grown mechanical in head and in heart, as well as in hand.’ But my eye was caught by a couple of other sentences: ‘There is no end to machinery. Even the horse is stripped of his harness, and finds a fleet fire-horse invoked in his stead.’

17 February (in the lunar calendar) marks the beginning of the Chinese New Year; and 2026 is, I gather, the year of the Horse, specifically the Fire Horse. All the commentaries—astrological and others—on this configuration (yang and yang) that occurs every sixty years seem to hint at both opportunity and danger, energy, heat, a greater willingness to take risks, one of them the risk of burn-out. The word ‘expansion’ cropped up once or twice, hardly reassuring in the present global context. Still, best wishes to all for this year, and, as more than one person said in my hearing over Christmas, ‘May the gods be kind.’

Notes

[1] Samuel Johnson, A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland, edited by Ian McGowan (1775; Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 1996), 18-19.

[2] C. L. R. James, Beyond a Boundary (1963; London: Vintage, 2019), 205, 279.

[3] Ian Baucom, Out of Place: Englishness, Empire and the Locations of Identity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), ‘Introduction : Locating English Identity’, 38-39.

[4] Francis Kilvert, Kilvert’s Diary, edited by William Plomer, Three volumes (London: Jonathan Cape, 1938, reissued 1969), Volume 1, 262.

[5] Sarah Hall, The Wolf Border (London: Faber 2015).

[6] Anne Carson, ‘The Gender of Sound’, in Glass, Irony & God, introduction by Guy Davenport (New York: New Directions, 1995), 124.