In an article in Future in 1917, Ezra Pound wrote in praise of Thomas Lovell Beddoes (who died on this day, 26 January, in 1849), ‘Elizabethan’, he argued, ‘that is, if by being “Elizabethan” we mean using an extensive and Elizabethan vocabulary full of odd and spectacular phrases: very often quite fine ones.’[1] (Before and after this date, Ford Madox Ford was arguing – frequently – that Joseph Conrad was ‘Elizabethan’).[2]

Pound owned a two-volume set of Beddoes’ writings (1890) and was obliged to offer thanks to its editor Edmund Gosse, of whom he had rather less than complimentary things to say on other occasions.

Beddoes published relatively little in his lifetime (he committed suicide at the age of forty-five) and it was the posthumously-published Death’s Jest-Book which Pound was focused upon.

‘Tremble not, fear me not

The dead are ever good and innocent,

And love the living.’ (IV, iii, 111-113)[3]

Pound was concerned to ask ‘why so good a poet should have remained so long in obscurity’. Was it largely a matter of chronology, of which poets are still alive and flourishing or lately dead and widely mourned?

‘No more of friendship here: the world is open:

I wish you life and merriment enough

From wealth and wine, and all the dingy glory

Fame doth reward those with, whose love-spurned hearts

Hunger for goblin immortality.

Live long, grow old, and honour crown thy hairs,

When they are pale and frosty as thy heart.

Away. I have no better blessing for thee.’ (I, ii, 291-298)

‘The patter of his fools,’ Pound says, ‘is certainly the best tour de force of its kind since the Elizabethan patter it imitates’:

‘My jests are cracked, my coxcomb fallen, my bauble confiscated, my cap decapitated. Toll the bell; for oh, for oh! Jack Pudding is no more.’ (I, i, 9-11)

Jack Pudding

(The Traditional Tune Archive: http://tunearch.org/wiki/Annotation:Jack_Pudding )

‘I try to set out his beauties without much comment, leaving the reader to judge, for I write of a poet who greatly moved me at eighteen, and for whom my admiration has diminished without disappearing.’

Thirty years later, at Pisa, Pound wrote:

Curious, is it not, that Mr Eliot

has not given more time to Mr Beddoes

(T. L.) prince of morticians

where none can speak his language[4]

That last line remembers Death’s Jest-Book once more (quoted in Pound’s essay):

‘Thou art so silent, lady; and I utter

Shadows of words, like to an ancient ghost,

Arisen out of hoary centuries

Where none can speak his language.’ (I, ii, 141-144)

As to our local connection: Beddoes was born in 1803, at 3 Rodney Place, Clifton, Bristol. His father, the eminent medical man, Dr Thomas Beddoes was married to Anna Edgeworth, sister of the novelist, Maria Edgeworth. Four years before the birth of his son, Dr Beddoes had succeeded in establishing the Pneumatic Institution in Hotwells, Bristol, concerned with treatment through the inhalation of various gases. At Hotwells, the first superintendent was Humphry Davy, whose experimental work included investigation of the properties of nitrous oxide (laughing gas). Alethea Hayter suggests that Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘first real habitation to opium’ may have resulted from a recommendation in Dr Thomas Brown’s Elements of Medicine, edited by none other than Dr Beddoes.[5]

If there were dreams to sell,

What would you buy?

Some cost a passing bell;

Some a light sigh,

That shakes from Life’s fresh crown

Only a roseleaf down.

If there were dreams to sell,

Merry and sad to tell,

And the crier rung the bell,

What would you buy? (Dream-Pedlary, in Poetical Works, I, 46)

The Thomas Lovell Beddoes website is here: http://www.phantomwooer.org/

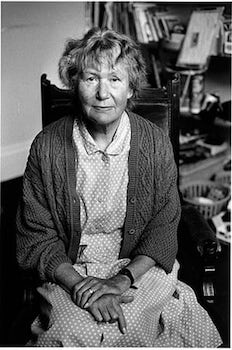

The poet Alan Halsey, who ran the Poetry Bookshop in Hay-on-Wye for nearly twenty years, has written on Beddoes and edited the 2003 edition of the later text of Death’s Jest-Book. He runs West House Books as both publisher and bookseller. His secondhand catalogue has some very choice items indeed:

http://www.westhousebooks.co.uk/

References

[1] ‘Beddoes (and Chronology)’, reprinted (with incorrect publication year of 1913) in Ezra Pound, Selected Prose 1909-1965, edited by William Cookson (London: Faber and Faber, 1973), 348-353. All Pound quotations from this essay.

[2] See ‘Joseph Conrad’, English Review (December 1911), 69, 70; ‘Literary Portraits – XLI. Mr. Richard Curle and “Joseph Conrad”’, Outlook, XXXIII (20 June 1914), 848, 849; Thus to Revisit (London: Chapman & Hall, 1921), 100; ‘Mr Conrad’s Writing’, Literary Supplement to The Spectator, 123 (17 November 1923), in Critical Essays, edited by Max Saunders and Richard Stang (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2002), 230; Joseph Conrad (London: Duckworth, 1924), 18, 25; Letters of Ford Madox Ford, edited by Richard M. Ludwig (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965), 127.

[3] References to Death’s Jest Book in The Poetical Works of Thomas Lovell Beddoes, edited by Gosse (Dent, 1890), Volume II, 5-158.

[4] ‘Canto 80’, The Cantos of Ezra Pound, fourth collected edition (London: Faber and Faber, 1987), 498.

[5] Alethea Hayter, Opium and the Romantic Imagination (London: Faber and Faber, 1971), 27.

.

.