(Archibald Knox, ‘“In preachings of apostles faiths of confessors” (from Knox’s illuminated manuscript “The Deer’s Cry” or “Saint Patrick’s Hymn”’: Manx Museum, Douglas, Isle of Man)

Sitting before the evening news, the Librarian remarks that, if we’d been told ten or fifteen years ago that the world would be like this—the Artic and the Amazon forest on fire, the extreme Right resurgent in Europe again, the widespread mainstream dissemination of racist and supremacist views, this country’s prolonged and painful foundering, the President of the United States in a snit because he couldn’t buy another country and suggesting nuclear strikes to combat hurricanes—we wouldn’t have believed it.

Believe. What a world of a word. ‘I do not believe in Belief’, E. M. Forster wrote in his 1939 essay, ‘What I Believe’. And, ‘Faith, to my mind, is a stiffening process, a sort of mental starch, which ought to be applied as sparingly as possible. I dislike the stuff’.[1] I also own a curious volume called What I Believe, edited by Mark Booth, ‘curious’ not in its contributors (W. H. Auden, Albert Einstein, Jacques Maritain, Rebecca West, Bertrand Russell and, yes, Martin Sheen among them) but in its publishing history, issued in Britain by Firethorn Press, ‘an imprint of Waterstone and Company Limited’, of 193 Kensington High Street, London W8. A Waterstones branch is still at that address, thirty-five years on.

‘The brute necessity of believing something so long as life lasts does not justify any belief in particular’, George Santayana wrote.[2] And Shirley Jackson’s observation seems increasingly pertinent: ‘The question of belief is a curious one, partaking of the wonders of childhood and the blind hopefulness of the very old; in all the world there is not someone who does not believe something. It might be suggested, and not easily disproven that anything, no matter how exotic, can be believed by someone.’[3] These days, of course, that ‘anything’ is believed with greater volume and stridency.

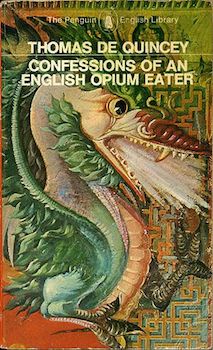

T. S. Eliot famously declared of the essays in For Lancelot Andrewes: Essays on Style and Order, that: ‘The general point of view may be described as classicist in literature, royalist in politics, and anglo-catholic in religion.’[4] The previous year, he had published ‘A Note on Poetry and Belief’, responding to an essay by I. A. Richards: ‘But I cannot see that poetry can ever be separated from something which I should call belief, and to which I cannot see any reason for refusing the name of belief, unless we are to reshuffle names altogether.’[5] Responding to Eliot’s musing about what his friend ‘believed’, Ezra Pound recommended reading Confucius and Ovid, but advanced a few years later to a more precise statement: ‘I believe the Ta Hio.’[6] This—The Great Learning—became, some years later, Ta Hsio: The Great Digest, its most often quoted lines (certainly by me) perhaps: ‘Things have roots and branches; affairs have scopes and beginnings. To know what precedes and what follows, is nearly as good as having a head and feet.’[7]

Certain beliefs—and I pause on the ironic savour of the word ‘certain’ in this context—are, or have been, pretty well obligatory. Northrop Frye writes that: ‘The Christian mythology of the Middle Ages and later was a closed mythology, that is, a structure of belief, imposed by compulsion on everyone. As a structure of belief, the primary means of understanding it was rational and conceptual, and no poet, outside the Bible, was accorded the kind of authority that was given to the theologian. Romanticism, besides being a new mythology, also marks the beginning of an “open” attitude to mythology on the part of society, making mythology a structure of imagination, out of which beliefs come, rather than directly one of compulsory belief.’[8]

I recall, quite specifically, the moment in which I ceased to be a Christian believer, though I may not have then become a Romantic. It was a bright, dry Sunday morning in a village a few miles from Bath. I boarded at a nearby college, though continuing to attend school in the city and, every Sunday morning, the boarders were ferried by the college’s ramshackle coach to the village church. While I stood on the side of the hot road, that belief fell off me like a solid object, as though I’d dropped a stone or a coin, one I wouldn’t bend to pick up again.

‘Lord, I believe’, the father cries out in St Mark’s Gospel, ‘help thou mine unbelief’ (Mark 9: 24).

(Jacopo Palma il giovane, Saint Mark: Hatton Gallery)

Anne Carson writes:

‘Where does unbelief begin?

When I was young

there were degrees of certainty.

I could say, Yes I know that I have two hands.

Then one day I awakened on a planet of people whose hands

occasionally disappear—’[9]

Religious belief clearly doesn’t require buildings and clerical collars. In Of Human Bondage, Somerset Maugham’s Norah tells Philip that she doesn’t believe in ‘churches and parsons and all that’ – but, she adds, ‘I believe in God, and I don’t believe He minds much about what you do as long as you keep your end up and help a lame dog over a stile when you can.’[10] There are, too, very individual manifestations of God. ‘Binding up these sheaves of oats’, Ronald Duncan wrote in his record of wartime smallholding, ‘I am certain I believe in oats. The stalks falling behind the cutter which we draw behind an old car, the monk binding methodically, the new members binding enthusiastically, women with coloured scarves round their heads are gleaning and one cannot glean ungracefully. If one cannot see God in an oatfield one will never see. For, here is the whole of it.’[11]

(Samuel Palmer, The Gleaning Field: Tate)

Kate Atkinson writes of Jackson Brodie in her recent novel: ‘He didn’t let the fact that he was brought up as a Catholic interfere with his beliefs.’[12] Beliefs or faith? In what I suspect has now become my favourite Penelope Fitzgerald novel, she writes of the feast of St Modestus, patron saint of printing, and the blessing of the ikons by the parish priest. ‘Because I don’t believe in this, Frank thought, that doesn’t mean it’s not true.’ Then: ‘Perhaps, Frank thought, I have faith, even if I have no beliefs.’[13]

As to the secular world, who can say? Faith in facts, in political systems, in international law, in human rights? Belief seems sometimes rampant, sometimes inert, stunned, left for dead. It’s a long time since Proust wrote: ‘Facts do not find their way into the world in which our beliefs reside; they did not produce our beliefs; they do not destroy them; they may inflict on them the most constant refutations without weakening them.’[14] Remembering the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, now more than forty years ago, Lavinia Greenlaw asserted that ‘England was no longer England, at least not the England it persisted in believing itself to be.’[15]

And now? Here we are. There they are. So I turn to the Librarian and say yes, I believe you’re right.

Notes

[1] E. M. Forster, Two Cheers for Democracy (London: Edward Arnold, 1951), 77.

[2] W. H. Auden and Louis Kronenberger, The Faber Book of Aphorisms: A Personal Selection (London: Faber and Faber, 1964), 334.

[3] Shirley Jackson, The Sundial (1958; London: Penguin, 2015), 33.

[4] T. S. Eliot, ‘Preface’, For Lancelot Andrewes: Essays on Style and Order (London: Faber and Gwyer, 1928), ix.

[5] T. S. Eliot, ‘A Note on Poetry and Belief’, The Enemy, 1 (January 1927) 15-17.

[6] Ezra Pound, ‘Credo’ (1930) in Selected Prose 1909-1965, edited by William Cookson (London: Faber and Faber, 1973), 53; ‘Date Line’ (1934) in Literary Essays of Ezra Pound, edited by T. S. Eliot (London: Faber and Faber, 1960), 86.

[7] Ezra Pound, Confucius. The Unwobbling Pivot; The Great Digest; The Analects (New York: New Directions, 1969), 29.

[8] Northrop Frye, A Study of English Romanticism (Brighton: The Harvester Press, 1983), 16

[9] Anne Carson, ‘The Glass Essay’ in Glass, Irony & God (New York: New Directions, 1995), 31.

[10] Somerset Maugham, Of Human Bondage (1915; Penguin Books, 1963), 318. Readers of Ford Madox Ford nod sagely at this point—‘I remember my grandfather laying down a rule of life for me. He said: “ Fordie, never refuse to help a lame dog over a stile.”’ See Ancient Lights and Certain New Reflections (London: Chapman and Hall, 1911), 197.

[11] Ronald Duncan, Journal of a Husbandman (London: Faber 1944), 52-53.

[12] Kate Atkinson, Big Sky (London: Transworld, 2019), 10.

[13] Penelope Fitzgerald, The Beginning of Spring (London: Everyman, 2003), 378.

[14] Marcel Proust, The Way by Swann’s, translated by Lydia Davis (London: Allen Lane, 2002), 149.

[15] Lavinia Greenlaw, The Importance of Music to Girls (London: Faber & Faber, 2017), 114.