(John Constable, The Cottage in a Cornfield: V & A)

(To outrun the constable: to go too fast or too far—Eric Partridge, A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English)

What might we have recourse to, after a week of prime ministerial rabble-rousing and incitement to violence and the continued, programmatic fracturing of a nation? Le vin, ça va sans dire—or a visit to Bristol Old Vic, to see six talented women play twenty-one roles in Pride and Prejudice* (Sort of)*, at which I laughed like a lunatic—perhaps even a slightly morose thinking about Englishness—‘“Englishness”, however, is a term that has no fixed meaning but is instead made and re-made in and through history’.[1]

I was browsing through art books and looking at the pictures of John Constable. The combative Geoffrey Grigson once asserted that Constable ‘remains the artist the English have most reason to be proud of and thankful for, without reservation.’[2]

Constable, in his quietly revolutionary way, painted what was in front of his eyes, usually in localities that he knew intimately and loved greatly. And the local, to a greater or larger extent, containing the universal is a familiar enough theme, from Gilbert White through Thomas Hardy to William Faulkner and William Carlos Williams.

‘How much I wish I had been with you on your fishing excursion in the New Forest!’ Constable wrote in 1831 to his close friend, John Fisher. ‘What river can it be? But the sound of water escaping from mill-dams, etc., willows, old rotten planks, slimy posts, and brickwork, I love such things. Shakespeare could make everything poetical; he tells us of poor Tom’s haunts among “sheep cotes and mills” [King Lear]. As long as I do paint, I shall never cease to paint such places. They have always been my delight [ . . . ] Still, I should paint my own places best; painting is with me but another word for feeling, and I associate “my careless boyhood” with all that lies on the banks of the Stour’.[3]

Born in the village of East Bergholt, on the River Stour in Suffolk, son of a prosperous corn merchant, who owned Flatford Mill in East Bergholt and, later, Dedham Mill, Constable painted many pictures of East Bergholt and of Dedham Vale, pictures too of mills, clouds, cottages, cornfields, Hampstead, Brighton, Salisbury Cathedral, and even clouds above cottages in cornfields. He was a great student of clouds.

(John Constable, Seascape Study with Raincloud: Royal Academy of Arts)

During his lifetime, Constable had no great success, not, at least, with an English audience. As late as the last decade of his life, he wrote to his future biographer: ‘Varley, the astrologer, has just called on me, and I have bought a little drawing of him. He told me how to “do landscape,” and was so kind as to point out all my defects. The price of the drawing was “a guinea and a half to a gentleman, and a guinea only to an artist,” but I insisted on his taking the larger sum, as he had clearly proved to me that I was no artist’.[4] Still, though unsold at the 1821 Royal Academy show, The Hay Wain (shown together with View on the Stour Near Dedham and one of Constable’s views of Yarmouth Jetty) was awarded a gold medal at the Paris Salon of 1824, presented by Charles X. The Hay Wain hugely impressed Théodore Géricault and influenced Eugène Delacroix.[5] Originally called Landscape: Noon and produced over a relatively short space of time to meet an exhibition deadline, it has permeated the national consciousness to the extent that a 2005 BBC poll to determine the most popular painting in any British gallery placed it second behind Turner’s Fighting Temeraire.

Constable has certainly suffered more than most from over-familiarity with what are regarded in his work as a quintessential Englishness and scenes of a timeless and untroubled rural world. Peter Kennard’s famous Hay Wain with Cruise Missiles (Chromolithograph and photographs on paper, 1980: Tate) derived much of its power from precisely those perceived qualities. Inevitably, such popularity had its negative effects. In ‘Going to the Pictures’, Alan Bennett remembered that, ‘Besides the Dutch landscapes, which I was exposed to too young, there were other casualties of inept or promiscuous reproduction. I don’t like The Hay Wain because it featured on a table mat at home.’[6]

(John Constable, The Hay Wain: National Gallery)

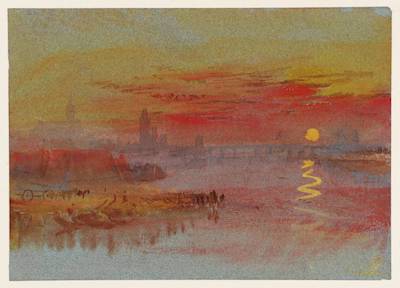

‘The first time I met him was in the year 1844 at the Academy on one of the varnishing days. I am enabled to fix the date because of the picture he exhibited that year, which was that entitled “Rain, Steam and Speed.” I watched him working on this picture. He used rather short brushes, a very messy palette, and, standing very close up to the canvas, appeared to paint with his eyes and nose as well as his hand. Of course he repeatedly walked back to study the effect. Turner must, I think, have been fond of boys, for he did not seem to mind my looking on at him; on the contrary, he talked to me every now and then, and pointed out the little hare running for its life in front of the locomotive on the viaduct. This hare, and not the train, I have no doubt he intended to represent the “Speed” of his title; the word must have been in his mind when he was painting the hare, for close to it, on the plain below the viaduct, he introduced the figure of a man ploughing, “Speed the plough” (the name of an old country dance) probably passing through his brain.’[7]

(J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed: National Gallery)

This is George Dunlop Leslie, RA, genre painter and illustrator—son of Constable’s biographer Charles Robert Leslie—nine years old at the time of which he writes. In fact, the National Gallery website notes that: ‘Turner lightly brushed in a hare roughly midway along the rail track to represent the speed of the natural world in contrast to the mechanised speed of the engine. The animal is now invisible as the paint has become transparent with age, but it can be seen in an 1859 engraving of the painting.’

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/joseph-mallord-william-turner-rain-steam-and-speed-the-great-western-railway

Turner and Constable. Writing to Harman Grisewood in 1972, the poet and artist David Jones wrote of a chance acquaintance that ‘his cut of suit suggested the turf—but then so did that of Sickert, which did not prevent him from being the best English painter since Turner (in my view).’ Still, eleven years earlier, Jones had remembered: ‘I was encamped very near Stonehenge early in the First War, before going to France, and must confess to not finding it very impressive. I like Constable’s picture of it, though.’[8]

(John Constable, Stonehenge: Victoria and Albert Museum)

‘I have made a beautiful drawing of Stonehenge’, John Constable wrote to Leslie in September 1836, and made several other studies before producing the watercolour now in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection. ‘He always kept the influence of earlier masters on his own work under close control’, Raymond Lister writes, ‘and though Stonehenge, for instance, contains a suggestion of Meindert Hobbema in the plein air rendering, it remains Constable’s conception and could not have been painted by any other artist.’[9]

It was, apparently, in 1819—the birth year of Turner’s great champion, John Ruskin—that a critic first compared Constable’s painting with Turner and, ‘again for the first time a critic attempted to liken Constable’s painting with the great tradition of rustic landscape associated with Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema.’[10]

Hobbema: painter of trees, mills, woods and cottages. Constable was not uncritical of him but, replying to Fisher’s advice to ‘diversify your subject this year as to time of day’—‘People get tired of mutton at top, mutton at bottom, and mutton at the side, though the best flavour and smallest size’—he wrote that he himself didn’t enter into ‘that notion of varying one’s plans to keep the public in good humour.’ He went on: ‘Change of weather and effect will always afford variety. What if Vander Velde had quitted his sea pieces, or Ruysdael his waterfalls, or Hobbema his native woods. The world would have lost so many features in art’ (Leslie 131). Half a century after Constable’s death, Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo, then in London:

‘Now I for my part have always remembered some English pictures such as “Chill October” by Millais and, for instance, the drawings by Fred. Walker and Pinwell. Just notice the Hobbema in the National Gallery; you must not forget a few very beautiful Constables there, including “Cornfield,” nor that other one in South Kensington called “Valley Farm.”’[11]

(John Constable, Valley Farm: Tate)

Unfortunately for Constable, Ruskin, who became the most influential art critic in the country, was consistently highly critical of him, claiming that he could not draw and was not accurate or specific enough in rendering the details of the natural world. A major factor in this evaluation was that he was combatting the great claims made by C. R. Leslie who, by setting Constable higher than Turner, prompted Ruskinian counter-attacks.

‘Unteachableness seems to have been a main feature of his character, and there is corresponding want of veneration in the way he approaches nature herself’, Ruskin asserted. Having found no signs of Constable ‘being able to draw’, this resulted in ‘even the most necessary details’ being ‘painted by him inefficiently.’ Then: ‘His works are also eminently wanting both in rest and refinement: and Fuseli’s jesting compliment[12] is too true for the showery weather, in which the artist delights, misses alike the majesty of storm and the loveliness of calm weather; it is great-coat weather, and nothing more. There is strange want of depth in the mind which has no pleasure in sunbeams but when piercing painfully through clouds, nor in foliage but when shaken by the wind, nor in light itself but when flickering, glistening, restless and feeble. Yet, with all these deductions, his works are to be deeply respected, as thoroughly original, thoroughly honest, free from affectation, manly in manner, frequently successful in cool colour, and realizing certain motives of English scenery with perhaps as much affection as such scenery, unless when regarded through media of feeling derived from higher sources, is calculated to inspire.’[13]

That ‘want of veneration’ and ‘feeling derived from higher sources’ hint at some of the criteria Ruskin was applying – though he would suffer a temporary loss of faith in the next decade, at this stage the recognition and appreciation of beauty was inseparable—and indispensable—in his eyes from the worship of God. Constable was not reverent enough and his painting did not explicitly transfigure. ‘The great vice of the present day is bravura, an attempt to do something beyond the truth’, he wrote to John Dunthorne (Leslie 15) and that ‘truth’ remained his concern, even if this makes his pictures seem undramatic to his audience, too easy at first glance to interpret and digest, We might occasionally wonder ‘where is it?’ when looking at a Constable landscape – but rarely ‘what is it?’ as prompted by some Turner canvases and sketches. There is surely room for both: the viewer, after all, moves through different ages, moods, states of mind, of knowledge, of experience, of taste. We should be able to manage Turner, Constable – and John Ruskin too.

Notes

[1] Frances Spalding, John Piper, Myfanwy Piper: Lives in Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 189.

[2] Geoffrey Grigson, Britain Observed: The Landscape Through Artists’ Eyes (London: Phaidon Press, 1975), 93.

[3] Constable to Archdeacon John Fisher, 23 October 1831: C. R. Leslie, Memoirs of the Life of John Constable: Composed Chiefly of His Letters (1845; edited by Jonathan Mayne, London: Phaidon Press, 1951), 85-86.

[4] Leslie, Memoirs of the Life of John Constable, 194.

[5] Constable: The Great Landscapes, edited by Anne Lyles (London: Tate Publishing, 2006), 140, 142.

[6] Alan Bennett, Untold Stories (London: Faber and Faber and Profile Books, 2005), 463.

[7] G. D. Leslie, The Inner Life of the Royal Academy (London: John Murray, 1914), 144-145.

[8] Letter to Juliet and Richard Shirley Smith, 17 August 1961: Anthony Hyne, David Jones: A Fusilier at the Front (Bridgend: Seren, 1995), 30.

[9] Raymond Lister, British Romantic Painting (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), Plate 37.

[10] Anne Lyles, ‘Soliciting Attention: Constable, the Royal Academy and the Critics’, in Constable: The Great Landscapes, 36.

[11] The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, second edition, three volumes (London: Thames & Hudson, 1978), II, 300.

[12] ‘Speaking of me, he says, “I like de landscapes of Constable; he is always picturesque, of a fine colour, and de lights always in de right places; but he makes me call for my greatcoat and umbrella.”’ Constable, letter of 9 May 1823: Leslie, 101.

[13] John Ruskin, Modern Painters, Volume 1, edited by E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (London: George Allen, 1903), 191.