(Natalia Ginzburg via the TLS)

Recently, reading a novella by Natalia Ginzburg, I came across this passage, a memory of Carmine Donati, an architect, forty years old.

‘He remembered one occasion when he was very tiny, still in his mother’s arms, and they were in town, at the station. It was night time and pouring with rain. There were crowds of people with umbrellas waiting for the train, and mud was running between the tracks. Why on earth his memory should have squandered and destroyed so many events, and yet preserved that moment so accurately, bringing it safely through the years, tempests and ruins, he did not know. At that point, he could not remember anything about himself, what clothes and shoes he had worn, what wonder and curiosity had woven and unwoven itself in his thoughts at the time. His memory had thrown all that out as useless. Instead, he had retained a whole pile of random detailed impressions, that were hazy, but light as a feather. He had kept the memory of voices, mud, umbrellas, people, the night.’[1]

(Rohan Kanhai, via The Cricket Monthly)

Memory, the eternal object of fascination, certainly for a reader of Ford Madox Ford and an occasional, though rather short-winded, visitor to the Marcel Proust estate. Why, years after I stopped following test cricket (and reading Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack) could I recall the exact scores made by the Guyanese batsman Rohan Kanhai in Adelaide in 1960-61? Or the first paragraph of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, not having read it for forty years? Or the exact shape and feel of the gates of our house in Gillingham, Kent, when I was two or three years old? All these against the important—sometimes crucial—information that fell out of my head the moment it arrived there. Arbitrary, unreliable, disordered, beloved memory.

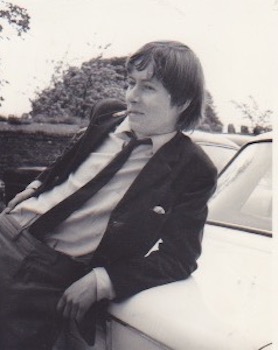

Up in the loft, surrounded by books—as I would be practically anywhere else in the house save for the bathroom—and distracted by misreading the maker’s name on the iron as ‘Russell Hoban’ (literary tunnel vision) as I attempt to subdue a clean shirt, I catch sight of an old photograph of myself, unearthed by the Librarian in her recent excavations, clearing and culling.

I have a few other photographs of similar vintage but buried in boxes or an old album given to me by my mother and misplaced since, of course. This recent rediscovery would probably prompt remarks similar to those elicited by others of its kind. ‘Nice-looking chap. What happened?’ To which the standard rejoinder is: ‘Life’.

Bad haircut; cigarette hanging out of mouth; good grief, thin tie tucked into trousers. I was, I think, working at a garage at the time: it was primarily a Fiat dealership but also sold used cars, specialising in Rovers. I was the accounting troubleshooter, brought in because not all the mechanics’ hours were being charged and I was to track them down. The owner—father of a close friend, who also worked there as a salesman—paid for my driving lessons until I passed my test and became more generally useful, able occasionally to collect and deliver new cars when I wasn’t hunched over an adding-machine, telling bad jokes to the foreman or flirting with the forecourt attendant.

Such recollections seem stable enough—are they also static, black and white, like my photographs of the time, because of my photographs of the time? ‘Like history, memory is inherently revisionist and never more chameleon than when it appears to stay the same.’[2] The novelist Patrick White wrote that, ‘although memory is the glacier in which the past is preserved, memory is also licensed to improve on life.’[3]

Photographs of oneself. I’m reminded of Marie Darrieussecq’s discussion of Paula Modersohn-Becker’s pregnancy in her 1907 self-portrait. Darrieussecq writes that the only photograph of herself on the walls of her home, a portrait by Kate Barry, was taken when she was six months pregnant. ‘At the time, I often offered it to journalists when they asked me for an author photo. It was rejected every time. The answer was always the same: “We’d like a normal photo.”’[4]

Ah yes, the widely-known abnormality of a woman being pregnant.

With memory in mind, Eric Ormsby wrote:

‘Somehow I had assumed

That the past stood still, in perfected effigies of itself,

And that what we had once possessed remained our possession

Forever, and that at least the past, our past, our child-

Hood, waited, always available, at the touch of a nerve,

Did not deteriorate like the untended house of an

Aging mother, but stood in pristine perfection, as in

Our remembrance. I see that this isn’t so, that

Memory decays like the rest, is unstable in its essence,

Flits, occludes, is variable, sidesteps, bleeds away, eludes

All recovery; worse, is not what it seemed once, alters

Unfairly, is not the intact garden we remember but,

Instead, speeds away from us backward terrifically

Until when we pause to touch that sun-remembered

Wall the stones are friable, crack and sift down,

And we could cry at the fierceness of that velocity

If our astonished eyes had time.’[5]

In a Julia Blackburn book, I came across this: ‘I recently read an article about a retired accountant who uses a metal coat-hanger as a dowsing rod with which he can locate the exact position of the walls, windows and doorways of churches that fell down long ago and are now covered by grass and earth and forgetfulness. Sometimes he might sketch out an area where stones and bricks should be lying but when the archaeologists come to dig they find nothing there. This can be simply because he has made a mistake, but often it has turned out that he was locating a part of a building that had lain there concealed and undisturbed but was then dug up and removed many years ago. This phenomenon, of finding the memory of something that has vanished and left no trace of itself, is called by dowsers “remanence”.’[6]

Under ‘remanent’, my dictionary offers ‘remaining’ and, for the noun, ‘a remainder, a remnant’. My other dictionary, though, suggests for the adjective, ‘(of magnetism) remaining after the magnetizing field has been removed’.

The magnetizing field of memory; and the memory of ‘something that has vanished and left no trace of itself’. Elusive, allusive, illusive stuff. As for that photograph, the script will read: ‘Who’s this?’ ‘No idea. Looks vaguely familiar but. . . can’t quite place it.’

References

[1] Natalia Ginzburg, Family and Borghesia: Two Novellas, translated by Beryl Stockman (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1992), 68.

[2] Raphael Samuel, Theatres of Memory (London: Verso, 1996), 15.

[3] Patrick White, The Solid Mandala (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1969), 192.

[4] Marie Darrieussecq, Being Here: The Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker, translated by Penny Hueston (Melbourne, Australia: Text Publishing, 2017), 131.

[5] From ‘Childhood House’ by Eric Ormsby, in For a Modest God: New and Selected Poems (New York: Grove Press, 1997), 117. I believe I first saw this poem on the Anecdotal Evidence website years ago: http://evidenceanecdotal.blogspot.com/

[6] Julia Blackburn, The Emperor’s Last Island: A Journey to St Helena (London: Vintage, 1997), 176-177.