Reading Guy Davenport’s poems and translations, I paused on one of Sappho’s addresses to the goddess Aphrodite, liking the directness of its call, a sinewy compound of appeal and command:

Come out of Crete

And find me here,

Come to your grove,

Mellow apple trees

And holy altar

Where the sweet smoke

Of libanum is in

Your praise.

Where Leaf melody

In the apples

Is a crystal crash,

And the water is cold.

All roses and shadow,

This place, and sleep

Like dusk sifts down

From trembling leaves.

I paused even longer, I think, on this:

When death has laid you down among his own

And none remember you in all the years to be,

Know, grey among ghosts in that twilight world,

That, offered the roses of Pieria, you refused,

And wander forever in the dark lord Aida’s house

Reticent still, with the blind dead, unknown.[1]

(Guy Davenport, ‘in a somewhat silent, Shakerish mood and garb’, by Jonathan Williams, 1964. Taken from Portrait Photographs , Coracle Press, London, 1979)

Yes. I was reminded of the physical responses to authentic poetry that A. E. Housman famously described in a 1933 lecture. He cites a figure named Eliphaz (in the Book of Job), to whom he ascribes the sentence, ‘A spirit passed before my face: the hair of my flesh stood up.’ He mentions bristling skin, a shiver down the spine; and mentions one of Keats’s letters, in which the poet writes of Fanny Brawne, ‘everything that reminds me of her goes through me like a spear’. Housman is making the point, at some length, that to him poetry seems ‘more physical than intellectual.’[2] Many readers would describe their reactions, rather, as ‘both’, though probably granting that each might apply at different times and in different states of mind or knowing.

Davenport’s translation wears the simple title ‘Vale’, ‘farewell’. The poem is also included in his Seven Greeks, where he gives a little more space to Sappho than to any other of his chosen writers. His note to this poem explains that ‘Aida’ here is Hades and adds: ‘Written, seemingly, to a standoffish girl. Thomas Hardy translates this in a poem called Achtung.’[3]

Achtung? Hardy’s version of Sappho quotes The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám and Shakespeare as epigraphs and runs:

Dead shalt thou lie; and nought

Be told of thee and thought,

For thou hast plucked not of the Muses’ tree:

And even in Hades’ halls

Amidst thy fellow-thralls

No friendly shade thy shade shall company![4]

(Thomas Hardy: Dorset County Museum)

There is no poem called ‘Achtung’ in the index to Hardy’s Collected Poems. The title here is ‘Sapphic Fragment’, which seems reasonable. Two anthologies, The Oxford Book of Classical Verse, edited by Adrian Poole and Jeremy Maule, and Charles Tomlinson’s Oxford Book of Verse in English Translation, point me to more versions of the poem, but they too sternly name Hardy’s translation ‘Sapphic Fragment’. Ah, but there’s one more anthology to check: Confucius to Cummings, edited by Ezra Pound and Marcella Spann. Here’s Sappho and here’s that poem, called here, yes, ‘Achtung’.[5] The Pound connection is often useful when reading Davenport.

The Loeb edition offers: ‘But when you die you will lie there, and afterwards there will never be any recollection of you or any longing for you since you have no share in the roses of Pieria; unseen in the house of Hades also, flown from our midst, you will go to and fro among the shadowy corpses.’ The notes cite Stobaeus and Plutarch to the effect that the poem was addressed to ‘an uneducated woman’, ‘a wealthy woman’ or ‘an uncultured, ignorant woman’.[6]

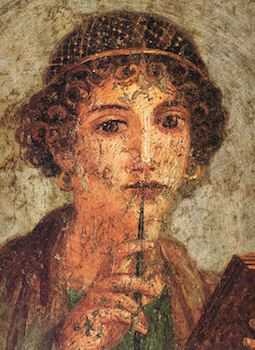

Still, ‘Written, seemingly, to a standoffish girl’, feels about right to me. ‘Her Aphrodite laughs’, Davenport writes of Sappho, adding, with characteristic sharpness, ‘Sexual frenzy was as respectable a passion to Sappho as rapacious selfishness to an American. Few societies have been as afraid of the body as ours, and in the West none has, within history, been as solicitous as the Greek of its beauty.’[7] And elsewhere, ‘Seems to me that Sappho was the poet of desire.’[8]

Desire, yes.

Percussion, salt and honey,

A quivering in the thighs;

He shakes me all over again,

Eros who cannot be thrown,

Who stalks on all fours like a beast.[9]

‘Vale’—or ‘Achtung’—sets the speaker, the poet who has accepted those Pierian roses, who has drunk deep of the Pierian spring, the fountain of the Muses in Thessaly, against that other, who has not embraced, either directly or through the person of the poet, intimate knowledge of the arts and sciences, who will pass into the shadows of Hades, unmourned and unremembered.

‘Pierian roses’ recalls that man Pound again: in Hugh Selwyn Mauberley, ‘The pianola “replaces” / Sappho’s barbitos’, while in Dr Johnson’s old haunts, Fleet Street has gone to the dogs; or, at least, to stallholders with socks to sell:

Beside this thoroughfare

The sale of half-hose has

Long since superseded the cultivation

Of Pierian roses.[10]

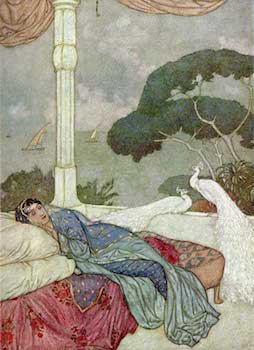

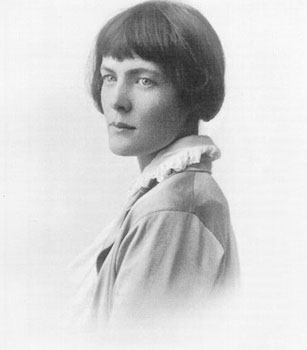

(H. D.)

Sappho’s art, Davenport, comments, ‘belongs to cultural springtimes and renaissance’—hints here of the Persephone theme which increasingly appears to occupy an entire continent in the world of modern literature—and she spoke ‘with Euclidean terseness and authority of the encounters of the loving heart, the infatuated eye’s engagement with flowing hair, suave bodies, moonlight on flowers.’ Her imagery ‘is as stark and patterned as the vase painting of her time’ – ‘Never has poetry been this clear and bright.’ And he quotes, by way of comparison, one of H. D.’s— Hilda Doolittle’s—‘conscious imitations’:

delicate the weave,

fair the thread:

clear the colours,

apple-leaf green,

ox-heart blood-red:

rare the texture,

woven from wild ram,

sea-bred horned sheep:

the stallion and his mare,

unbridled, with arrow pattern,

are worked on

the blue cloth.[11]

This is from a late H. D. poem ‘Fair the Thread’ (topped and tailed), though H. D. did produce translations, or imitations, of several of Sappho’s poems – or, rather, fragments. Sappho’s corpus consists almost entirely of fragments, which are often fleshed out by translators with guesswork and conjecture. They are also used—by poets—as taking-off points for longer, connected poems. One example is Swinburne, whose version of the fragment that Davenport called ‘Vale’ is embedded in the 300-plus lines of ‘Anactoria’, beginning there ‘Thee too the years shall cover’.[12] H. D. herself is another example, though a complicated one: the editor of her Collected Poems cites three early poems which are ‘masked as expansions of fragments of Sappho’, while one of her later critics, referring to those poems explicitly based on Sappho’s ‘fragments’, suggests that H. D.’s ‘textual play’ with Sappho ‘goes far beyond these’.[13]

Sappho’s concision and precision seem peculiarly fitted to excite the minds of the early modernist poets, particularly the Imagists; but then the fragmented state of her work, its blanks and inscrutabilities, bafflements and painstaking decipherments are also very appropriate to the story of modern literature.

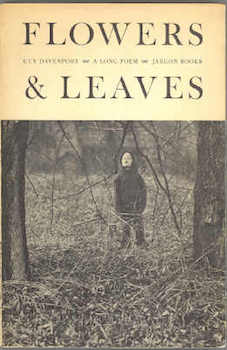

(Jacket of Davenport’s long poem, Flowers and Leaves, published by Jonathan Williams in 1966: Ralph Eugene Meatyard, ‘Untitled’, 1959. © The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard.)

One more Davenport-Sappho detail. Writing about his friend, the extraordinary photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Davenport remembered that, ‘Greek nor Latin had he, though he once figured out with a modern Greek dictionary that a lyric of Sappho (which he had set out to read as his first excursion into the classics) had something to do with a truck crossing a bridge.’[14]

The art of the possible. Why not?

References

[1] Guy Davenport, Thasos and Ohio: Poems and Translations, 1950-1980 (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1986), 32, 33.

[2] A Shropshire Lad and Other Poems: The Collected Poems of A. E. Housman, edited by Archie Burnett, with an introduction by Nick Laird (London: Penguin Books, 2010), 254-255: the whole lecture, ‘The Name and Nature of Poetry’, is reprinted here (231-256). The letter he refers to is to Charles Brown, 1 November 1820: Letters of John Keats, edited by Robert Gittings (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979), 397.

[3] Guy Davenport, Seven Greeks (New York: New Directions, 1995), 234 n.6. For his introduction, see 4-14 on Sappho, and for translations of her work, 69-116.

[4] Thomas Hardy, The Complete Poems, edited by James Gibson (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1976), 181.

[5] Confucius to Cummings: An Anthology of Poetry, edited by Ezra Pound and Marcella Spann (New York: New Directions, 1964), 18.

[6] Greek Lyric I: Sappho and Alcaeus, edited and translated by David A. Campbell (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1990), 99.

[7] Davenport, Seven Greeks, 9.

[8] W. C. Bamberger, editor, Guy Davenport and James Laughlin: Selected Letters (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2007), 163.

[9] Davenport, Seven Greeks, 87.

[10] Ezra Pound: Poems and Translations, edited by Richard Sieburth (New York: Library of America, 2003), 550, 556.

[11] Davenport, Seven Greeks, 5.

[12] Algernon Charles Swinburne, Poems and Ballads & Atalanta in Calydon, edited by Kenneth Haynes (London: Penguin Books, 2000), 52.

[13] H. D., Collected Poems 1912-1944, edited by Louis L. Martz (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1984), xiv; Eileen Gregory, H. D. and Hellenism: Classic Lines (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 148.

[14] Guy Davenport, ‘Ralph Eugene Meatyard’, The Geography of the Imagination (Boston: David R. Godine, 1997), 370.